The one question The Prepared has been asked the most over the last few months is how to prepare for supply chain disruptions. If you keep up with our twice-weekly news roundups, you’re aware of supply chain bottlenecks, rising meat prices, bare shelves, and the worldwide chip shortage that has screwed up everything from game consoles to automobiles. There are also many readers concerned about pandemic measures like lockdowns and vaccine passports that could limit travel or shopping.

More: The state of the supply chain in early 2021

Although the trend of people wanting to localize their supply chains was already growing before Covid, these recent disruptions have really ramped up the community’s desire. Localizing your supply chain simply means getting the things you need from the people around you, rather than waiting for it to ship in from places like China.

More: COVID-19 and the Delta variant: what you need to know in August 2021

Direct relationships with producers can often be both more reliable and cheaper than going to the store. For example, while beef and lumber prices have skyrocketed, prices from my local producers have remained about the same and are often well under national prices.

It pays to make these connections before you need them. During the initial stages of the pandemic, for example, our local meat vendor was overwhelmed with orders — but they made sure we got our meat because we had been customers for so long.

Summary:

- The most important thing you can do to localize your supply chain is to become a customer of your local farmers. It’ll take some legwork, but you can easily find local sources of meat, vegetables, dairy products, and honey.

- Make it a priority to learn how to preserve food so you’re less dependent on the global supply chain in the winter.

- Connect with local tradesmen and crafters like welders, blacksmiths, and basketmakers so you can get things repaired and source locally made products.

- Learn how to render lard and tallow (from your meat supplier) so you have a local source of grease to cook food and lubricate tools.

- If you live near a lot of trees, consider switching to wood heat so you have local heating fuel.

- Call or visit local sawmills to find local sources of lumber. You can often find better deals than the big box stores.

- Document the trees and plants in your area and learn what they’re good for.

- Invest in quality, manual hand tools that don’t require electricity or fuel, which makes you less dependent on the global supply chain.

- Keep some of your money in a local bank or credit union that isn’t owned by a big national chain.

- Eventually, use your newfound connections to become a producer yourself.

Buy directly from farmers

If you take absolutely nothing else from this post, do this: make connections with people who produce or distribute local food.

That could be a neighbor who grows a bigger garden than they can handle. Your best bet is with the farmers in your area, and there’s probably more of them than you think. But farmers don’t tend to be great marketers, so making contact can take some legwork.

Ironically, this may be easier if you live in a city with a large farmer’s market. Many rural farmers sell in the city since they can get better prices. An easy way to make connections is to visit a farmer’s market, meet the people there, and collect some business cards. You could even start a book or spreadsheet of nearby producers.

There are a number of small retailers around the country that focus on selling products from local farms, like Demeter’s Common in Lebanon, TN and Howard’s Harvest Market in Scottsville, KY. These can be great hubs for finding producers — just look on the labels and note where the food comes from.

Many small farmers and market gardeners offer a CSA, short for Community Supported Agriculture. They’re all a little different, but the gist is you pay a certain amount up front or commit to a regular payment, and you get a box of vegetables every week during the growing season. Some have a buffet-type system where you can go down a line picking the vegetables you want, and some even offer meat.

If you have an Amish or Old Order Mennonite community near you, they’re also great resources. Many people in those communities grow food to sell and run their own stores.

Finding those communities is the easy part, while finding vendors in them is trickier since they don’t usually have Google Maps listings or phones. Sometimes you can find user-made maps of these areas online, but your best bet is talking to people in those communities and driving around.

A country drive can reveal all sorts of resources you may not find otherwise. Some people sell things like eggs and advertise only with a sign in their front lawn.

Here’s a real-world example: we visited a Mennonite vegetable market where we bought some bacon. We looked at the label and decided to find the source, which led us to the Downing Cattle Company. We bought some meat there and they led us to Kenny’s Farmhouse Cheese, and on the way we discovered a few more places. Once you start getting plugged into these networks, it gets easier to make more connections.

