Scientists published a preprint manuscript Thursday with genetic evidence that a new mutation of SARS-CoV-2, known as Spike D614G, is more transmissible than the original strain first identified in Wuhan in December.

Although a comparison of hospital records from English COVID-19 patients with the two strains did not yield any evidence that the new strain causes more hospitalizations or deaths among the infected, higher transmissibility makes SARS-CoV-2 harder to contain. This is terrible news.

The team also identified another mutation which, although it doesn’t appear to have the evolutionary advantages of Spike D614G, appears in a collection of lineages indicating that it probably spread by recombination, the first confirmation that this potent mutation mechanism is occurring in SARS-CoV-2 in humans.

How this study was performed

The sequencing of the SARS-CoV-2 genome in the first week of January definitively established that the outbreak in Wuhan was caused by a novel coronavirus. Since then, scientists have been sequencing samples from COVID-19 patients around the world and depositing them in a databank called GISAID, which was set up for influenza sequences and has expanded to coronaviruses. The team behind this research, based in Sheffield, Los Alamos, and Durham, has a software pipeline that ingests this database every day, checking the latest sequences and comparing them to prior ones.

This kind of comparison tracks where different strains of the virus are moving over time, which resulted in the news that most introgressions of SARS-CoV-2 to New York came from Europe. It also allows the identification of new mutations and assessment of their frequency over time, and assessment of whether they may matter clinically or in therapeutic development.

This kind of research has led to a lot of headlines in the mainstream press like “scientists identify [some number] strains of COVID-19 virus,” and a lot of speculation about whether the SARS-CoV-2 virus has an especially high mutation rate and whether more lethal or more transmissible strains are already out there.

However, experts have consistently said that the mutation rate of SARS-CoV-2 is relatively low and typical of coronaviruses, and that identified strains don’t have clinical significance. Until now.

What the D614G mutation is and why scientists think it makes SARS-CoV-2 more contagious

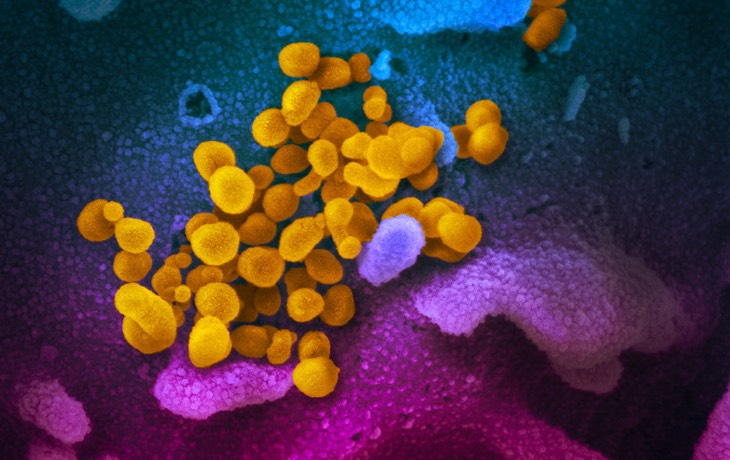

The D614G mutation is an alteration of a single amino acid on the Spike protein of SARS-CoV-2, at position 614, from aspartic acid (D) to glycine (G). The spike protein, which forms the “crown” appearance on an electron micrograph and gives coronaviruses their name, protrudes from the viral envelope and recognizes the ACE2 receptor on mammalian cells, allowing the virus to enter. While aspartic acid is a negatively charged polar residue with some bulk to it, glycine is neutral and is the smallest and simplest amino acid.

The D614G mutation appeared first in a single sample from Wuhan and then several more in Europe in February, and has become much more common since then, growing in prevalence over time. In theory, this could be because of “founder effects,” wherein the D614G doesn’t make a difference but was “carried along” with the rapid spread of a “founder” strain that wound up infecting many people. Because almost all strains carry some mutations, and some strains enjoy outsized reproductive success, founder effects driving some mutations to high prevalence are widely seen.

The team from Sheffield tested this hypothesis by looking at the pattern of increasing D614G prevalence over space and time. What they found was a repeated pattern of D614G strains of SARS-CoV-2 rising in prevalence over time in countries with both increasing and decreasing infection rates. This suggests that D614G is not just the beneficiary of a founder effect, but is actually making SARS-CoV-2 more transmissible. If so, it is the first known epidemiologically significant mutation in the COVID-19 pandemic.

