Parts one and two of this three-part feature addressed what we have learned about the disease biology of COVID-19, and about pharmaceutical interventions to prevent and treat it. This third and final part will address the events that have elapsed since January and the current state of affairs.

We’ll wrap up this series by talking about what scientific developments, medical advances, and current events mean for what comes next.

Note: This article makes extensive use of our “levels” terminology, introduced in Pandemic scenario guide: a framework for thinking through what’s next for COVID-19. Here’s a brief summary of what the levels are and what they mean:

- Level 0: There are no active cases of COVID-19 in a given area. The default state of things all the way back before the pandemic began.

- Level 1: There are some active cases of COVID-19, but they are all contained. Unless this containment is broken or more cases arrive, reversion to Level 0 will follow shortly.

- Level 2: There is local transmission of COVID-19, but it is small. If all the cases were known, they could e.g. be separated into clusters with some degree of accuracy.

- Level 3: There is widespread local transmission, e.g. enough to thwart cluster tracking even with good effort, but the disease burden is low enough that medical facilities are not overwhelmed.

- Level 4: The local disease burden is large enough to overwhelm medical facilities but still small relative to the local population as a whole.

- Level 5: The local disease burden is large enough to make up a significant fraction of the local population. An epidemic of this scale is likely to result in a Big Burn, at least locally.

We have seen what a Level 4 COVID-19 epidemic looks like, and it sucks

The world watched events in Wuhan with a mixture of horror and surprise. It was our first look at what COVID-19 could do to a city. As I described it then:

People were banned from traveling or leaving their homes, the military was delivering food to houses, bodies were lying in the streets for hours before being collected, sick people were jumping off bridges to avoid going home and infecting their families, and every medical clinic was jammed while emergency clinics were set up in tents in parks. At night the empty city was suffused with a mixture of ambulance sirens and howls of distress from trapped residents on their balconies. The dead weren’t getting funerals, just cremation notices, and the crematoria were running around the clock.

While these scenes were completely new in February, the time since then has proven that there was nothing unique about Wuhan. Many cities around the world — including Milan, London, New York, Detroit, Tehran, Sao Paulo, and Bombay — have seen outbreaks that approach and in some cases rival Wuhan’s.

“Developed” status confers no immunity. New York City ran out of refrigerated trucks to store bodies, and prison labor was mobilized to dig mass graves.

Tropical climate confers no immunity. Bombay and Sao Paulo had searingly hot weather, and people still died.

Geography confers no immunity. We have now seen Level 4 clusters on four continents.

Having been hit before confers no immunity. The latest serostudies confirm that the bulk of the population has not been infected, even in the hardest hit areas. Wuhan, Milan, or New York could be hit again with a second wave worse than the first.

And areas which haven’t been through a Level 4 event are even further from natural herd immunity.