If you use Facebook, look up and “like” small farms in your area. You can often trade with them or be led to other sources. Many small farms do business “under the table” for verboten products like raw milk (for your pets, of course). Some farmers offer a herdshare, where you pay a certain amount and get access to milk, meat, eggs, etc. Sometimes herd shares are exempt from the usual rules surrounding raw milk. (If you like the idea of a local milk source but raw milk makes you nervous, you can pasteurize it yourself.)

With meat prices skyrocketing, you might consider buying a herdshare or a half or whole cow or pig. Expect to spend a lot up front, but when you do the math you’ll probably find that it’s a lot cheaper per pound than the store. Before you even consider this, you’ll want a large freezer, because just half a cow will fill a freezer. (Make sure to get a freezer with a lock to discourage petty thieves. It also pays to invest in a generator.)

Here’s how that works:

- Talk to the farmer and agree upon a price.

- The farmer will send the animal to a meat processor for slaughtering and butchering.

- You call the meat processor and tell them what cuts you’d like. They might give you something called a “cut sheet” where you can list what all cuts you want, which is totally overwhelming. You can usually talk to the processor to get recommendations and they’ll probably have a standard cut list that you can work from, which makes things a lot easier. For instance, do you want t-bones or do you want strips and filet mignon? Do you want the liver? And so on.

- The processor packages your meat and you arrange to pick it up.

- You either swing by the farm and pay directly or leave payment with the processor.

- Pick up your meat and put it in your freezer.

You can easily fit a half beef in the back of an SUV or the trunk of a car. If you’re driving a long distance, you may want to bring coolers. If it’s a short drive, crank up the air conditioner.

A half beef will give you a lot to work with. Expect several steaks, lots of ground beef, a few roasts, and some things you may have less experience with, like liver, beef ribs, and briskets. Just like with the CSA, you may have to get a little creative to get your money’s worth.

My favorite thing about buying our meat locally is that they vacuum seal the meat so it freezes well. No crappy styrofoam trays and shrink wrap here.

Learn to preserve seasonal excess

Because localizing your food supply means you’re no longer depending on a massive and destructive international supply to bring you a single banana from the other side of the planet at any time of the year, you’ll start to be more aware of growing seasons.

Unless you live in a particularly warm area, tomatoes are only available in the summer, for example. If you belong to a CSA or are plugged into a farm network, you can often buy a bulk of certain vegetables, like tomatoes, for cheap because they spoil fast and often come in at once.

So after you build a good food network, check out the guide to food preservation to get started and be able to take advantage of those opportunities and eat well the whole winter.

Make connections with local tradesmen and crafters

Less important than food, but still a good resource, is being hooked into local crafters. This will probably happen naturally as you acquire local food sources, since many farms also offer various goods and services to pay the bills.

You can visit a community craft fair and start a pretty good collection of contact for basketmakers, weavers, soap makers, and so on. They’re also good places to meet beekeepers, since many of them sell beeswax and honey-based products (another local food source!)

Two crafters you want to have on hand are a welder and a blacksmith. You probably won’t find a welder at a craft fair, but many farmers (like the ones you buy food from) are decent welders or you may have a small welding shop in your town. My neighbor is constantly taking equipment to a welder for repair, and a welding friend fixed the scythe I broke. If the supply chain is a mess, knowing someone who can repair your broken things with few inputs is a good thing to have.

Blacksmiths can make all sorts of useful tools like hooks, knives, screwdrivers, etc. A nearby blacksmith forged this amazing dragon hacksaw. There are a number of blacksmith organizations and clubs around the country — check for one in your state.

Locally source your grease

This is sort of an odd suggestion, but you probably use grease for stuff all the time (eg. cooking or keeping rust off tools), and once you have local connections for meat and honey, it’s right there for extracting.

Two sources of animal fat are lard, which is rendered pig fat, and tallow, which is rendered cow fat. Lard is liquid at room temperature and tallow is solid. Tallow is especially useful; old-time tradesmen would rub it on their tools to keep them from rusting. And you can make edible candles from it.