Since its emergence, the D614G strain has become the dominant one around the world, and by the end of March made up about 75% of samples being submitted to GISAID in the USA, and the majority in other places.

How D614G might work

This leaves unanswered the question of how D614G makes SARS-CoV-2 more transmissible. Residue 614 on the spike protein is not a key recognition residue for ACE2, nor is it a key recognition residue for antibodies against the spike protein, which are two leading areas where scientists usually look for clinically significant mutations in coronaviruses.

However, the authors posit two possibilities. One, suggested by 3D modeling, is that the 614 residue has a hydrogen bond interaction with another nearby residue which alters the shape of the ACE2 recognition region, altering its activity. The second, suggested by limited immunological evidence, is that a nearby antibody recognition domain is larger than previously believed and the 614 residue is part of it. This could make it harder for the body to develop neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, or easier for SARS-CoV-2 to function despite antibody binding in some circumstances.

Why D614G probably doesn’t make SARS-CoV-2 deadlier or harder to treat

All of this leaves unanswered an important question: does the Spike D614G mutation matter clinically? A person carrying this strain instead of another may be more contagious, but will they have different symptoms or a greater risk of death? Luckily, the answer appears to be no.

To answer this question, the Sheffield team consulted a database of 453 SARS-CoV-2 genomes matched with medical records from the donor patients, available at their university’s teaching hospital. Using a variety of statistical and machine-learning methods, they looked for evidence that COVID-19 patients who were carriers of the D614G mutation had a higher risk of hospitalization or death, and came up empty-handed.

In addition, Spike protein residue 614 does not currently appear to be a target of any known therapies.

Thus, while the D614G mutation is probably more transmissible, there’s currently no evidence that it’s more lethal or will frustrate current therapy efforts.

S943P: Evidence of SARS-CoV-2 recombination

In addition, the work presents evidence that another spike protein mutant, S943P, has been involved in recombination events. They conclude this because S943P is seen in multiple genetic backgrounds among samples in Belgium, but never seen outside Belgium (so far). The chance that it would independently arise multiple times in the same population, but never anywhere else, is considered remote, leading to the conclusion that this mutation has recombined in Belgium since it first emerged.

The S943P mutation doesn’t appear to have significance of its own, and it’s not common, but it’s important because it shows that recombination has been occurring in SARS-CoV-2 in humans. Recombination occurs when one cell is infected with multiple strains of a virus, and copies of their genomes undergo homologous recombination, creating a sequence with parts of both genomes which goes on to be incorporated into virions and form a new strain. It’s important because, like sexual reproduction, it allows mutations from multiple sources to be combined together. It’s known to be important in coronavirus evolution, but until now scientists had not confirmed it was happening in humans during the pandemic.

In theory, future recombination events could allow mutations with greater significance to combine together and form new, yet-worse strains of SARS-CoV-2.

What this and similar work will mean for the future of the pandemic

This is significant and very bad news, for a number of reasons:

- A more transmissible strain of SARS-CoV-2 means the epidemic might be harder to contain. A strain with a higher R0 value will spread more rapidly when it’s not controlled, and take more stringent measures to contain. It will even resist vaccination more, taking a more effective vaccine or higher inoculation penetration to protect populations, not because a vaccine will be less effective but just because R must be reduced more from a higher starting point to get below 1. It’s going to be very important to get some estimates of how much more transmissible the D614G mutation makes SARS-CoV-2, so we can proceed accordingly.

- This is the first epidemiologically important mutation discovered in SARS-CoV-2 so far, raising the prospect that we’ll see more such mutations in the future. We are only four months into the pandemic, and only a tiny percentage of humans have been infected so far, and we’ve already seen a harmful mutation emerge.

- The confirmation that recombination is operating in humans means the potential impact of future damaging mutations is worse.

This news also reinforces a couple of points we’ve been making repeatedly for a long time, like the value of rapid and widespread genetics research and other recently-developed biotechnology methods in this pandemic, and the critical importance of keeping caseloads down everywhere in the world. Every additional case is another opportunity for damaging mutations to emerge.

If this pre-print passes peer review and the results hold up, it is very unfortunate news. Expect to hear more about this in the mainstream press soon.

You are reporting the comment """ by on