Knives have always been one of humanity’s most important survival tools because they’re simple, light, relatively cheap, yet very effective in a wide range of emergencies.

Bladed tools come in different shapes: multi-tools with a knife, pocket knives, axes, machetes, hatchets, and so on.

This guide focuses on the quintessential “jack of all trades, master of none” prepping field knife — a simple blade about the size of your hand — the kind you’d want if you were in an emergency and had only one type of blade.

The field knife is the primary knife you’ll keep in your main BOB/GHB kits. Everything else is either a backup or for more specialized jobs (like a chopping axe you keep in your home supplies). And since your bug out bag is always packed and ready at home, you’ll have this field knife around even if you shelter in place.

More: Learn how to sharpen a knife and buy the right gear (with tips on using random stuff found after an emergency) and how to pick a great aftermarket knife sheath.

Summary:

- The sweet spot is $100-$150, but there are one or two decent choices around $25, great budget choices below $75, and amazing choices around $200-$300.

- If you only have one knife, make it one of these — ideally one in each of your primary bug out and get home bags.

- Knives are versatile, useful to preppers in a wide range of circumstances — but you’re not Rambo and won’t be chopping down big trees or bad guys.

- There are good reasons why most top knives look the same (or even boring) — thousands of years of experience is better than something that looks cool. Don’t get exotic.

- Fixed-blade knives are appropriate for this role — foldable knives are too weak at the hinge.

- 3.5″ to 5.5” blade lengths are the sweet spot for most people because larger knives tend to get unwieldy.

- Heat treatment is more important than type of steel, so don’t worry too much about intricate steel profiles like 1095 vs. 1095 Cro-Van, or 420 vs. 420HC.

- We prefer stainless “super steel” knives for their corrosion resistance, but they’re more expensive than comparable carbon steels.

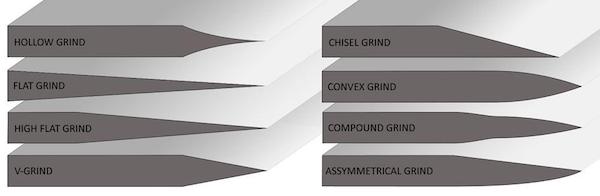

- Knife edges come in different shapes. We prefer convex-shaped edges, but many come in flat “V” shapes, which is fine, and can be easily converted to convex if desired.

- Most sheaths that come with your new knife are bad — manufacturers assume you’ll replace it with something better.

- Practice using and doing basic maintenance on your new knife. It matters!

Full details on how we pick the best prepper knives, competition, scenarios, and more below the fold.

Best bang for your buck:

Fallkniven F1

The best choice for most people is the Fallkniven F1 in VG10 laminate steel. A Japanese-made, Swedish-designed (and used by their Air Force) 3.8″ survival knife that delivers huge bang for your buck — even when as high as $150. The F1 checks all of our criteria for the best survival knives: the right blade length, full-tang strength, fixed blade, drop-point tip, convex edge, excellent balance and feel, and a tough, corrosion-resistant “super steel.” All these qualities converge in a classic, time-tested knife design from a reputable and popular brand.

Most importantly, some of our experts have used and abused the F1 in the field for years, doing everything from camp chores to field dressing wild game — and it never fails to impress, even when compared to more expensive models.

Also great is the new SOG Pillar. SOG has emerged from a bit of a rough patch in recent years. The 5” Pillar, made from the hot new stainless “super steel,” has received rave reviews (including from some of our experts) that marks SOG’s return to form. However, we didn’t pick it over the F1 because it’s generally more expensive and we’d like to see more years of abuse on this new tech.

Carbon alternative:

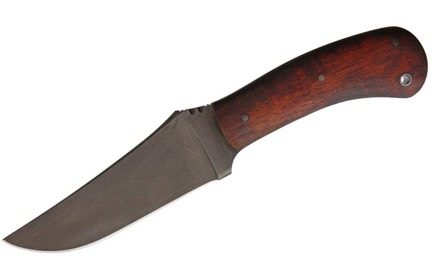

TOPS BOB

Carbon alternative:

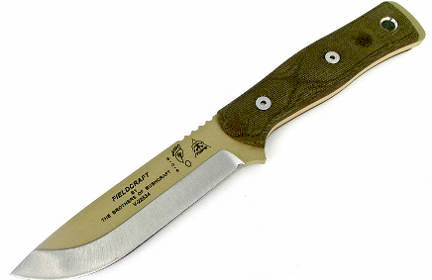

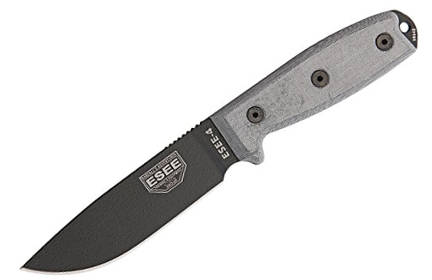

ESEE 4

While our main pick uses a “composite” steel that mixes the best qualities of stainless and carbon steels, some prefer a pure carbon steel. Carbon is tougher and relatively cheaper than stainless, but at the expense of weaker corrosion resistance.

