Bare shelves in stores. Products out of stock. Skyrocketing prices. Basic services unable to function.

The Prepared has warned you about these predictable supply chain disruptions since early 2020 — but things have seemed to take a meaningful turn for the worse in recent weeks, to the point that even the optimists among experts are starting to worry about this dangerous snowball.

This post organizes all the recent news and analysis so you can understand more about what’s happening beyond the simple mainstream media headlines, along with tips on how you can prepare for the future.

Summary:

- Every type of product or service can be disrupted because the underlying problems (eg. no trucks/truckers or no water) can cause symptoms anywhere and everywhere.

- These disruptions are not evenly spread out in logical patterns, though. One dentist’s office might be open while another down the road is closed due to a lack of supplies and workers.

- Plan for the current weirdness to last through at least the end of 2022. If this winter is bad for COVID, you should expect disruptions to last into 2023.

- If you know you need something ahead of time, such as presents for the upcoming Christmas season, buy them as soon as you can.

- If you haven’t already prepared your household basics, such as food and water, do it. The chances of disruptions to even basic utilities is much higher than normal.

- The chief catalyst is of course COVID, but it’s no longer as simple as “beat covid = fix supply chain.”

- Natural disasters, geopolitical conflicts, and all the other major problems affecting the world matter, too — things snowball with each other into a complicated mess. For example, many cultures are now going through a kind of reflective inflection point, where workers are wondering if they even want to go back to the office.

How you can prepare for more supply chain woes

The reality is that you can only do so much to prepare for a collapse of the global supply chain. However, what you can do is make yourself more resilient and therefore buy yourself time to come up with more options, in the short term, medium term, and long term.

In short:

- Stock up on your essential needs: food, water, medicine, etc.

- Invest in longer-term necessities like generators and gasoline.

- Make contacts with local producers of food and other goods to localize your supply chain.

- Start producing your own food and goods as much as possible. Even if you can only do a little bit, the important thing is to practice for when times get tough.

Here’s the detailed plan for hardening your household against an increasingly shaky supply chain.

Short term supply chain preps

Here’s what you can do to prepare for the next few months of our supply chain rollercoaster:

- Go Christmas shopping now: Many industry experts are saying to go ahead and do your Christmas shopping or prepare for a quieter, less commercial Christmas.

- Prepare for Thanksgiving now: Some experts are also recommending that you go ahead and buy your Thanksgiving supplies now. Many Thanksgiving staples, like bread crumbs, boxed stuffing, canned cranberry sauce, and frozen turkeys, keep well.

- Stock your pantry: While you’re doing your early Thanksgiving shopping, stock up on shelf-stable foods that your family likes to eat. Rice and beans are a great staple, as are canned vegetables. See our supermarket survival pantry guide for more ideas.

- Store water: Invest in water storage containers and keep a supply of drinking water on hand. We’ve already seen shortages in liquid oxygen and chlorine used to treat water and we may see more shortages of water treatment chemicals.

- Take care of medical needs: Stock up on medical supplies and essential medications. An individual first-aid kit is a must, but consider your daily needs. If you’re taking prescriptions, talk to your doctor and insurance company about getting prescription medicines in bulk. If you depend on a medical device like a CPAP machine, make sure you have spare parts or maybe even an entire spare machine.

Medium term supply chain preps

Once your basic needs are met, broaden your scope to lesser needs that could be impacted by a broken supply chain:

- Invest in hard goods for the long term: If you have the cash on hand (don’t go into debt), go ahead and make practical purchases you’ve been considering. Do you have a generator? A freezer? Is your washing machine getting long in the tooth?

- Reduce waste in your home: It’s a tragedy to throw away food even in the best of times, much less when supplies are constrained. Learn how to preserve food and start a compost pile.

- Shop local: Start making connections with local producers to localize your supply chain. Make contact with a vegetable grower and maybe join a CSA. Make contact with local meat producers.

- Fuel up: Invest in some gas cans and store fuel at home for automobiles, generators, and power tools. And never leave your gas tank half empty.

Long term supply chain preps

Once you have a good stockpile of essentials, you’ve started dealing directly with small producers, and you’re preserving food and composting, you’re well on your way to a more resilient lifestyle.

- Expand your knowledge: Build up your preparedness library. Read the books, learn from them, and keep copies on hand for offline reference. A couple of recommended titles are The Resilient Farm and Homestead and Escape the City.