Rendering lard and tallow is easy if you have a crockpot. Dice up your animal fat, toss it in the crockpot on low with the lid off. Stir it every so often, and once the fat bits start turning brown, kill the heat, scoop out the fat bits, and carefully pour the liquid fat into a heat-resistant container, like a mason jar. Set it aside to cool, and then put on a lid and store it in the fridge.

Beeswax is another useful material to have around because it has many uses. I like to rub it on things I’ve forged as they’re cooling to rustproof them.

Switch to wood heat

This is a big investment and maybe not practical where you live, but if you have a wood stove, even as a backup, you have a heating fuel you can source locally. Chances are, kerosene and propane aren’t produced within walking distance of your house — but unless you live in a desert, I bet there are a great deal of trees.

Of course, wood heat comes with a huge set of drawbacks:

- It’s dangerous, in terms of burns, fires, and carbon monoxide

- Many insurance companies won’t insure a home with a wood stove

- Wood stoves are expensive to install

- You have to split and stack wood, plus have a safe place to keep it

- Wood heat isn’t as easy to control as the alternatives

But… firewood is easy to source, and it’s often available when nothing else is. If you investigate this route, make sure to hire a pro who can set things up correctly so you don’t burn your house down or kill your family with carbon monoxide poisoning.

Visit your local lumber mill

One of the great background stories of the past year was the skyrocketing price of lumber. At least, if you bought it in a big box store. The lumber mills around here sold their boards for about the same price they always had. A nearby mill has a pile of free scraps. A friend built raised beds for free this past spring by digging through the scrap pile.

Lumber mills all work a little differently. Some won’t sell to individuals. Some only sell furniture-grade hardwoods. It pays to call ahead and ask.

Another resource: Wood-Mizer sells affordable mills to individuals. Affordable, but still expensive. To help offset the price, Wood-Mizer lets its customers advertise their services on their website. If you can’t find a sawmill that will work with you, someone on the Wood-Mizer site might be more than happy to help you out.

Working with lumber mill lumber is different from what you get at a big-box store or lumber yard. The inventory tends to get wet, so it needs to be dried for construction projects, and it tends to be rougher than commercial lumber.

Be aware of local building codes. Most places require lumber be stamped, and lumber mill lumber is usually not. You can pay a company to inspect and stamp it for you, or your locale might have special exceptions for local lumber. In Tennessee, we have the Tennessee Native Species Lumber Act which lets sawmills and property owners certify their own lumber.

Learn about your local flora

You may be surrounded by natural resources and not even know it. For instance, I have a crabapple tree in my yard. Some friends recently picked it and shared some applesauce with me. I picked some to make apple cider vinegar, which can be used for cooking, cleaning, and making garden amendments.

We’ve talked about the uses of plantain and wild garlic in the past, as well as sources of natural toilet paper. Your surrounding area could be full of foods, medicines, cordage, and fuel. Check out the list of great survival books for field guides that can help you identify useful plants.

Invest in resilient hand tools

The tools you buy probably aren’t local, unless you get your blacksmith to make them all for you. But what you can do is invest in well-made tools that will work without any external inputs. It’s less about localizing your supply chain and more about making you less dependent on the supply chain. For every power tool I have, I try to have a manual equivalent. Some examples:

- Angle grinder: files, hacksaw, hot cut hardy

- Chainsaw: axe

- Circular saw: hand saw

- Lawnmower: scythe

- Planer: hand plane

- Power drill: bit and brace

- Tiller: broadfork

- Washing machine: washboard

I just bought a washboard so I can handwash clothes/linens in the bathtub. My 3-year old washing machine is under warranty, but it is never going to be repaired. Claims Department no longer responds. I can buy a new one, but it will take months to deliver. Welcome to the future.

— Laura Miers (@LauraMiers) September 15, 2021

You can buy a lot of these tools at yard sales and estate sales. I have to show up early, because the local Mennonites are after them too. Don’t be afraid of a little rust (a vinegar soak will remove it), but beware of pitting in the metal, which compromises its integrity.

For new, high-quality garden tools, I like Easy Digging. I bought my broadfork and pointed hoe from them, and they are both well-made and resilient tools that can withstand a lot of abuse. Lehman’s, a retailer that caters to the Amish and other plain people, is another good source for off-grid tools.

