This fall, Cornell University in Ithaca, NY, will reopen. Yes, students will be wearing masks, and yes, there will be social distancing and lots of rules about physical contact, but students will be on campus. How could that be, when Harvard is moving most of its classes online and only bringing 40% of students back to campus? And most universities in the California State System are holding classes online!

To find out what makes going back to school possible for Cornell and not these other places, I got on the phone with Dr. Peter Frazier, one of the data scientists responsible for the COVID-19 modeling behind Cornell’s reopening plan.

The bottom line: Cornell will attempt to create a campus-sized “green zone” in the midst of the US epidemic by using the same test-trace-isolate protocol that has been successfully used in places like Singapore and Beijing. This is an experiment we should all keep an eye on, because if it works, then this could be applied more broadly to other places in the US. In short, Cornell’s model may (or may not) give you a glimpse of your future if an area where you live adopts this approach.

How the Cornell model works

Like colleges, universities, and K-12 schools all around the country, Cornell shut down its campus this spring when the coronavirus pandemic took hold in the United States. And like all those other institutions, Cornell has spent the rest of spring and summer trying to figure out what it would take to bring students back safely. For that, they established a Reactivation Committee.

When leaders polled students, faculty, and staff, they learned that many students had plans to return to Ithaca to live together whether campus reopened or not. This is true for many colleges and universities where undergraduate and graduate students find rental homes and apartments to share in the surrounding city.

So the Reactivation Committee looked at it like this: either we reopen campus, bring everyone back, and do rigorous testing and tracing to control the spread of the virus, or we shut campus down and students might contract and spread the virus anyway.

Frazier and his team of research scientists ran models on the main possibilities. Those models suggested that the safest option was to reopen campus under some very precise conditions. Here’s how that plan will work:

- Before students come back to campus, they’ll have to take diagnostic COVID-19 tests.

- When students get to campus, they’ll take another COVID-19 test. “The goal is to have people do a test before they leave home—say you live in St. Louis, get tested in St. Louis. Come to Ithaca, NY, and we’d test you again, so there’d be that sort of testing procedure,” Frazier said.

- Cornell will require Daily Checks through its system before coming on-site for the day. People with even mild symptoms must stay home. (The state of New York requires that all students, researchers, and employees do a daily health assessment, so this isn’t just Cornell.)

- Every member of the Cornell community will get tested again about once a week. So if an outbreak happens, they’ll know right away and be able to control it.

- If someone tests positive for COVID-19, they’ll be required to isolate.

The plan is based on faculty and staff discussions and a modeling report that Frazier and other researchers released on June 15.

No “no-risk” plan

Having so many students together might sound like a big risk. Frazier says he has received panicked emails to the tune of, “What if students throw parties!?” He agrees, it’s not a zero-risk plan.

In fact, the model accounts for some infections. Frazier’s report says that in the median potential future with on-campus instruction, “3.6% of the campus population (1,254 people) become infected, and 0.047% of the campus population (16 people) require hospitalization.”

That’s actually not a high number. For contrast, when the researchers ran the model in a no-open scenario (all online classes), those 1,254 cases rose to around 7,200. Reopening could actually mean less infection.

The report explains:

This is because the loss of asymptomatic screening allows cases to grow significantly in the unmonitored student population. It is also because infections from outside Cornell, a large driver of cases in the residential-campus scenario, continue to drive cases.

In other words, being able to test and monitor faculty, staff, and students on campus means fewer of them will probably be infected than they would be at home, where no one would be able to monitor their health.

That modeling has reassured many in the Cornell community that they’re taking the right step. “Overall, the response has been very positive,” said Frazier. “An interesting thing I’ve noticed is that people have radically different perceptions of the risks involved. A big part of an individual’s response to the plan seems to be, before they heard about it, what was their perception of the risk?”

Now, the researchers are trying to make sure they keep the larger Ithaca community safe, too. “In terms of the impact of Cornell students coming and the impact on the local community, we are doing a detailed analysis of that now,” Frazier said. “We did a not-very-detailed analysis of that before. What seems to be true is that if we do our jobs—and we are going to do our jobs—the number of cases that are brought from students into the broader community will be very small.”