- Start producing: Buy seeds and learn how to garden. Gardening isn’t something you learn overnight and it’s definitely not something you want to learn under pressure. Get good at survival crops like potatoes, sweet potatoes, squash, and corn. Also trying to practice seed saving, which not only makes you more resilient but helps you create your own cultivars uniquely adapted to your environment.

- Consider livestock: Rabbits are one of the easiest animals to start with, as they’re cheap, easy to handle, require little infrastructure, efficiently convert feed to meat, and their manure is a fantastic fertilizer. Chickens are also a great choice for meat and eggs. Don’t jump directly to goats as your first livestock animal, as they’re more trouble than you may have heard.

When will the supply chain be back to normal?

The reality is that the supply chain won’t normalize until the COVID-19 pandemic ends, whether through eradication (increasingly unlikely), sufficient herd immunity through vaccines and prior infections, or everyone just deciding to ignore it and go back to normal as much as possible.

Here are three possible scenarios.

Best case scenario

Supply chains eventually even out on their own and we return to something resembling normal by the end of 2022. Many experts doubt that the supply chain will stabilize this year.

“Everyone is crossing their fingers that this works itself out by spring of 2022,” but there are no guarantees, Brittain Ladd, chief supply chain and marketing officer of Kuecker Pulse Integration, told Axios.

Takeshi Hashimoto, president of shipping company Mitsui OSK Lines, told Financial Times that he doesn’t expect normalization until the end of 2022. However, Hashimoto doesn’t think that will happen without governments intervening to “restore order.”

Average case scenario

Suppliers fail to get a grip on the supply chain but manage to trudge along despite problems. Things stay good enough that governments don’t feel the need to intervene. We experience a wonky but mostly sufficient supply chain for the better part of a decade.

Worst case scenario

Problems continue to cascade. Polarization in Washington prevents any meaningful legislation that would correct problems. Perhaps tensions around China and Taiwan heat up. Workers either don’t return to work or even more start to leave. Eventually, it becomes extremely difficult for manufacturers to produce basic parts to keep the supply chain turning. Things literally start falling apart and industrial society as we know it crashes unless some iron-fisted dictator claims power and centralizes production.

How government and business is responding

The Biden administration has released a report called When the Chips Are Down: Preventing and Addressing Supply Chain Disruptions that outlines the administration’s response to the supply chain issues:

- Voluntary surveys of producers to identify chokepoints

- Working with foreign governments to develop an early warning system for when factories are facing a COVID shutdown

- 100-day and 1-year reviews of the supply chain

- Encourage Congress to pass the CHIPS for America Act and establish the Critical Supply Chain Resiliency Program (CSCRP)

Frankly, it doesn’t amount to much, at least not yet, and big business has been forced to take matters into its own hands. Costco, Walmart, and Home Depot are all chartering their own cargo ships to ensure that their shelves stay stocked.

Examples of supply chain disruptions

You might be asking, “What’s in short supply? What’s hard to get?” The answer is pretty much everything. The trickier question is “when.” Some items, like automobiles and game consoles, are consistently in low supply while other items, like certain foods, come and go from shelves.