Keep money in a local bank

Many of us now use online banks, have money deposited directly into those accounts, and withdraw the cash we need from an ATM. We don’t interact with anyone at the bank, much less know anyone there.

We use an online bank as well, but we also keep some of our money with a local bank, and I would encourage you to do the same. I don’t mean a local branch of some big mega bank, but a local bank or credit union. There are a few reasons for this:

- The machinery of big banks often ban people unceremoniously, without warning, leaving them unable to get their funds. Banks do this because they don’t like the politics of a customer or because the customer triggers some automated warning system, like what happened to this teenage boy at Chase in 2013. I have the home number of my bank’s president.

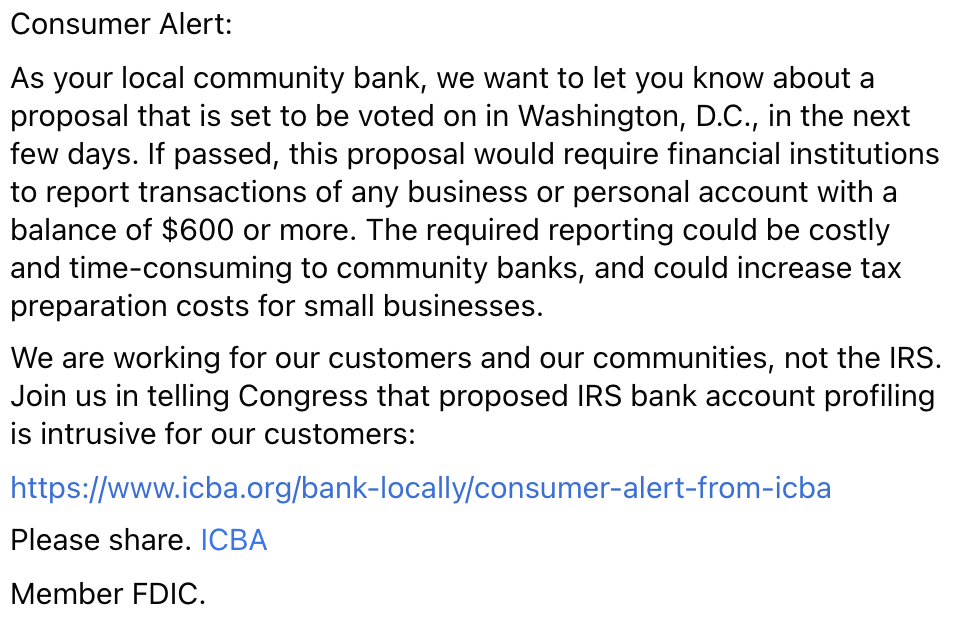

- While my bank is as beholden to federal laws as any other bank, I feel like I have an advocate with my local bank. For example, they posted this notice on their Facebook page about a proposed rule that would notify the government of any transaction of $600 or more.

- Your money is within a short distance. If there’s an Internet outage, you can still go to the bank and get cash.

- A local bank can offer services like safety deposit boxes to store important documents. (I don’t recommend keeping valuables in them because the government can seize them.)

- You can get other perks as well. Many local businesses offer a discount if you have an account at the local bank. I had my PPP loan forgiven before many people got theirs approved and a loan officer spent hours on a Saturday to help us get a mortgage.

Start producing

One of the best long term preps you can make is to start producing for yourself. And once you have connections with local producers, that becomes a lot easier. You build a support network that can give you advice or a helping hand when you need it.

For example, the couple we buy milk from also raises rabbits. I had wanted to get into rabbits myself, but didn’t know where to start. When they upgraded their hutch, they let me have their old hutch, taught me how to process rabbits, and sold me a few for a song.

You’ll find a lot of homesteaders are more than happy to help you become more self-reliant because when the stuff hits the fan, that’s one less person coming to their door. And once you have a good network established, you’ll find opportunities that you may not have even know existed.

You are reporting the comment """ by on