If you find yourself in a situation where you need to drink wild water to survive, you want to treat that water so that contamination doesn’t make you sick. Bacteria and protozoa, such as giardia and cryptosporidium, are the common threats that can make you violently ill at the worst time.

Yet the common advice among survival instructors and in the marketing language for water treatment products is that you don’t really need to worry about viruses in water in places like the US and Canada. For example:

- “Water-borne viruses aren’t a threat in the US, Canada, parts of Europe, and Australia, so a filter is just fine,” Adrienne Donica in Popular Mechanics.

- “Fortunately, harmful viruses are extremely rare in surface waters,” Cliff Jacobson in Scouting Magazine.

- “Viruses are not commonly transmitted in water,” Sawyer’s pamphlet What Hikers & Campers Need to Know.

We repeat this expert advice, too, in places like the water essentials video course and in reviews of portable water filters for go-bags.

More: Best water purification tablets (and other portable purifiers)

But… why? Why aren’t viruses a thing you need to be worried about in developed countries, especially since viruses are biological threats that make people sick just like bacteria?

Summary:

- The vast majority of waterborne viruses that can hurt you came from the feces of another person. If you remember to avoid areas where water and human poop mix, then you should be okay just treating the standard bacteria/protozoa threats.

- Developed areas, like the United States and Canada, have proper sanitation systems that (usually) do a good job of keeping poo separate from water people use. Other parts of the world can’t make that claim, and thus they have more waterborne virus problems.

- If there aren’t many people around, that means it’s unlikely a virus was introduced into the water and it’s unlikely the virus would stick around since there aren’t enough humans to infect and keep it going.

- So when experts/marketing make the common “don’t worry about it” claim, their thinking is that if you’re near civilization, then a proper sanitation system is in place, and if you’re in the wilderness, then there isn’t enough human density to cause a problem.

- That could change in a natural disaster that overloads water grids — eg. urban flood waters after a hurricane often have huge amounts of fecal material — or in other situations where people are suddenly crammed together with poor hygiene, such as an evacuee camp.

- Contrary to what might seem intuitive, high temperatures have been shown to decrease viral activity, with viruses surviving better in cold temperatures.

Waterborne viruses to beware of

There is a slew of viruses that thrive in freshwater. The World Health Organization has identified six categories in particular:

- Adenovirus

- Astrovirus

- Hepatitis A and E

- Rotavirus

- Norovirus and other caliciviruses

- Enteroviruses like coxsackieviruses and polioviruses

Most of these viruses will give you diarrhea, and rotavirus, in particular, is the leading global cause of severe diarrhea in children under 5. The CDC identifies noroviruses as the leading cause of foodborne illness (ie. food poisoning). And hepatitis is particularly nasty, as is polio, which can cause paralysis, especially in children. While polio has largely been eradicated in the developed world, it’s an ongoing challenge in developing countries.

Why first-world areas usually don’t have viruses in water

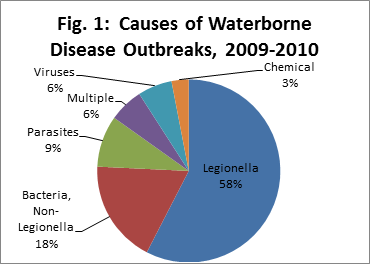

A study on waterborne disease outbreaks in the United States from 2009 to 2010 found that the vast majority of them were caused by bacteria, specifically Legionella (which causes Legionnaires’ disease). Bacteria caused 76% of waterborne illnesses in that time period, while viruses only accounted for 6%.

There’s a difference between the presence of a virus and whether or not it causes an outbreak. For example, the Minnesota Department of Health found in 2014 that 30% of Minnesota’s drinking water wells had viral contaminants, but that didn’t result in a massive problem.

Viral outbreaks in American waters are rare enough that when they occur, they’re news events, like rafters becoming infected with norovirus from the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon, which happens every few years.

So if viruses are known to exist in North American waters, why do many experts say that viruses aren’t a common concern when drinking unknown water?

To quote Satre: “Hell is other people.”

Viruses are typically adapted to infect a specific species, like humans. So if a waterway doesn’t have a great deal of human contact, it’s less likely to contain human-specific viruses. The most common vector for waterborne viruses is fecal matter, which is why it’s so important to do your business far away from water sources.