COVID-19 spread to every corner of the globe

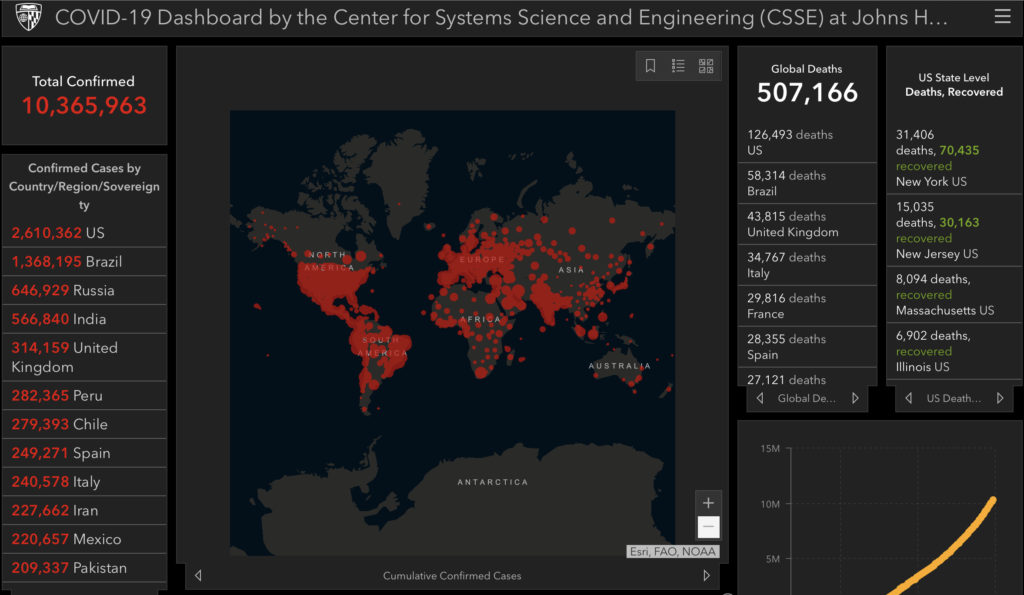

In the months since January, COVID-19 has gone completely global, with significant numbers of cases in almost every country in the world, and in almost every region of every country. It is everywhere.

In particular, nearly every country in the world has had, and most still have, local transmission of COVID-19 at or above what we call Level 3. That means they have community transmission on a sufficiently widespread basis that contact tracing, even with good effort, isn’t effective enough for true containment. But spread is not (yet) on a sufficient scale to overwhelm local medical facilities.

In addition, we haven’t beaten the epidemic on a global scale — or even contained it, or even stalled it — in any meaningful sense. New confirmed case and death numbers are still rising rapidly and have never stalled, other than for a brief period while growth was contained in China and was still ramping up slowly in other countries.

Daily new case numbers are the highest they have ever been, and they are rising rapidly. Daily death numbers are close to their highs. As of this writing, the world is suffering about 150,000 new confirmed cases of COVID-19 per day, and about five thousand deaths per day.

The world has seen widespread shortages of goods and services, including obvious pandemic-relevant items like masks, gloves, sanitizers, Tyvek suits, ventilators, and so on. This has been a huge drag on efforts to fight the pandemic, particularly in Level 4 clusters like Wuhan, Milan, and New York. There, hospitals have seen hundreds and thousands of COVID-19 cases. Meanwhile, they’re short-staffed and have inadequate PPE. Hospitals have turned into hothouses, with thousands of medical staff and non-COVID-19 patients infected.

In addition to this disheartening spread, many countries have been stricken with inadequate PCR testing capacity. That includes China in the early days of the pandemic and both Japan and the UK later in the Spring. The United States, nearly blind for lack of testing until April, only in June attained the minimum level public health experts had called for. Geographic spottiness has left many states still without adequate testing.

Local containment success controls local outcomes

The geographic distribution of COVID-19 has gone through three distinct phases:

Phase 1

In (approximately) January and February, the number of cases in various areas was driven primarily by their degree of proximity to Wuhan, and later to China as a whole, in the global contact network. E.g., Wuhan itself was hardest hit first, and this expanded to other parts of China and to places in the world with many connections to China, such as Vietnam, Korea, and Japan.

Phase 2

In (approximately) March and April, the hardest-hit places were those with the greatest degree of network centrality in the global contact network. As a result of this, developed countries with lots of air travel were hit hard. During this phase, the USA and Europe were very hard-hit, moving the center of the pandemic from Asia to the developed West.

Phase 3

From (approximately) May until now, the evolution of COVID-19 cases across different regions has been controlled mainly by the success of their local containment measures, not by the global contact networks.

What the ‘phase three’ dynamic means for us

The number of cases in each region now is largely independent of how many they had in even the recent past, or how many introgressions they get. Now, regional spread is mainly a consequence of the efficacy of each region’s internal control measures. When there are cases everywhere—as there are now—being a tiny little node in the global contact network is little protection, and neither is a low current number of confirmed infections. Exponential growth can swell a small number of cases to a huge number of cases very quickly.