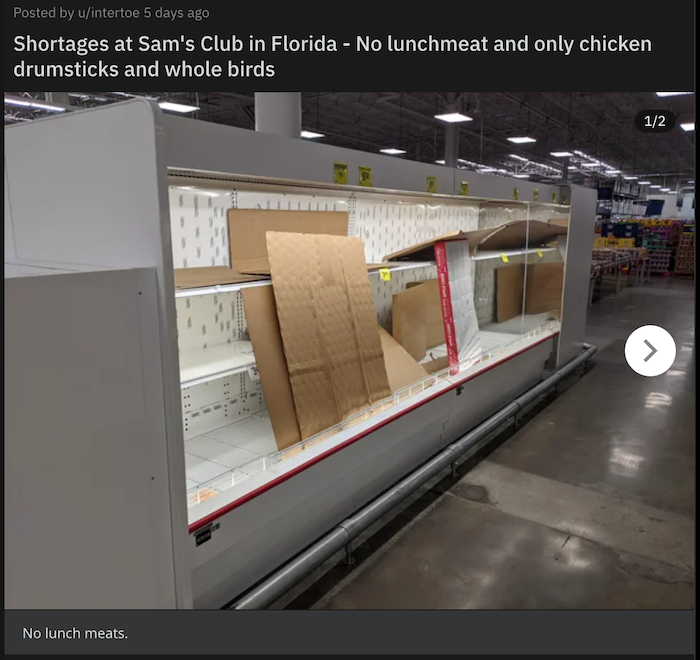

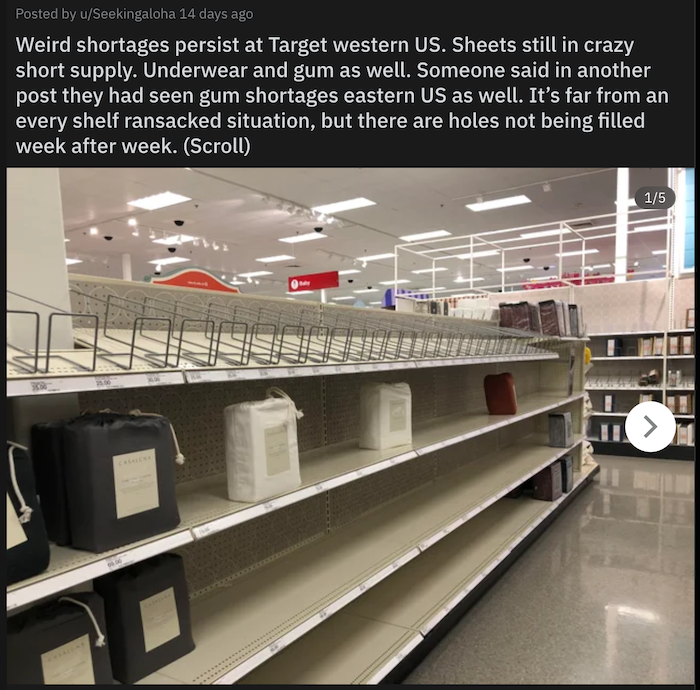

You may personally not have noticed any shortages, but that doesn’t mean they don’t exist. That’s due to the split screen effect, in which things may be fine in one place and a disaster in another. You may walk into one store and it be fully stocked, then walk into another down the road that looks like a tornado hit it.

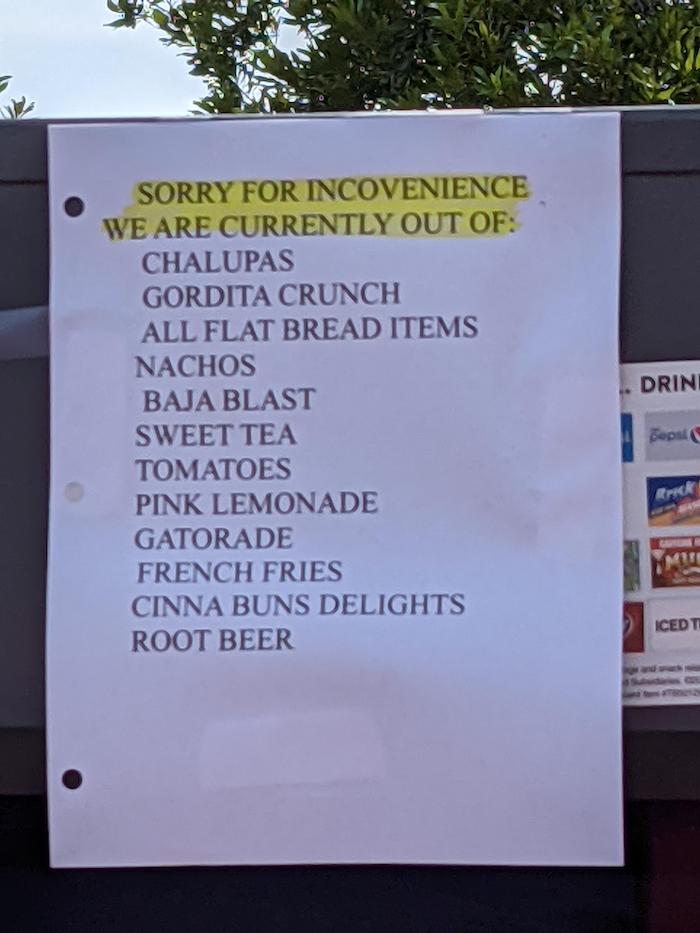

Examples of the supply chain disruptions happening all over the world:

- Food shortages in school cafeterias

- Costco is putting purchase limits on staples like toilet paper

- Prescription drug shortage

- A microchip shortage has shut down automobile production

- COVID treatment has led to a shortage of liquid oxygen used to treat municipal water

