We recently shared research about prepper demographics from Dr. Chris Ellis, a US Army Strategic Planning and Policy Program Fellow working with Cornell University. To clear up confusion, Dr. Ellis created an academic definition of what’s commonly called a prepper: a Resilient Citizen is someone who can handle at least a 31-day emergency or self-reliance scenario.

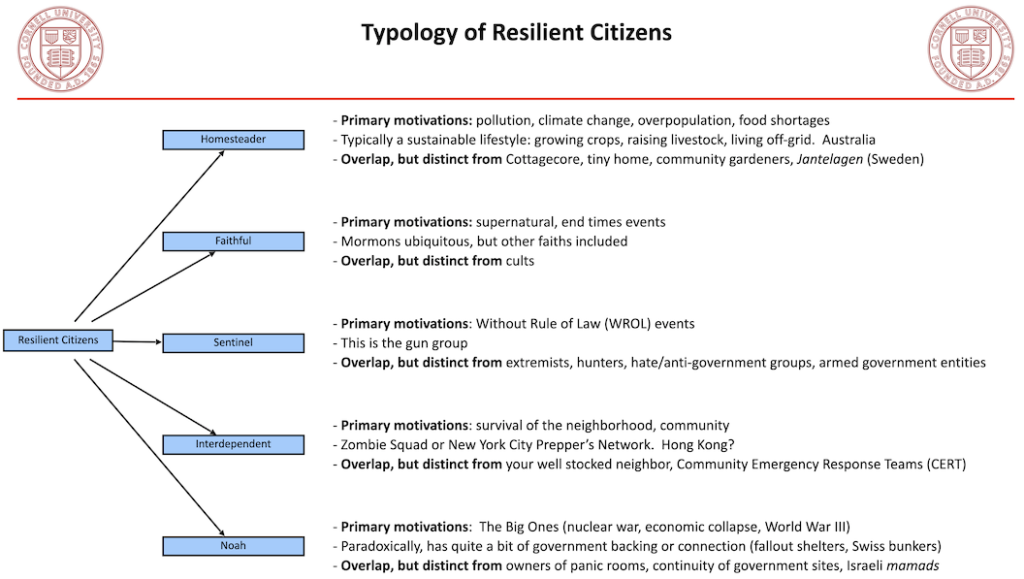

For his paper, Dr. Ellis also split up RCs into five sub-groups: Homesteader, Faithful, Sentinel, Interdependent, and Noah. These variants are witnessed internationally.

The five groups are defined by methodology and motivation. eg. Sentinels are largely defined by their use of firearms, but their primary motivation is adapting to a world without rule of law, while many Mormon groups are primarily motivated by their faith, although they might also stockpile guns and ammo.

Ellis acknowledges that many people could be a mix of these different types. For example, a faith community of preppers would have overlap in both the Faithful and Interdependent categories.

Overall, preppers are motivated by a diffuse set of variables and exhibit wide variance in response. Thus, their divisional boundaries are not set in stone but instead represent a spectrum, with traits that overlap both within prepper circles and out to wider human activities such as gardening, hunting, and home security. Dr. Ellis hopes that future research can uncover cultural and government factors which may stimulate more people to become RCs.

We largely reject synthetic barriers between preparedness groups, because motivations are less important than being responsible, prepared citizens. But these classifications can be useful for both academic categorization and to help aspiring Resilient Citizens know where they can find other like-minded people.

What group(s) do you fall into? Do you agree with the classifications?

Homesteader

Homesteaders are the classic “back to the land” types, who emphasize escaping the rat race of the city to produce their own food by gardening, keeping livestock, and beekeeping. They commonly share an affinity with those who adopt low-energy housing like earth homes and tiny houses, as well as live off-grid.

Ellis says that homesteaders’ primary motivations include food shortages, pollution, and climate change. Research shows that homesteaders generally share a sense of government failure. Due to that environmental focus, the homesteader path is often preferred by those left-of-center:

Community and especially urban gardens are often multiracial spaces, especially in the larger cities, and share food security concerns, which overlap with those of preppers. Others focus on – or tie-in – reduction in their carbon footprint or need for municipal services. The Canadian documentary Life Off Grid featured Lasqueti Island residents in British Columbia. These individuals are disconnected from electric transmission lines or city plumbing and rely on assorted self-supplied power and water. Not all those who live off-grid or practice urban homesteading are resilient citizens, though.

Where to find them: Homesteaders are homebodies by nature. Usually, the best way to make contact is to become a customer, buying goods like vegetables, meat, or milk. We’ve made good friends this way, as well as developed a more localized supply chain. Consider joining a local CSA or visiting farmers’ markets and craft fairs.