The Cornell green zone

Cornell’s model might sound familiar to those who’ve looked at the COVID-19 response in New Zealand and many parts of Asia. Some countries have been able to slow or stop the spread of COVID-19 by doing a rigorous lockdown with frequent testing. Then, they’ve continued testing while tracing and isolating cases to keep numbers down. They’ve created “green zones” where people can slowly relax distancing measures.

Basically, Cornell is trying to set up its own green zone for the school year, using a pretty similar approach.

My worldview:

1) Short sharp lockdown to get to zero new cases, using as much of Asia, NZ playbook as possible

2) Then test, trace, isolate to maintain a green zone

3) This minimizes both economic & viral damage

4) Alternative is halfway lockdown that stops economy but not virus https://t.co/49hkzU2wc1— Balaji S. Srinivasan (@balajis) April 26, 2020

If it works, Cornell’s model will mean that green zones are possible within the United States. That would be a big deal.

Could this model work anywhere?

Frazier explained that there are some parts of Cornell’s model that would be pretty hard to duplicate. ”The really important part of the plan we have at Cornell isn’t going to translate to other environments,” he said. “A big cornerstone of the plan at Cornell is asymptomatic screening. So that’s taking everyone on campus and also students who live off campus, and testing them on a regular basis, once a week roughly.”

“If we find someone who is positive, then we’ll isolate them and do contact tracing. What that does is it finds individuals who are infectious, but who are not yet symptomatic or will never become symptomatic. You need to have the ability to do that.”

Most American cities do not have the capacity to test everyone in the area once a week. Most schools don’t have that either.

“Our test capacity comes from two places,” Frazier said. “One is a local hospital. And many places have a local hospital. The other place we have access to is the Animal Health Diagnostic Center. It’s run by the veterinary college and it’s a big facility designed to do PCR testing for the viruses in animals. That PCR capacity is basically there for helping to control animal epidemics. So that capacity is there and those people are great and have a great operation. They have expertise in doing pool testing. So that’s kind of a thing that’s special to us.”