- A ransomware attack may cause a food shortage

- A chlorine shortage, another water treatment chemical

- Mechanics can’t get car parts

- Furniture is in short supply

- Toy companies are warning of holiday shortages

- Shortages of appliances and parts

- Nike can’t produce enough shoes

- KFC has stopped advertising chicken tenders because they can’t source enough

- Liquor shortages

- A shortage of Lunchables

- Britain is running out of gasoline

- Britain is also running out of CO2, used for many things in food production

- Britain is running out of pretty much everything else

Empty dairy and fresh meat shelves in Carrefour supermarket, Place Jordan, Brussels close to European Parliament. Not because of #Brexit @nealerichmond @simoncoveney @Nigel_Farage pic.twitter.com/UXCYybgpqt

— Hermann Kelly (@hermannkelly) September 28, 2021

Most of these aren’t world-ending events. Most of us could do without chicken tenders, liquor, and Lunchables. But what’s concerning is the breadth of the supply chain issues. It’s affecting everything from food, replacement parts, furniture, fuel, and even shoes, which paints a bleak picture of a global supply chain at its breaking point.

But don’t just take our word for it. Here’s what supply chain experts are telling the press.

“‘Everything’s broken’ is another way,” Dan Hearsch, a managing director at AlixPartners — a company that specializes in supply chain management, told The Atlantic.

Found out today: not only a national shortage of foley catheters but also Pleurovacs & BIS monitors.

Due to high demand for critically ill COVID patients.

Please get the vaccine. Even if you don’t have COVID, I’m losing the tools I need to take care of you in the ICU.

— Jennifer Hartwell, MD FACS (@traumamom4) September 25, 2021

Brittain Ladd of Kuecker Pulse Integration — which helps Amazon, CVS and Walgreens with their supply chains — told Axios, “What I hope consumers have already started to do is shop,” Ladd said. “The factories quickly sold out of their inventory and, frankly, everyone is still playing catch-up… Consumers really should understand that out of all the seasons they’ve been faced with, they really need to start this one as soon as possible.”

Takeshi Hashimoto, president of Mitsui OSK Lines — a shipping company that’s a member of one the world’s biggest shipping alliances — gave a dire warning to Financial Times: “If left entirely to the market economy, individual companies and individuals all doing their utmost to find the best solution for themselves will result in more and more turmoil and an out-of-control situation.”

Adam S. Posen, president of the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington, told The New York Times, “There is a genuine uncertainty here,” and added that normalcy might be a year or two away.

“There is no end in sight. Everybody should be assuming we are going to have an extended period of disruptions” Alan Holland, chief executive of Keelvar, a supply chain software company, told The New York Times.

“It’s definitely getting worse. It hasn’t bottomed out yet,” Tony Hague, who operates an automation company, told The New York Times.

Tony Costa, chief information officer at Bumble Bee Seafood, told CNBC that shipping costs have increased five-fold and that shipping times are taking up to four times as long as they used to. “Our typical truck shipment was between $4,000 and $5,000 before the pandemic. Now we’re seeing upwards of $19,000,” he said.

An open letter published by the International Chamber of Shipping warns of a “crumbling global supply chain”:

We are witnessing unprecedented disruptions and global delays and shortages on essential goods including electronics, food, fuel and medical supplies. Consumer demand is rising and the delays look set to worsen ahead of Christmas and continue into 2022.

The primary causes of supply chain disruption

In our guide to COVID-19, we warned: “Intermittent food supply disruptions, as supply chains struggle to adjust to ongoing and repeated plant closures, location-specific changes in restaurant demand, and the after-effects of widespread culling of flocks and herds.”

But let’s break down the specific ripple effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Panic buying

Perhaps the simplest cause of supply chain issues is panic buying. People fear shortages, so they buy more than normal, which causes shortages, thus creating a self-fulfilling prophecy. There have been recent reports of Americans panic buying toilet paper as they did in 2020, and panic buying of gasoline in the United Kingdom has exacerbated fuel shortages there.

In the big picture, panic buying alone isn’t breaking the system, but it has often been the main cause of empty shelves in the past.