Keep in mind that this is not a matter of how onerous restrictions are for the public, but how effective they are. This is why measures like testing, contact tracing, PPE, and sanitation are so important: they make a society more effective at containing the epidemic without asking more of the public and thus allow a society to keep R below 1 with less-intensive reductions in economic and social behavior.

As a result of this dynamic, the center of gravity of the pandemic has shifted decisively from Asia in January and February, to Europe and the United States in March and April, to the developing world and the United States now. As of this writing, the top ten countries by the five-day moving average of confirmed case numbers include the USA, the UK, and Spain, but also include Brazil, India, Mexico, Peru, Chile, Russia, and Pakistan.

Similarly, within the United States, the dynamic has shifted decisively from one group of states to another. While initially almost 90% of COVID-cases in the USA were located in “blue” states, now about three-quarters of new COVID-19 cases are located in “red” states. We are not concerned here with the politics of this transition; the example serves merely to point out that there has been a shift in the geographic distribution of the epidemic in the USA, and that it is driven by the effectiveness of control measures by governments, but mainly by people, in different places.

Containment is possible, and we have lots of examples

Along with the horror an uncontained outbreak can cause, and the spread of COVID-19 across the world, the last six months have seen another major development: the news that it is possible to arrest the spread of the disease.

As we predicted in March, a large number of countries have stalled the advance of their local epidemics and pushed them down in size, and a few have even pushed their case numbers to zero, achieving local eradication and returning themselves to Level 0, and consigning any additional cases of COVID-19 to those introduced by introgression.

These examples are not limited to a narrow category of circumstances. They embrace rich and poor countries, rural and urban areas, temperate and tropical climates, and a variety of global cultures.

Some countries have managed to prevent COVID-19 from significantly establishing itself. For example, Vietnam, home of some of the earliest cases, has had no COVID-19 deaths. Similarly threatened countries like Taiwan, Costa Rica, Australia, New Zealand, Thailand, and Cuba have so far kept their outbreaks from taking on large proportions, each suffering cumulatively under a hundred deaths.

But a larger number of countries, including those very hard hit, have managed to push their local epidemics down in size significantly. Switzerland, South Korea, Portugal, the Netherlands, Israel, Italy, Ireland, China, Germany, France, Finland, Denmark, the Czech Republic, Belgium, and Austria have all managed to slash their death rates tenfold. In addition, Canada, Hungary, Japan, Spain, Turkey, the UAE, and the UK have slashed their death rates at least fivefold. The United States, though the overall reduction in the moving average of deaths is less than fivefold due to ongoing surges in COVID-19 cases and deaths in a number of states, has seen a reduction of this magnitude in hotspots like the New York and Detroit metro areas.

Some countries have even attained local eradication, as in China, Australia, and New Zealand, so that these countries have been able to almost fully relax their internal controls and return to the introgression-focused posture many countries adopted at the beginning of the pandemic. More countries are likely to join them. And while both China and New Zealand have seen small outbreaks due to introgression, they so far have not seen prolonged periods of uncontrolled growth.

In some places, like China and Italy, these massive drawdowns in COVID-19 deaths have been accomplished with draconian lockdowns, which in Wuhan involved the doors to apartments being welded shut, sick people being forcibly quarantined, and wholesale bans on private travel. In many, they have involved widespread business closures and mandates on protective measures like masks and shelter-in-place orders.

But other countries have managed to contain their outbreaks without such aggressive measures. Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and Costa Rica have not ordered their citizens to shelter in place. It appears that in these cases, vigilance, testing, contact tracing, isolation, and widespread voluntary compliance with public health guidelines have been able to get the job done by itself, and without authoritarian mandates. Japan is hardly even testing.

In addition, while the pandemic has only been around for a few months, we see no indication that places that successfully lock down are necessarily fated to see large resurgences. While it has been common for either local spread or introgression to ignite new clusters in nearly every country which has attained control, as e.g. in China due to fish markets, Korea due to nightclubs, New Zealand due to introgression, and other examples, many countries have gone several months without returning to anything close to their peak levels, and there are very few examples (Israel is one) of countries which have seen large resurgences after attaining significant control.

