There’s a new app in town, and it might be able to help you accurately evaluate your risk of contracting COVID-19 without violating your privacy. It’s called Hunala, and it was designed by Dr. Nicholas A. Christakis, a physician and professor of Social and Natural Science at Yale.

The idea behind Hunala is to leverage Dr. Christakis’ experience with sociology and network science to forecast a person’s risk of contracting COVID-19 based on their behavior, location, symptoms, and social network. Unlike contact tracing apps that simply track a person’s location and confirmed cases around them, Hunala should be able to look at social behaviors and forecast future risk. So, as the app says when you first download it, it can help stop outbreaks before they happen.

I downloaded Hunala this week to evaluate it for use as a prep, and I think if everyone downloaded Hunala and used it as instructed (without lying about behavior), it could work really well to stop the next outbreak. But it might not be that effective at this point in the COVID-19 pandemic.

Here’s what you need to know about using Hunala:

- Hunala is pretty simple to use. Getting started takes just a few minutes.

- In testing, the app didn’t reliably remind me to fill out my daily check-in.

- Unlike other contact tracing apps, Hunala doesn’t track your location or who you see. Instead, it relies on your social network and daily check-ins to calculate future risk. As far as tracking apps are concerned, Hunala is probably the most private one out there.

- The app works best if you know it’ll be reliably used by people in your main social circle.

- Since the app is anonymized for privacy, it’s impossible to know why your risk has gone up or down. It’s therefore also really hard to know which behaviors you should change to reduce risk of contracting COVID-19.

- Hunala seems best suited as a prep for areas where case counts are rising but not already through the roof. It’s also most useful in social networks where everyone is comfortable using the app.

How it works

When Hunala first launched this summer, Christakis said in a tweet the app would be like “Waze for COVID-19.” He was referring to the navigation app that crowdsources traffic information to help drivers find the most efficient route to their destination. Like Waze, Hunala crowdsources information about social distancing, symptoms, and case numbers to tell you how concerned you should be about COVID-19.

For a while, we’ve been saying that the future of the pandemic was looking more and more local. In other words, at this stage in the pandemic, outbreaks are happening on a local scale in smaller social circles. So ideally, Hunala can help you track your very close social circle and change your behavior based on local risk.

Like Waze, a big feature of Hunala is that it’s anonymous. The app notifies you if your risk goes up, but it doesn’t tell you who in your social circle is experiencing COVID-19 symptoms or who knows someone who just tested positive. You’re just supposed to modify your behavior based on your level of risk.

New features added to our app, HUNALA, that enhance ease and precision.

It’s a FORCASTING app, like Waze for COVID-19.

The user interface is better and the backend is better.

This is a powerful tool for people returning to work and for their firms. https://t.co/dJGuWQL19J 24/

— Nicholas A. Christakis (@NAChristakis) July 1, 2020

The app’s name, Hunala, comes from an acronym used by scientists who work at the Human Nature Lab at Yale, a lab that studies how human networks could impact health. The lab is perfectly positioned to research social networks and the spread of COVID-19. In fact, Christakis gave a TED talk back in 2010 about “how social networks predict epidemics.”

He has long argued that if we could figure out who’s at the center of a social network and track those people’s behaviors, we could predict how an epidemic would spread. If we could alert those people that they’re at a high risk of contracting or spreading a disease, they might change their behavior.