However, what could be putting severe stress on the supply chain is that businesses are panic buying. Matt Stoller of the American Economic Liberties Project relayed this message from a home builder:

One home builder wrote me about shortages in his industry, noting that a lack of supplies “are, predictably creating further shortages, reminiscent of the toilet paper shortages in 2020: once someone finds black pipe or whatever, they buy way more than needed since they might not find it again. I’m as guilty as anyone; I have 50 stoves sitting in a storage unit since I’ll need them at some point. Meanwhile, a 54 unit project is in suspended animation while I wait for the Packaged Terminal Air Conditioners that won’t be in until next year.”

Factory shutdowns

COVID has led to factory shutdowns around the world, either due to government lockdowns or explosions in cases that sideline the workforce. These began at the start of the pandemic and are still going, especially in Asia where much of the world’s products are manufactured. Nike pinpoints its supply constraints to COVID-related factory shutdowns in Indonesia and Vietnam.

Indonesia and Vietnam were especially hard hit this summer, with COVID clusters forcing shutdowns of clothing, electronics, and wood product factories. Yeti, a popular producer of thermal mugs and coolers, has also been snagged by Vietnam’s COVID woes. Ankiti Bose, CEO of a major fashion supplier, recently said that Vietnam has “completely collapsed.”

China has fared better against COVID, but only thanks to its severe restrictions, which have often halted both factories and shipping ports.

And supply chain issues are also causing factory shutdowns, which we’ll explore later as cascading effects. Just one example: a COVID outbreak at a Malaysian supplier forced a Nissan plant in Tennessee to stop production.

Worker shortages

If you’ve ventured out lately, you’ve probably seen a slew of “help wanted” signs, maybe even advertising generous sign-on bonuses or other goodies. It’s no secret that businesses don’t have enough workers, but few seem to have a bead on the exact cause.

Uber and Lyft don’t have enough drivers. Desperate hotels are lavishing employees with expensive gifts. Having trouble receiving packages? Fedex is having to reroute over 600,000 packages per day due to a staffing shortage.

One answer could be simply that many of them have died. Nearly five million people around the world have died due to COVID-19. For instance, 12 school bus drivers have died in the Griffin-Spalding County School System in Georgia, causing a shortage of drivers. However, USA Today questions whether the deaths have had a major impact on the workforce since many were past working age.

Another often-cited cause has been the generous unemployment benefits offered by the federal government as part of its COVID relief effort. However, those ended earlier in September, and employers aren’t seeing prospective new hires flocking to the door.

Another cited cause was school closures. However, schools are now open across the country, and again, workers aren’t lining up to fill positions. JP Morgan recently reported that only half of those who lost their jobs due to COVID-19 have returned to work.

Economists have proposed a few reasons for the worker shortage:

- A broken hiring system: Many employers rely on AI-driven systems to filter candidates, which tosses out good candidates with the bad. Employers want employees they don’t have to train and who have certain qualifications, but overlook those who could be easily trained or have work experience over education. Employers were able to be picky in the recovery from the Great Recession and they are being slow to adapt to the new reality, which is why you may have trouble finding a job even if businesses are seemingly desperate for work.

- Uncertainty over the pandemic: Many workers just don’t want to catch COVID. Or they don’t know when their school may shut down or a child or other family member may be forced into quarantine and so they don’t want to make big commitments.

- Workers are fed up: COVID-related dangers and job insecurity have caused workers to grow fed up with grueling, low-paying jobs. For example, daycare workers are abandoning childcare to work at higher-paying chains like Dunkin Donuts and Walmart. Workers are quitting in droves, leading to a phenomenon known as The Great Resignation.

- The lack of daycare workers: As people leave childcare, it creates a second-order effect when parents can’t find care for their younger children.

Whatever the causes, it’s now workers, not employers who have the power in the relationship. Many employees are now perfectly comfortable ghosting employers to pursue better opportunities. Some economists also speculate that many are living off money they saved from stimulus checks and unemployment benefits.

In any case, until things change, the lack of employees means fewer people to produce goods and fewer people to stock shelves. Even those who have an indirect impact on the supply chain, like daycare workers, make a big difference. Employers either need to adapt or keep hoping that eventually the savings runs out and people flock back to work.

Another factor to keep an eye on is COVID vaccine mandates. President Biden recently vowed to enact new OSHA regulations to make COVID vaccines mandatory for most jobs in the United States. That has yet to come to fruition, but we’re seeing the effects of vaccine mandates in states and cities. New York State is bringing in the National Guard to fill in the gaps caused by nurses refusing the vaccine mandate. Dozens of state troopers in Massachusetts have resigned over the vaccine mandate. 175 healthcare workers were fired in North Carolina due to refusing the vaccine mandate. It’s hard to say what effect mandates will have on the overall workforce, but even a small amount can only exacerbate the existing worker shortage.