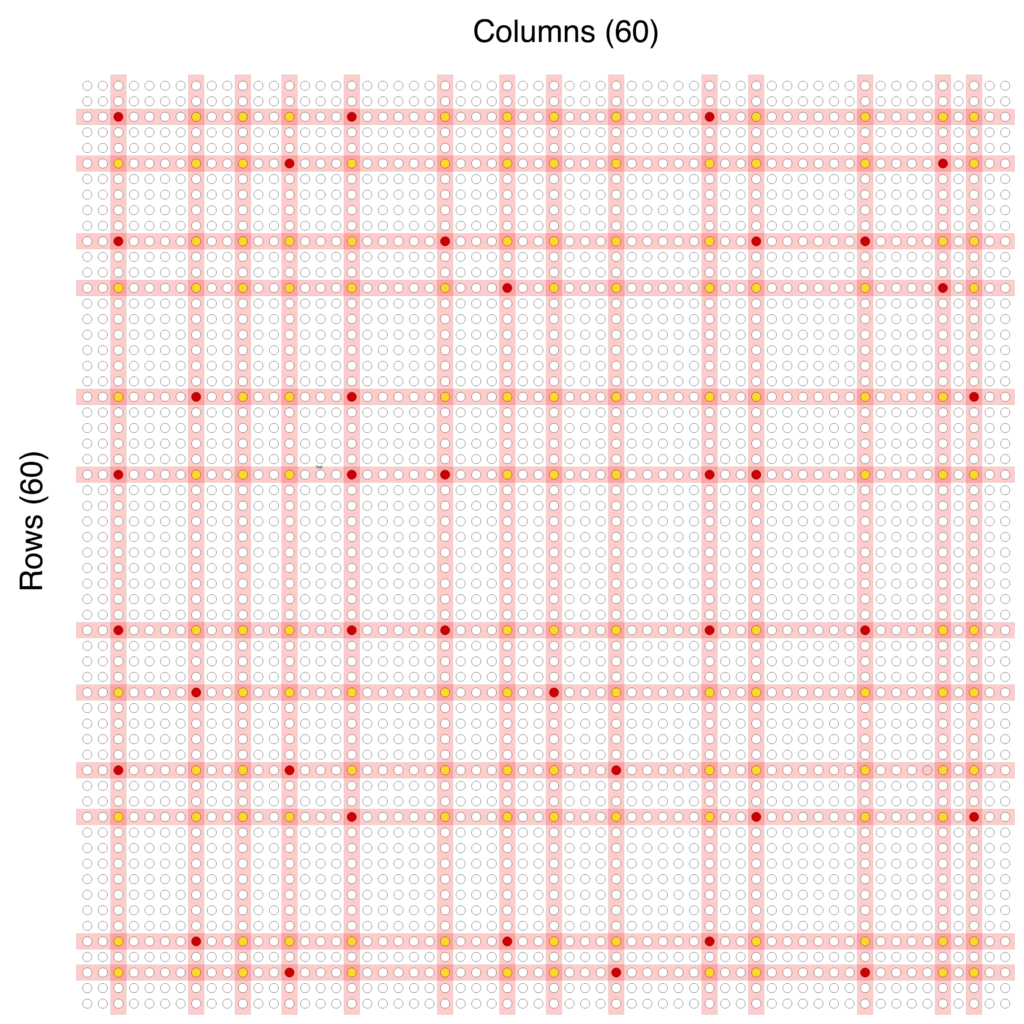

Pool testing is a big part of Frazier’s model. To test this way, researchers make a grid of test swabs and test groups all together. If a group tests positive for COVID-19, Cornell will retest everyone in that pool individually to diagnose and isolate the infected person.

The pool testing model is much more efficient than testing every single swab separately, as we’re doing now. Frazier and colleagues believe if scaled up, pool testing could work to test the entire United States population. As Frazier and colleagues wrote in a recent white paper: “This protocol is extraordinarily efficient. For example, if our array is 70×70, then we can test 4,900 samples with only 2×70=140 PCR tests. While we would not save on swabs, PCR testing capacity is the limiting factor over the long term in scaling up testing.”

“Pool testing was invented in the 1940s, so it’s not like we’re doing something totally crazy,” said Frazier. “It is a pretty widespread, kind of well-understood methodology. I do think that any sort of reasonably sophisticated lab probably has the wherewithal, especially seeing papers published in the literature, they do probably have the capability to do this and set this up on their own.”

What this could mean for future “green zones”

Even without widespread pool testing, everywhere you look, people in the United States are creating green zones in their communities. Some people call them “pandemic pods” or “bubbles.” It’s happening with families and playgroups, with sports teams.

Last month, I drove to visit my parents in our own little “pandemic pod.” I fully locked down from the outside world for multiple weeks and got a negative test result before hopping in the car and driving across four states to see them. It wasn’t risk-free, but it meant I could see my family relatively safely and with peace of mind.

This is, effectively, what Cornell is trying to do for its faculty, staff, and students. As the rest of the country reopens with catastrophic results, Cornell is trying to make a campus-wide “bubble” using the tools from countries that have done it well. The advantage is that students will be able to see each other, form community in person, and learn from their professors without needing Zoom. As international students at universities without a plan are currently scrambling to figure out whether to leave the United States or not, Cornell’s international students don’t have to worry quite as much.

Families, play groups, and K-12 schools might not have access to Cornell’s pool testing and contact tracing resources. I don’t, for instance, know of any K-12 schools with associated animal hospitals that regularly do pool testing. But “other parts of our plan do translate,” Frazier said.

Depending on their resources, other schools and institutions may be able to implement parts of Cornell’s program, like:

- A wide variety of social distancing measures

- De-densifying lecture halls

- Mandating the use of masks

- Daily health checks before arrival

- Restrictions on the size of social gatherings (no more than 10 people)

- A wide variety of measures for increasing cleaning

- Changes to the heating and air conditioning systems

Without access to regular testing, though, Cornell’s plan would be much riskier. They may have ended up with a plan that looks more like California or Harvard’s.

What’s for sure: we’ll be watching Cornell’s first semester very closely. If it works, this experiment could change how the rest of the country treats the pandemic.

You are reporting the comment """ by on