That is, it has been proven that it’s possible for COVID-19 to be controlled for the kind of period of time which would allow therapies and vaccines to arrive. Whether the world as a whole is able to attain this level of success, with or without drastic measures like lockdowns, is less certain.

Economic crisis

The medical crisis of the pandemic has not happened in a vacuum. One of the primary control measures adopted in fighting it, on the part of both governments and the public, has been widespread and prolonged closure of travel, businesses, and public spaces. The result: waves of economic disruptions of various kinds sweeping across the world.

These economic shutdowns have caused sudden demand spikes, production disruptions, and distribution SNAFUs which have led to shortages in mundane items like webcams, toilet paper, pasta, beef, fitness supplies, bread yeast, and office furniture. In addition, classic panic buys like weapons, precious metals, storable food, and water filters have gone into shortages or seen huge demand spikes.

In contrast, demand for some everyday goods, like cars, office space, energy, restaurant food, movie tickets, and air travel, has completely collapsed (though some, like cars, are rebounding). We’ve seen spectacles like negative prices for oil futures, as well as a 95% reduction in air travel and a nearly 100% reduction in restaurant bookings. Other markets, like residential real estate, have plunged into stasis, selling activity plunging as prices remain largely frozen. Large corporations have almost all completely rescinded their earnings guidance. Global stock markets crashed, then rebounded, while measures of market turbulence remain near decadal highs. Interest rates have cratered for government bonds and mortgages but moved all over the map for personal and corporate lending.

Unemployment, poverty, and hunger have risen around the globe. In the United States, over 40 million have been cast into unemployment, about a quarter of the workforce, while unemployment rates have risen to levels unseen (even qualitatively) since the Great Depression of the 1930s. GDP has been estimated to be in danger of collapsing by as much as 50%. As a result of this, governments have committed themselves to trillions of dollars of emergency spending measures by both fiscal and monetary pathways.

Governments around the world have been disastrously incompetent

While the record of the pandemic presents examples of success, it also presents a litany of malfeasance and failure. Governments in countries around the world have racked up a shameful record of fecklessness, incompetence, and duplicity, with deadly results for their people.

Government officials have lied about the pandemic, claiming it wasn’t a real problem or would imminently disappear, and that their citizens didn’t need to take precautions. They have lied about statistics, presented them in misleading ways, or simply stopped reporting them. They have muzzled, or even fired, scientists and doctors in their governments who have tried to report the real story. In some cases, they’ve even prevented public health guidelines from being disseminated. They have relied on crackpot theories, prominently including ridiculous underestimates of CFRs and IFRs, but also including the use of Excel functions as epidemiological models, to support policy.

They have refused to take action to stop the pandemic, e.g. banning private COVID-19 testing while government-approved tests lag. In the case of the United States, the government refused to buy PPE or ventilators until they were already bulk ordering body bags. Others have banned the dissemination of information about outbreaks, e.g. which businesses and nursing homes have been affected, while others have required nursing homes to accept COVID-19 positive patients from local hospitals.

There has also been hopelessly confused messaging from governments to the public in many countries about the importance of masks, gloves, sanitation, and distancing in fighting the pandemic.

Governments around the world have also made a point of displaying their leaders’ refusal to participate in distancing measures and even held mass rallies without social distancing. Some of these leaders have even made a partisan issue out of PPE and other precautions, encouraging their supporters not to help protect each other. Legislators have even tracked COVID-19 into the halls of their state assemblies without telling other members of their legislatures. In more than one case, e.g. that of UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson and the president of Honduras, this kind of fecklessness has resulted in heads of state and other high officials coming down with the disease themselves.

At this point, countries whose governments have played these games are among the leaders in COVID-19 cases and deaths, including Brazil, the USA, India, and Mexico. Their failings are visited on the peoples they rule.

International collaboration has been similarly poor. Countries have squabbled over PPE and vaccines more often than cooperated, and international travel has been largely shut down. Significant aid from less-affected countries to those more affected has been largely absent, as leading developed countries have been unable to cope with their own outbreaks. The WHO itself has become a political football, taking unwarranted abuse from some governments but also inappropriately groveling to others by, e.g., not holding Taiwan up as the positive example it deserves to be, due largely to the tense political situation between the ROC and PRC.