Travel restrictions

Incongruent travel restrictions have hampered transport workers, and they’re getting fed up. In an open letter, the International Chamber of Shipping (ICS) said:

We have all continued to keep global trade flowing throughout the pandemic, but it has taken a human toll. At the peak of the crew change crisis 400,000 seafarers were unable to leave their ships, with some seafarers working for as long as 18 months over their initial contracts. Flights have been restricted and aviation workers have faced the inconsistency of border, travel, restrictions, and vaccine restrictions/requirements. Additional and systemic stopping at road borders has meant truck drivers have been forced to wait, sometimes weeks, before being able to complete their journeys and return home.

The ICS represents 65 million transport workers worldwide. Workers told CNN that they’ve been subjected to weeks of quarantines, months at sea without shore leave, and repeated vaccinations — as many as six doses — due to conflicting standards between countries. In 2020, some 400,000 seafarers worked up to 18 straight months due to a lack of leave.

Strict testing requirements can also be onerous, forcing transport workers to wait sometimes days in the cold to get tested for COVID. One crew had to endure 10 COVID tests in a week before docking in Singapore for repairs.

The ICS says the abuse is causing transport workers to quit entirely, making the supply chain situation even worse.

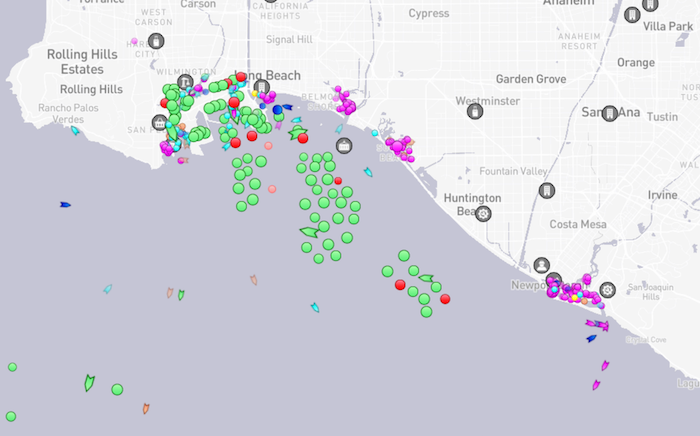

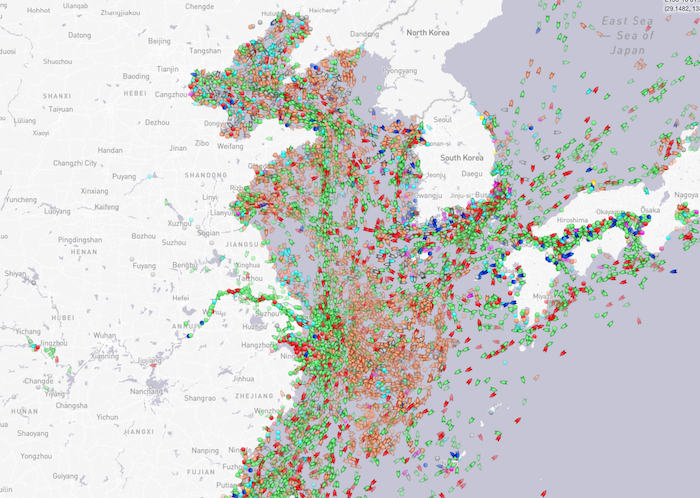

Shipping congestion

There is a record backlog of container ships at major ports. California has so far had up to 60 ships queued up and New York has had 20. Things are no better in Europe. This is a growing problem — the California backlog was 33 ships in July and has nearly doubled since.

Things aren’t much better in China.

An increase in demand for imports has largely been to blame, but like every other industry, docks are facing a worker shortage, and the price of shipping containers has skyrocketed. The Suez Canal blockage earlier this year also probably hasn’t helped.

As the backlog grows, that means goods are taking longer and longer to reach shelves. With so much of the western world having offshored its manufacturing overseas, that’s a big supply chain threat.

Extreme weather

Adding to the other problems are extreme weather conditions wreaking havoc on crops and shipping.