We also recommend the popular TOPS BOB and ESEE 4. Both knives use quality 1095 carbon steel with anti-corrosion coatings that overcome the weaknesses seen on cheaper 1095. Both also use our favorite handle material and share a similar blade design. The TOPS uses a Scandi edge grind that some reviewers find easier to maintain than our usual convex or V grinds, whereas the ESEE uses a classic full-flat V. If you’re new or don’t care, go with the ESEE (which also has an amazing warranty).

We’d be happy to carry any of these also-greats in an emergency (and have!)

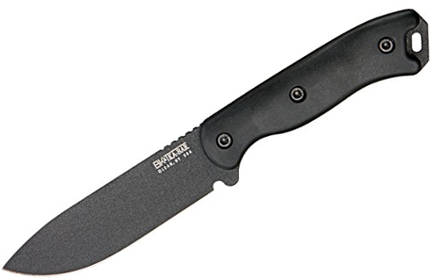

Best knife under $50:

Schrade SCHF56L

Great in the $50-$100 range:

Becker BK16

A good field knife tends to be more expensive than you might assume. However, while you should absolutely avoid most cheap knives — which tend to fail at the worst times — there are a few quality budget survival knives to be found if you know where to look.

The best choices commonly founder under $50 are the Schrade SCHF56L and Morakniv Companion. The sturdy SCHF56L is so near-perfect in design and execution that it could almost be our main pick for this guide. And while the steel isn’t on par with more expensive knives, it’s plenty tough in a pinch and we prefer it over the Companion. The famous Morakniv is the standard entry-level knife recommendation among preppers, with a sterling reputation for the price. It doesn’t have the full-tang design we normally recommend (so it might break under pressure), but the Scandinavian steel is good enough and the compact design offers a ton of utility in a small package.

It’s worth the jump up to the $50-$100 range for the Becker BK16 or the Gerber StrongArm Fine Edge — once you get above $50, the right knife is meaningfully more dependable than the ultra-budget models.

The BK16 is popular because it uses the same design and (essentially) the same quality steel as the more expensive TOPS BOB and ESEE 4. The difference in price is due to a cheaper handle material and a brand that’s not quite as revered as the leaders. We also love its bigger brother for $15 more, the Becker BK2. The Gerber StrongArm and its popular serrated sibling, the Gerber LMF II, have recently emerged on the survival scene as killer budget blades. We picked the StrongArm Fine Edge because we don’t recommend serrations on a field knife blade.

Best overall:

Winkler Belt Knife

The $100 to $160 sweet spot is perfect for most people because modern metallurgy and manufacturing have created dependable knives at affordable prices — which means you get at least 80% of the performance you’d ever find in the top-shelf market.

Modern improvements also mean a step up into the >$200 class gives you a ridiculously-awesome knife that would beat >$600 custom knives of just 20 years ago. So with the caveat that recommending one knife over another in the upgrade category is like choosing between 90’s Michael Jordan and present-day Lebron James, our picks for overall best field knife are the Winkler Belt Knife and Spyderco Serrata.

The Winkler Belt Knife was first introduced to the popular imagination in SEAL Team 6 member Mark Owen’s account of the raid that killed Osama bin Laden. If you can afford the price of entry, you can’t get a more thoroughly field-tested, hard-use modern knife than a Winkler fixed blade. Spyderco is one of the top mass-production knifemakers in the US, and the Serrata is an amazing bit of engineering and design that checks all our boxes for a top survival knife. This knife is a joy to hold (the balance is perfect), and the stainless blade is made using a casting technique that creates microscopic serrations along the edge. So the edge always has a “bite” that makes it perfect for fibrous natural materials and game.

Be prepared. Don’t be a victim.

Want more great content and giveaways? Sign up for The Prepared’s free newsletter and get the best prepping content straight to your inbox. 1-2 emails a month, 0% spam.