Where are we now?

Before we proceed to synthesize all of this into a halting and approximate picture of the future, we’ll briefly denote the current situation.

Critical shortages of basic equipment have been mostly alleviated in developed countries. The USA now has enough masks for its medical staff (N95 and surgical masks) and its general population (surgical masks and cloth masks), and enough gloves, gowns, goggles, etc. The testing situation, while far from perfect, is not an acute crisis. There is not a national or global shortage of ventilators now, and production in initiatives like the GM/Ventec partnership is beginning to ramp significantly. In addition, while remdesivir is in shortage, dexamethasone is widely available.

By and large, every developed country except Sweden, along with a minority of developing countries, particularly in Asia, has controlled the pandemic and either avoided developing large outbreaks or pushed numbers down significantly from peak.

However, many developing countries are still seeing rapid growth, and the global case and death counts are still seeing rapid growth, with Brazil, India, Mexico, Peru, Chile, and Pakistan particularly hard hit and still exploding.

The United States is in a unique position. Parts of the country, like the Level 4 clusters in the New York and Detroit metro areas, look similar in pattern to Europe, with a sharp peak and a long decline, and no resurgence. Still, many other parts of the country show significant resurgences, like Florida and Oregon, or a largely uninterrupted increase, like Minnesota, Arizona, and Texas. This pattern is perhaps best visualized as a number of regional dynamics which operate almost as if they were separate countries bound in a union like the EU.

But if viewed holistically, the graph for the USA as a whole looks, on a death basis, like a peak and decline. Shallower and more gradual than that of other countries, but nevertheless a significant decline. The moving average of the US death rate has stalled and seen a sudden one-day jump due a reporting change in New Jersey, but so far has not seen a sustained increase.

New case numbers, which are slightly more confounded, have taken a long plateau and a small drop, and are currently headed upward sharply. As of this writing, they have almost doubled from their local bottom in less than three weeks, and have attained multiple progressive new highs in daily cases and the moving average. This has been accompanied by widespread and significant increases in the test positivity rate, i.e. it is not a testing artifact. The USA is seeing a large resurgence in COVID-19 cases, and is likely to see a similar increase in its death rate after a delay.

This is worrisome enough on an aggregate basis, but more worrisome still in the specific states which are seeing both large case numbers and rapid growth. As of this writing, states like Florida, Arizona, Oklahoma, South Carolina, and Texas are only weeks, even days away from being committed to a Level 4 event if they do not change course, while other states such as Idaho and Montana are seeing rapid growth in percentage terms even though their numbers are still small.

Despite this, the United States has for over a month been undertaking, and appears to still be committed to, what we refer to as a “YOLO reopening.” Every state is reopening significantly despite the fact that almost no states meet the federal reopening guidelines. States are issuing guidelines for reopening county by county and then shelving them, opening counties that do not meet guidelines. They’re proceeding through phases without meeting their declared criteria. Business are reopening without meeting legal standards or their own declared policies, and large segments of the US population are almost totally ditching hygiene and social-distancing norms. So far, even a significant national resurgence in COVID-19 cases in the United States has failed to dampen the national ardor for reopening.

The future: What’s going to happen and what to watch

So, what’s actually going to happen? Of our three scenarios (containment and eradication, sideways until therapies, and a global big burn), which are still in play? What is most likely to happen? How will we tell?

One thing that is important to remember, as grim as things are, is the finitude of the stakes. Although the number of lives in play is vast, it is finite and survivable. Even if a global Big Burn happens and IFRs are at the very top of current responsible estimates, this will not destroy humanity or our current civilization. Even if not only this happened, but also COVID-19 became a permanently endemic disease and never became less deadly, human civilization would not be destroyed by the virus.