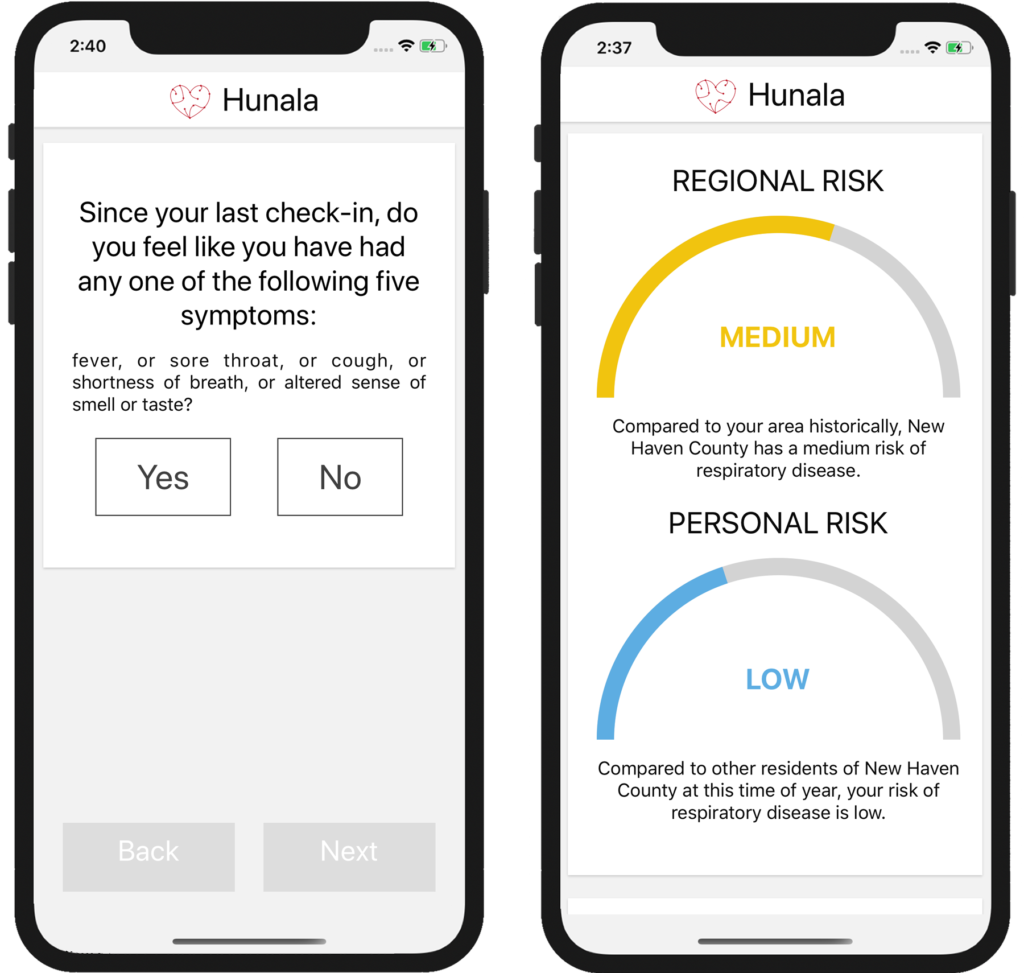

That’s basically how Hunala works. When you download the app, you answer a few questions about your age, health, social interactions, COVID-19 symptoms, and location. Then, crucially, it connects you with people you live with and people you see on a regular basis. Setting it up took me about a minute, and it also takes about a minute to answer check-in questions every day.

The app uses data from USAFacts.org and the CDC to figure out how many people in your county are infected at a time. Based on those numbers, the app calculates risk for people in your area. Then it uses information about your social interactions and those of people in your network to calculate your personal risk.