I spoke with Patrick Hurst of the popular Sawyer Products brand for some additional insight. “It’s all about the type of water. You have hepatitis and do your business upstream from me, I’d have to be consuming raw, unfiltered sewage water to contract that virus. The viruses are very fragile,” he said.

“Viruses like that need a host, they’re very fragile, they hop from host to host,” Hurst said.

Even in developing nations with poor sanitation, viruses may not be as much of a concern as you might think. “If I were going to central Africa, should I worry about viruses? Maybe, maybe not,” Hurst said.

Sawyer only warns of viruses in three areas: refugee camps in Afghanistan and Iraq, and some African nations.

Waterborne viruses are a problem in less-developed nations for two simple reasons: poorer sanitation and higher population density located around and depending on those unclean water sources. So you should suspect viral contamination in heavily trafficked waterways like those near popular campsites.

Likewise, waterborne viruses are rarer in developed nations primarily because of better sanitation practices — we don’t pump raw sewage into water sources. And remote areas, like where you would go camping or hiking, likey don’t have a lot of human contact.

When you should worry

However, some water bodies in North America are notoriously problematic for viruses, such as the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon. A 2009 study published in Wilderness and Environmental Medicine offered some explanations about why the Grand Canyon is such a hotspot for viruses: “The authors concluded that poor sanitation on the trail, scarce water supplies, and crowding may have contributed to increased risk of norovirus among long-distance hikers.”

In other words, the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon has many of the same problems water bodies in the developing world do. In the years studied (2003-2004), 22,000 people rafted on those waters every year. Rafters are close together and often get sloppy with sanitation, which leads to illness. The study said that disease outbreaks can make things exponentially worse because sick rafters start vomiting or pooping in the water.

Even as virally problematic as the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon is, outbreaks seem to only happen every few years.

While viruses in water aren’t a concern in developed nations now, things could change if we suffer a great societal collapse. Even small-scale collapses, like floods in which water and sewage mix, can wreak havoc on the water supply.

While you can’t visually tell if a body of water has viruses, Hurst gave me some clues to look for:

- Poor sanitation, eg. raw sewage being piped into a body of water

- Stagnant water, such as ponds and lakes

- Viral outbreaks in the area

- People drinking stagnant water, especially out of puddles

Again, these are red flags, but there’s no guarantee a body of water won’t have viruses even if you don’t see these warning signs.

I also contacted the CDC for comment but did not receive a response.

Viruses seem to do better in colder waters

Viruses are also very temperature sensitive, but a common survival myth is that viruses thrive in heat and do poorly in the cold. However, a review of the science shows the opposite.

An Intervirology report titled “Survival of Viruses in Water” explains: “It has been universally demonstrated that higher temperatures mean faster viral inactivation. At low temperatures above freezing, viruses may survive for extended periods of time, often longer than the duration of the study, and sometimes for several years.”

The study offers many examples of viruses degrading at higher temperatures:

- “…poliovirus, echovirus, and coxsackievirus populations in seawater were reduced by 5 log units in less than a week at 37°C [98.6°F], while it took 1 year at 4°C [39.2°F] in laboratory conditions.”

- “In mineral water, poliovirus lost 1 log unit in 330 days at 4°C [39.2°F], while it took 60 days at 23°C [73.4°F].”

- “Astrovirus in tap water was reduced by 2 log units in 60 days at 4°C [39.2°F] and 30 days at 20°C [68°F].”

- “Adenovirus in groundwater lost 1 log unit in 132 days at 4°C [39.2°F], and in 36 days at 20°C [68°F].”

Another study analyzed norovirus cases in England and Wales from 1993 to 2006 and determined, “Increases in norovirus are associated with cold, dry temperature, low population immunity and the emergence of novel genogroup 2 type 4 antigenic variants.” The study also found that, “For a 1°C increase in temperature in the previous 49-day period, there was a 15% decrease in norovirus reports…” Finally, “Temperature variation was associated with the largest attributable fraction: 60% of cases.”

Norovirus is particularly resilient, able to withstand low temperatures, high temperatures, and even most disinfectants.

However, the aforementioned study of the Grand Canyon pointed that high temperatures can exacerbate the symptoms of viral infections:

Several factors exacerbate disease severity on the river. The rafters are frequently exposed to high heat during the rafting season, when temperatures in the canyon often exceed 100F. High temperatures hasten dehydration as a result of vomiting and diarrhea and increase disease severity.

You are reporting the comment """ by on