But if we do not win the day, we could be in for a very bad decade. A global Big Burn continues to give every appearance of killing tens of millions of people, making it the largest mass casualty event since World War Two. Moreover, the worse the pandemic gets and the longer it lasts, the higher the likelihood of our pandemic-induced economic crisis turning from a downturn of typical length into a depression of decadal duration.

Scenario 1 is no more

Comparing our current situation to the one which existed in March, when we last assessed the State of the Pandemic, it is possible to say one thing definitively: Scenario One — containment and eradication — is gone. It’s not going to happen.

In March we had a limited number of examples of successful control of the pandemic in both developed and developing countries, enough to make a forecast that most or all developed countries would control the pandemic in the medium term. However, we were uncertain about what would happen in the developing world.

Now we know. While many developing countries have attained significant control, they have not done so with anything like the consistency of developed countries. It remains unclear if countries like Brazil and India, which are currently melting down, will control their pandemics in the near term or proceed directly to a big burn. But even if they can get things under control, other emerging hotspots in the developing world will continue flaring up for the foreseeable future.

At the same time, the timeline for vaccines and therapies to arrive is firming up in a relatively optimistic direction. There are now a large number of independent vaccine projects with diverse sources of risk which are already in the clinic and each independently intending to have scaled production and an efficacy readout within a year.

Combine these factors and the overall picture becomes clear. Even in an optimistic scenario, there just isn’t enough time to contain and eradicate. Right now, the world is at about 150,000 new cases of COVID-19 per day. Suppose that this number were arrested at 200,000 cases at the end of July and then the world maintained an R of .8 (averaged across the world) after that. At this rate, with the size of the pandemic falling threefold each month, it would nevertheless take a year to eradicate the pandemic, and by then therapies would have intervened to help us finish the job.

So, our best-case scenario is gone. Put it out of your head. We didn’t do a good enough job. If we succeed in stopping the pandemic short of a Big Burn, it will be therapies and vaccines, not NPIs by themselves, which enable it to happen. The world’s first line of pandemic defense, which saved us from SARS, MERS, Ebola, and other threats, has irreparably failed.

Do we get Scenario 2 or Scenario 3? It’s up to us

The world is in a very tense state. Beginning with the Wuhan outbreak, we have allowed the size of the pandemic to grow by six orders of magnitude in about eight months. If it grows by two more, tens of millions will die. We have proven that we can halt it, and the global biomedical community has vaccines and therapies coming in quantity beginning in as little as a few months and probably under a year.

Our global drama: will we hang on, or succumb? If we succumb, will the global travel shutdowns contain Level 5 clusters so that they remain local, sparing those countries which achieve durable local control, or will substantively the entire world be overwhelmed?

There is, by and large, little that can be done to significantly accelerate the development of therapies and vaccines that’s not already being done. Even human challenge trials, the ethically controversial clinical trial mode which could allow a near-immediate read on vaccine efficacy, would probably not significantly accelerate vaccine deployment. Current schedules have efficacy readouts arriving at the same time as, or before, scaled manufacturing.

Thus, with two scenarios left and the therapy ship already running at full steam (or, if you prefer, the therapy starship running at maximum warp), the future of the pandemic rests on this: Can we hang on long enough?

One factor speaks for optimism. Despite the opportunity, no country in the world has yet gone to Level 5 — where most of a local population has the disease. While many countries around the world have failed to prepare in advance or react promptly when push came to shove, when bodies piled up in the streets, and the nature of the crisis became indisputable, every affected country has so far found the mettle, in its government, its people, or both, to pull back from the brink. This includes China and Iran, so far the only two developing countries to host a Level 4 cluster.

In addition, of course, the nature of our plight has become ever clearer, as the picture of what therapies are likely to arrive, and when, has firmed up in recent months. That is, it should be clear to everyone that they only need to hang on for a relatively short period of time. And if, once vaccines begin to arrive, certain areas of the world are struggling with larger local outbreaks, we could direct the earliest supplies of a vaccine there to make an outsized difference even before they are available at a global scale. This could begin happening this year.