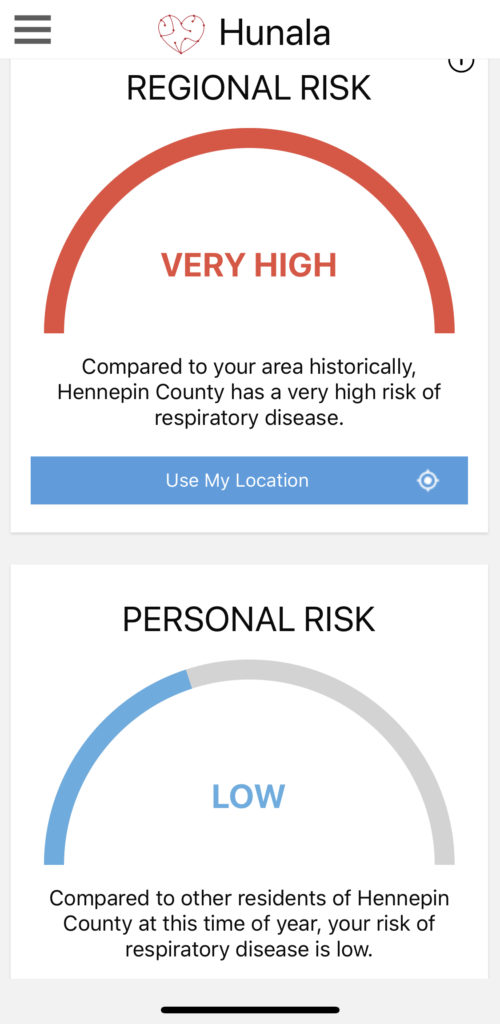

This morning when I checked in, the app showed that while my area has a “VERY HIGH” rate of respiratory disease, my own personal risk was “LOW.”

Hunala calculates individual risk based on an individual’s health, social behaviors, and extended social network. So since I’m not experiencing symptoms and I’ve been practicing social distancing and leaving the house very rarely, the app thinks my risk of contracting COVID-19 is “low.”

I’m skeptical of the low risk since:

- My area’s risk is very high, so my personal risk can’t be that low. I’ve been staying home for the most part, but I also went for a socially-distanced walk with a friend yesterday and reported it to the app. Shouldn’t that have raised my risk?

- Hunala runs on trust. I have to trust that my friends and family are accurately recording their behaviors for my risk-level to be accurate.

- Because Hunala is anonymized, I have no idea if anyone in my social circle actually downloaded the app. And if my network isn’t using the app, the crowdsourcing doesn’t really work. Imagine if no one submitted traffic reports to Waze. The app would be useless.

Basically, the app will only show me I have a high risk if my friends and family start using it and reporting their own symptoms and behavior. Until then, my risk could look misleadingly low.

I worry that the app could give people a false sense of security. If you internalize the message that you’re low risk compared to other people in your area, you might let your guard down. That would be a mistake if you’re in a very high-risk county (that’s the vast majority of the United States right now), especially if friends and family aren’t reliably using the app.

I can imagine the app working well if COVID numbers in my area were still really low. With low regional and personal risk, I’d feel good about going to the store with a mask on or walking the dog. But now that the pandemic is really underway where I live, Hunala isn’t that useful.

Anonymity, privacy, and connecting with friends

Before launching Hunala, Christakis spoke with The Atlantic and said he was concerned about surveillance and the threats of contact tracing and tracking apps on individual privacy. His solution was to develop an app that would be anonymized. So you download Hunala and give the app access to your contacts so you can invite the friends and family you see regularly to download the app.

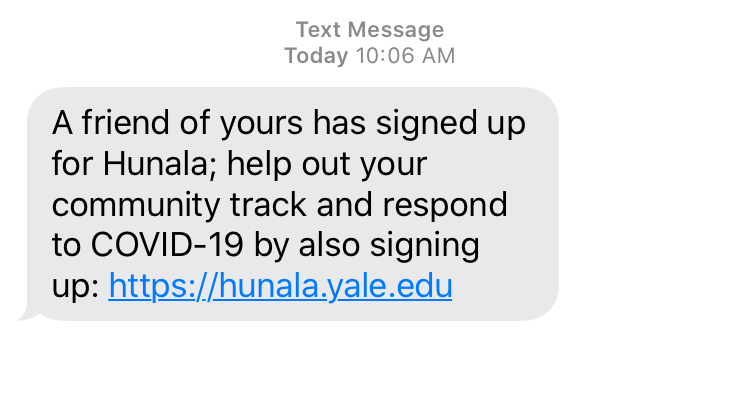

While using the app, it’s unclear how these invitations will be sent, what they’ll say, or even what will happen after they’re sent. I sent invites to the people I live with and the few friends with whom I go on socially-distanced walks around the neighborhood from time to time. Nothing happened, and no one said anything to me about the app.

Curious about whether my network had been contacted at all, I asked my partner if he’d heard of Hunala. “Yeah,” he said. “I think your mom invited me to sign up for that app or something.”