- Check local knife laws

- The competition

- How preppers should use field knives

- Field knife 101

- Why full-tang, fixed-blade knives are best

- Picking the right blade length

- Picking the right blade type and shape

- Why you should avoid serrations

- Heat treatment is more important than steel type

- Don't worry too much about steel type

- Basic steel qualities

- Carbon vs. stainless steel

- Why we recommend stainless

- Selected steel profiles

- Composite steels

- Handle shape and material

- Blade edge grinds

- Sheaths

Why you should trust us

We’ve collectively spent decades in the knife world. Your primary guides, Jon Stokes and Tony Sculimbrene, have been professionally reviewing knives and outdoor equipment for years, including interviews with knife makers, special forces operators, professional guides, big game hunters, and other serious users of edge tools. We’re preppers, hunters, and bushcraft instructors who often hang around knife-enthusiast communities.

Knife laws

Knife laws vary quite widely by state and municipality. Even if your area is gun-friendly, don’t assume it’s also knife-friendly. Check your state’s knife laws, then Google for your local city/county (which can be more restrictive than your state).

The competition

Although our review spans experience with hundreds of knives, these are the top 30-40 choices on the market that fit our criteria. Did we miss something or it’s out of date? Let us know in the comments!

View the spreadsheet in Google Docs

How preppers (should) use field knives when SHTF

A field knife is used for more than just cutting things. But, like most prepping gear, there are tradeoffs — the more specialized a tool, the less often it will be helpful.

Remember one of the most important sane prepping rules: You can’t predict what’s going to happen, so don’t get tunnel vision. We see too many people make the mistake of ignoring 99% of likely needs by optimizing for their worst-case-scenario fantasy (like a bear attack).

Consider all the things our ancestors had to do on their own with only basic tools. Modern preppers face an even wider range of challenges, such as:

- Cooking

- Opening food containers

- Fishing or hunting and cleaning/prepping the meat

- Chopping small to medium pieces of wood, such as household furniture for a fire

- Making fire by drilling a notch in fire wood, scraping fuel off trees, striking a spark from a ferro rod, etc.

- Building shelter

- Digging holes, hammering anything that needs a smack, etc.

- Making tools and traps

- Prying open a door or container, breaking glass, and other entry/destruction

- Last-resort self defense against other humans, animals, or malnourished zombies

- Basic surgery and medical care, including removing clothes and objects

What you will not do with your knife:

- Throw it

- Hack your way through a thick jungle

- Chop down large trees

- Fight a bear

Knives are primarily for cutting and stabbing. Chopping is secondary.

There are differences between knives based on intended activity. One blade might be better at stabbing meat through layers of clothing or hide, for example, while another is better at precise surgical cuts or chopping wood.

Use vs. abuse

In daily life, it’s considered a grievous sin by knife enthusiasts to use a knife for things like digging a hole or prying open a door — but we of course want to plan for those needs in an emergency, so a good survival knife must be capable of occasional use and abuse.

The one exception here is knife throwing. You are not a ninja, nor will you play one in the apocalypse. Flinging the weapon that’s in your hand at a bad guy is really dumb, because then it will no longer be in your hand, and unless you’re extraordinarily lucky or skilled it will also not be in the bad guy. So don’t ever throw your knife.

The perfect pair: field knife and big blade

This guide recommends medium-sized blades, but there are some tasks where a large blade really shines, namely chopping and killing. This is why many cultures pair a standard-sized knife with a larger blade that can be used for one or both of those two purposes.

Lewis and Clark’s famous expedition classified hatchets as tools and big knives as weapons.

Sometimes the bigger blade in this combo is an axe (or hatchet, tomahawk, one of the Winkler axes carried by US Special Forces units, etc.), and sometimes it’s a bigger knife (or machete, leuku, bolo, kukri, seax, Bowie knife, etc.)

Note that the axe and large knife aren’t entirely interchangeable: an axe is a chopping tool that can readily be used as a weapon, and a large knife is a weapon that can be used as a chopping tool.

You can see this axe vs. big knife distinction in the way that Lewis and Clark put together their gear list for their famous expedition: hatchets were listed under “tools” and big knives were listed under “weapons.” Later, in the Civil War-era South, the Bowie knife was considered a sidearm, not a camping tool, and was eventually regulated as such.

We’ve encountered skepticism that US Special Forces soldiers actually carry axes and tomahawks into combat, and use them for breaching and fighting. But this fact has been reported in a number of mainstream outlets, and we have personally interviewed three different Navy SEALs and one knifemaker on this exact topic and can confirm that it’s true. The teams are very secretive about their gear, so it’s impossible to get anyone to go on-the-record about it. But know that it’s a real thing, and that the fixed-blade plus hatchet/tomahawk/axe combo lives on in modern warfare at the most elite levels.