Related guides:

- Beginner’s guide to survival gardening

- How to find, buy, and store garden seeds

- Why and how to compost

- Best foods to grow in a survival garden

- Pandemic panic in the city? A country boy on what to expect from rural life

Faithful

The Faithful are driven primarily by religious motivations. Most major religions have some belief in an apocalyptic end-of-time, especially the Abrahamic religions, which all teach some variant of a final day of judgment for the living and dead.

Ellis zeroes in on the Mormon faith, which places a special emphasis on preparedness. “Preparedness is almost as central to Mormons as the faith itself. Each ward (a local level unit) is required to have a natural disaster emergency plan, and ward leaders are equipped, by the church, with radios and satellite phones,” Ellis says.

Ellis continues:

Membership association with the Mormon church was statistically significant for higher levels of disaster preparedness in first responders such as police officers and firefighters (De Jarnatt, 2019). The Mormons have several reasons to prepare; not only are they awaiting the end of the world or even commonly occurring natural disasters, but they also have a history of government persecution.

The LDS church encourages its members to have a supply of food and water stockpiled at all times. It also runs a network of storehouses, where both members and non-members can buy food in bulk. An unendorsed LDS group publishes an emergency preparedness guide as well.

Where to find them: Church, obviously, though we don’t recommend joining a church just to make preparedness contacts. However, if you already attend a church, consider forming a mutual assistance group with other members.

Related guides:

- The LDS food plan can help you build a pantry in less than 12 months

- Food list: How to build your survival pantry with long-lasting food from the supermarket

- First In First Out: How the “use what you store, store what you use” model makes prepping easy

- Surprise! The dry beans you stockpiled are a pain to cook. Use these tips, tricks, & best practices

- Recipe review: pinto bean fudge

Sentinel

Sentinels are all about guns. While many have commonalities with homesteaders, the primary concern of Sentinels is a lawless scenario where everyone is on their own for security. Sentinels are what many people think of when they imagine preppers. Sentinels prefer to live in areas with like-minded gun owners for collective security.

And according to Ellis, Sentinels are a growing demographic:

Calls to defund or abolish police forces across the nation and the multi-week existence of CHAZ/CHOP (Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone/Capitol Hill Occupation Protest) in Seattle only fuel fears or rational calculations that cities at best, or America at worst, is headed for far higher levels of internal violence and strife. And, while the jump in firearm purchases does not immediately indicate a rise in resilient citizens, the combination of urban flight to less dense areas could be a prelude to a dramatic shift in their numbers and demographics. The trend is bipartisan.

Where to find them: Visit or join respectable gun clubs. Take classes on concealed carry, self-defense, and tactical shooting. You might also make contacts at gun shows, but they’re infamous in the gun community for their carnival-like atmosphere.

Related guides:

- Beginner’s guide to guns

- The best choices for your first firearm

- Where and how to buy ammunition

- The best bulletproof body armor when SHTF

- Best plate carrier

- How to prepare for and survive civil unrest

- Easy ways to harden your home against intruders

Interdependent

Perhaps the trickiest group to pin down, the Interdependent focus primarily on community.

While many of Ellis’ archetypes are secretive, the Interdependent are the most open to the public in the hopes of building broader communities:

What drives these individuals is not a singular disaster, but rather any event that threatens the local area in which they live or a catastrophe that causes an assembling of fellow Interdependent individuals or resilient citizens writ large. Their composition could potentially be vast but their commonality is community. Their presence belies the argument that all preppers are insular and care only about their own protection.

As examples, Ellis mentions the Cajun Navy, the New York City Prepper’s Network, and Zombie Squad. There are a number of mutual assistance groups (MAGs) scattered nationwide that seek to train members and share resources.

Where to find them: Seek out MAGs in your community or create your own. Get to know your neighbors well enough to discuss preparedness with them.

Related guides:

- Why you should share your prepping and recruit others

- A gracious “welcome to the community!” is better than “I told you so!”

- CERT training: Community Emergency Response Team

- Beginner’s guide to amateur (ham) radio for preppers

Noah

The final prepper archetype is also the most stereotypical: the “Noah” prepper, who’s preparing to shelter in a bunker to survive a world-ending calamity. Noahs are the opposite of Interdependents, preferring to go it alone when disaster strikes.

This group tends to be both secretive and wealthy, with many in Silicon Valley and on Wall Street among the ranks. Many in those groups already have panic rooms installed in their homes. A personal bunker is just an extension of the same concept.

Noahs don’t necessarily own literal bunkers. Instead, they may strategically relocate to a remote country like New Zealand (such as Valve CEO Gabe Newell, who was stranded in New Zealand during the initial COVID-19 pandemic and recently decided to become a permanent resident.)

For those who can’t afford a bunker or to relocate to the other side of the world, many have chosen an area called the American Redoubt, which spans from Eastern Washington through Wyoming and has proven to be one of the areas in the United States more resilient to disasters, both natural and otherwise.

Where to find them: They’ll let you know if they want to be found.

Related articles:

You are reporting the comment """ by on