The world’s supply of coffee is shrinking thanks to droughts in Brazil and heavy rains in Colombia. Brazil produced 40% less coffee this year than last year.

Typhoons in China have put even more pressure on the supply chain, as ports have been forced to close, leading to more container pileup and higher shipping costs.

Here in the United States, Hurricane Ida disrupted shipping lanes, leading to higher barge shipping costs. Ida has also impacted the chemical and plastics industries.

“It’s going to have a significant impact,” she said. “Companies that make coatings, paint, shingles or treated lumber — a lot of these companies are going to have to slow down,” Megan Gluth-Bohan, the chief executive of TRInternational, told the New York Times.

In addition, Ida wrecked more than 250,000 cars, which could lead to even higher prices on new and used vehicles.

Electrical supply issues

A recent, unexpected, and concerning development is a lack of power. Chinese suppliers for Apple and Tesla have had to suspend production due to insufficient electricity. China is now asking food producers to shut down.

CHINA ENERGY CRUNCH: The electricity shortages in China are worsening, and widening geographically. It's getting so bad Beijing is now asking some food processors (like soybean crushing plants) to shut down | #OATT #China #EnergyCrunch with @cangsizhi More on @TheTerminal

— Javier Blas (@JavierBlas) September 24, 2021

Chinese government officials are mandating power cuts to meet energy and emission targets. China is also facing a severe coal shortage. China also recently banned cryptocurrencies, possibly due to the high energy consumption of crypto “mining.”

China isn’t the only place facing an electrical short. Electricity prices are skyrocketing in Europe due to a shortage of natural gas from Russia and Norway. A fire at a natural gas plant in Siberia cut supply. Europe usually offsets natural gas supply issues with coal, but Chinese demand for coal has made that impractical. Also at play are carbon permits, which constrain energy supply. On top of all that, Europe is also facing a shortage of wind to power wind turbines.

The United States may feel those supply constraints this winter. Propane inventories are 21% below the five-year average, which is almost unheard of.

Industry consolidation

Another key aspect of supply chain fragility is that a handful of companies control much of it. The White House recently pointed out that four large conglomerates control the majority of the market in beef, pork, and poultry. Even as meat prices skyrocket, the farmers are making less than ever. Two industrial gas giants merged in 2017, and now we’re seeing an oxygen shortage.

As consolidation increases and there are fewer and fewer companies making things, those companies can exert more control and thus create more bottlenecks. A shortage of proprietary plastic bags slowed down vaccine production, and machines that can’t be easily repaired also lead to bottlenecks.

Take Apple as an example. You need a proprietary charging cable to charge an iPhone, and if it breaks you’re practically forced to take it to the Apple Store. Except instead of an iPhone, it’s a John Deere tractor that’s broken down at harvest time, you need a proprietary part that John Deere can’t make enough of, and you have to wait for a John Deere technician because they’ve made the machine impossible for you to service.

Double trouble: Cascading supply chain disruptions

Even more concerning is that these issues are colliding to exacerbate each other while also creating worse supply chain issues down the line. For instance, the natural gas shortage is shutting down fertilizer plants, which will mean less food on store shelves. Two areas of particular concern are in microchips and trucking, and both play into each other.

It seems like every product has a microchip in it these days, and most of the world’s chips are produced in China and Taiwan. A variety of factors have been blamed for a shortage of chip production, including:

- COVID outbreaks and subsequent lockdowns, which are ongoing. In June, King Yuan Electronics Co. in Taiwan shut down its main factories due to a COVID outbreak.

- This year, Taiwan experienced its worst drought in 50 years. Manufacturers require great deals of clean water to produce chips.

- The trade war between China and the United States.

The problem has also been exacerbated by the high demand of processors for mining cryptocurrency and the demand for new game consoles from Microsoft and Sony.

But where the chip shortage has had the most impact is in automobile manufacturing, and many automakers have been forced to cut features or cease production entirely:

- GM forced to halt production

- Ford cut F-150 production

- Nissan closed a Tennessee factory for two weeks

- Toyota has been forced to slash production and close factories in Thailand

The chip shortage is expected to cost automakers $210 billion this year alone. It’s also caused a surge in used car prices.