Both of these factors could be taken together to suggest that the most likely outcome at this point is that we succeed in stalling the epidemic until therapies and vaccines arrive, and attain Scenario 2.

Nevertheless, it would be foolish to make a firm prediction at this point. It could well be that developing countries simply get bowled over with a Big Burn in the next couple of months, and that is that. If so, developed countries and the Asian developing countries with a better record might be able to avoid sharing this fate in the near term, leading to a bifurcated “Fortress World” outcome. Or we might all be similarly overwhelmed. Unfortunately, we shall simply have to wait and see.

The unique situation of the United States is, other than rendering it unable to help other countries meaningfully, unlikely to remain a driver of the global dynamic, but it remains of special interest to our American readers. The situation here, despite the movement of case and death numbers first down, and then up, remains fundamentally as it was: the United States is fully capable of controlling its local COVID-19 epidemic, and has become more capable of doing so since March. But the country is still choosing whether to do this or not. If the United States experiences a Big Burn of COVID-19, it will be a straightforward, unalloyed failure on our part.

What to watch: Events, therapies, and cooperation

What should you keep your eye on to tell what’s actually going to happen? A couple of things will be important to watch:

What happens with case and death numbers in current hotspots in the developing world. So far, only two Level 4 situations have evolved in the developing world, and they have been suppressed (Wuhan) and blunted but not really controlled (Iran). However, now a dozen or more developing countries are facing emerging Level 4 clusters. If they are bowled over near term, that could be it, but if they cut themselves off at Level 4 the way the developed world consistently has, this would make it more reasonable to suspect that this may happen consistently.

How much trouble reopening countries have maintaining control. Right now, developed countries and the developing countries which have attained control are entering their second, third, even fourth month with their lower-level epidemics, and only a few (the USA, Israel) are seeing large resurgences. While it’s likely this record will continue, for the reasons we outlined in March, it’s less clear how much effort will be involved. If they settle into a stable equilibrium which keeps R less than 1 without much societal disruption, that’s a good sign. If they’re forced to use lockdowns and other blunt tools repeatedly, that will be a very bad omen.

Whether the global therapy development effort remains on track. When fall rolls around, will the AstraZeneca vaccine prove effective in human clinical trials and roll out at scale, or will it hit big snags which portend poorly for other vaccines? Will convalescent plasma and the Sorrento and Regeneron antibody cocktails hit the clinic in quantity, or not? Will the cavalry come when we think they are coming?

The extent of international cooperation. When therapies arrive, will they be deployed where they can make the most difference in controlling the pandemic overall, or will developed countries seek to relieve their economies first by dosing their populations before saving lives in developing countries? The decisions humans make about prioritizing access to these therapies can make a difference of months, perhaps quarters, in when they arrive in quantity at crisis points around the globe. The better we cooperate, the more likely we are to attain a good outcome together.

These are the things we’ll keep our eye on to influence our big-picture coverage.

After the pandemic

Regardless of what happens, the pandemic will be over in a couple years at most. What is less clear is how long the economic recovery will take. The recession induced by the pandemic is already very deep, but economists remain deeply divided over whether a sharp global recession like this can be recovered quickly once the pandemic which drove it is gone, in a mere few years, leaving a deep recession of approximately typical length. If not, pain could linger for a decade as in the Great Depression, leaving the global economy in a prolonged slump.

It is also unclear whether major economies will be pushed into deflationary depressions or significant inflation by the stimulus measures taken to fight the pandemic-driven economic crisis; the United States, for example, has already exploded its central bank balance sheet by nearly a factor of two and its debt to GDP ratio by several tens of percent.

There is also the grim possibility that COVID-19 may not be eradicated even when effective vaccines arrive, leaving humans to continue vaccinating and/or suffer COVID-19 to a limited extent for a very long time.

The pandemic crisis is not over, and neither is the global moment of the preparedness movement in the crisis. The array of possibilities continues to be brutally wide, and people’s need to prepare, to enable them to help themselves and others when things go poorly, is more critical than ever.

You are reporting the comment """ by on