He showed me the text message he’d received from the app. It was anonymized to a fault. He actually thought it was spam and ignored it. Then, even though Yale claims the app will only message contacts once, he got the same text message again today.

So far, I still don’t think anyone in my social circle has downloaded Hunala. I wonder if that’s because my friends and family don’t know I’m the one who invited them. If I wanted to make sure my friends and family used the app, I’d have to reach out to each person individually to help them understand what the app does and why they should download it. And I’d have to reassure them that “community tracking” doesn’t mean the app will track their location. That sounds like a lot of work.

Still, Hunala’s focus on privacy is nice to see, and with a few improvements like personalized invitations, I can see it catching on.

The bottom line

If everyone used Hunala, I could see it becoming a really great prep. “This is a tool, just like masks,” Dr. Christakis told Yale News in June. “We are alive at a moment when a new pathogen has been introduced to our species. It’s not going away, and millions of us will be affected.” He’s right. Hunala is a great tool that could be used effectively at the start of the next epidemic to help people change their behavior.

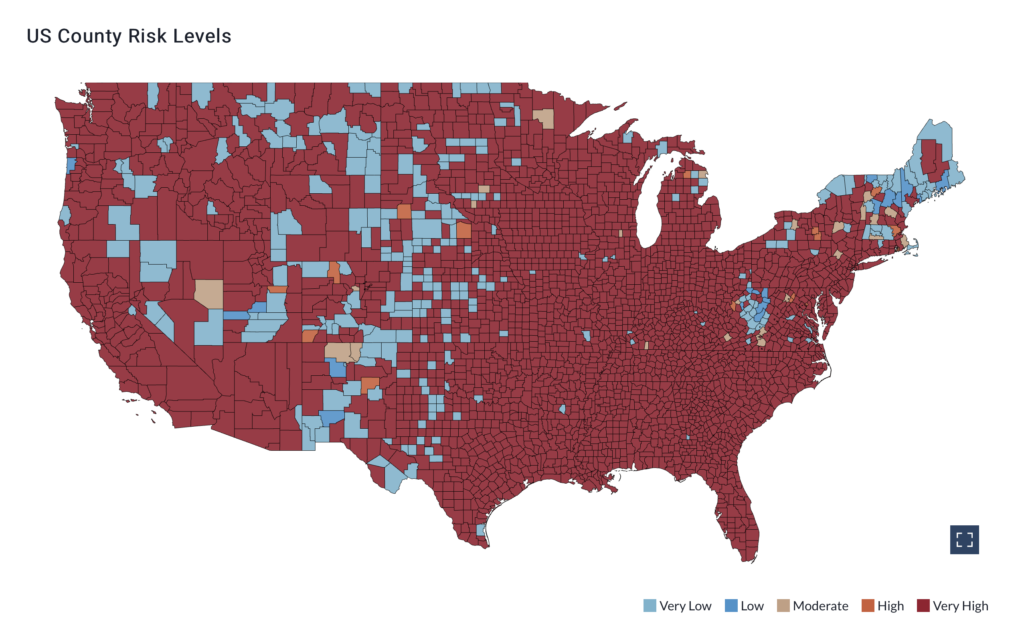

But we are not at the start of an epidemic. We are in the middle of a global pandemic and most of our country is currently the deep red of “very high risk.” One look at the above map of the United States and most people know that even if their personal risk is low, it’s still important to exercise caution.

Hunala is great because it’s private. It doesn’t track your location all day long, and it won’t violate your privacy by sharing symptoms or test results with friends. But that’s also its downfall: the heightened privacy means you really have to trust the app’s calculus and your friends and family to take reporting their behaviors and symptoms seriously.

Maybe one day in the future, the app will be smart enough to raise a person’s risk if their friends and family stop responding to daily checks or fail to provide information. If that happens, I’ll be overjoyed. I’ll recommend Hunala to everyone as a prep for future outbreaks.

Until then, I’ll keep using Hunala to see if it catches on. I’m not sure that it will, but it’d be great if it did.

Have you tried Hunala or other contact tracing apps? I’d love to hear about your experience.