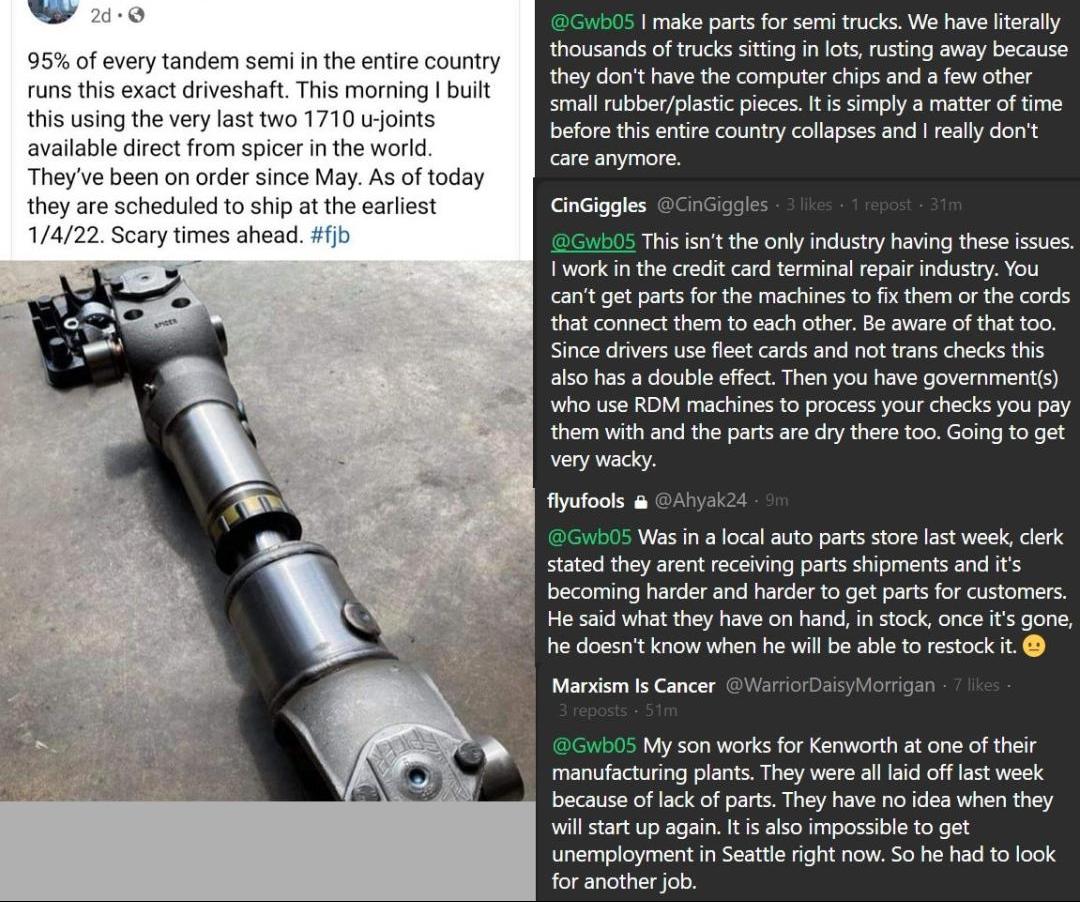

But even worse is that the chip shortage is halting output of semi-trucks, which power much of the supply chain. Not only are new semi-trucks in short supply, but there’s also a shortage of parts to repair trucks already on the road.

It isn’t just chips constraining supplies of semi-trucks and replacement parts. There’s a rubber shortage due to flooding and the ongoing lumber shortage is making it hard to produce trailer floors. Suppliers have been forced to cannibalize wrecked vehicles for parts.

Caption: Anecdotes abound about part shortages.

Not only are there not enough trucks or parts to replace them, but there also aren’t enough drivers, and that’s already leading to restaurant food shortages. “The driver situation is about as bad as I’ve ever seen in my career,” Eric Fuller, CEO of U.S. Xpress told Yahoo Finance. That’s despite offering pay increases of up to 35%. Fuller isn’t optimistic that the level of drivers will return to pre-pandemic levels.

We’re potentially looking at a series of cascading supply chain failures. If logistics companies can’t get enough trucks, can’t keep trucks running, and can’t keep enough drivers on the roads, it will lead to even more shortages on store shelves. Meanwhile, cargo ships will continue to pile up because there aren’t enough trucks to offload the contents.

To see a visual of how dispersed and fragile the supply chain is, check out the Wall Street Journal’s breakdown of what it takes to build a hot tub and how production has been stymied by the pandemic, the winter storm in Texas, port shutdowns, and trucking shortages.

You are reporting the comment """ by on