Field knives for beginners

Belly: The 25% of the blade edge closest to the tip — similar to a chef’s knife, the belly area is used for fine slicing compared to blunt chopping closer to the handle.

Swedge: Also known as the “false edge,” this is a narrow part of the blade behind the tip on the spine side.

Spine: Most field knives have a straight spine, unadorned with serrations or filework. With a wide, flat, straight spine, you can hammer or create a fire spark. If the spine’s corners are rounded off (called “chamfering”), as they are on some custom and semi-custom designs, this can make it impossible to throw a spark from fire steel without using (and damaging) the edge.

Choil: A half-moon notch between the blade and the shank or guard. A finger choil is large enough for you to get your index finger into when you choke up on the blade for fine work (almost like a trigger finger on a gun). While it does give you better tip control, it sacrifices edge length and can easily get caught on something when chopping (to the point of injuring your arm/shoulder), especially when using a lanyard. A sharpening choil is a much smaller notch that makes the blade a bit easier to sharpen without cutting into the shank with your stone or strop.

Ricasso: The flat part of the blade between the bottom of the edge (or choil) and the start of the handle or guard. The ricasso usually features some markings identifying the blade’s maker and/or steel type.

Jimping: Small, flat serrations on a knife’s spine right above the handle. It’s the mirror opposite of a choil but with the same intent: Instead of using your index finger on the bottom for extra control, the jimping is an area on the top spine for your thumb.

Guard: Protects your fingers from sliding up onto the blade and from an opponent’s knife sliding down onto your wrist. Many field knives will forego a full-blown guard in favor of deep finger grooves and/or a bolster.

Bolster: The bolster is a common feature of kitchen knives, and it keeps the index finger of the user’s hand from sliding up the blade.

Handle: The handle is the part you grab and use to control the blade. On full-tang knives the handle can be two pieces sandwiched on each side of the metal core.

Pommel: The very bottom of the handle. Different shapes have different uses. Flat pommels are good for hammering, while other types are used for breaking glass, and so on.

Lanyard holes: Although it’s easy to ignore lanyards in outdoor gear, they can make a big difference when using your knife in the field (and may even save you a wrist injury!) Many of the pommels pictured above feature holes for a lanyard.

Full-tang, fixed-blade knives are best for prepping

Our recommendation, and the overwhelming consensus of the prepper and survival communities, is that a full-tang fixed-blade knife is ideal in the field survival knife role.

There are good times and places for foldables, but not as your primary BOB/GHB knife. None of the choices in this guide are folders.

Foldables (like many pocket knives) are nice when you want compactness and to protect the edge without an extra sheath.

However, folders come with a major drawback: durability. No matter how tough or expensive a folding knife is, it will always be less durable than a good fixed-blade. The place where the blade meets the handle has a pivot, and a pivot will always be mechanically weaker than a solid piece of metal.

Similarly, a full-tang knife — where the metal extends, unbroken, all the way from the tip to the pommel — is much more durable than the alternatives.

The smaller the tang, the less metal there is holding the blade to the grip portion of the knife and the weaker the blade-to-handle bond is. Knives with small, thin tangs are more prone to failure under lateral stress than knives with larger tangs.

It’s not a rare problem. We’ve seen countless cheap knives break apart where the blade meets the grip after just a few reasonable uses in the bush:

The downside of a full-tang knife is weight, and sometimes balance. All that metal in the handle can make the knife grip-heavy, and one way to fix this is to skeletonize the tang by machining holes into it (like Swiss cheese). Skeletonized tangs have most of the strength of full-tang knives, but without the weight.

Picking the right blade length

Unfortunately there aren’t commonly-used standards or terms for blade sizes. Roughly speaking:

- Small: below 3.5″

- Standard/Medium: 3.5″ to 5.5″

- Large: 5.5″ to 7″

- Extra Large: over 7″

The oversized knives carried by Sylvester Stallone in Rambo: First Blood and Rambo III were the definitive “survival knife” in the 1980s.

Sadly, like most things Hollywood, those large-sized knives are flashy and unrealistic — not anything a normal person would carry into a survival situation.

As much as we love the idea of big knives, the depressingly mundane reality is that the ideal blade length for a survival knife is somewhere between 3.5 and 5.5 inches. The vast majority of fixed-blade knives used by the world’s militaries and experienced bushcrafters are in this standard size range.

It boils down to ergonomics and the mechanics of leverage.

The bottom half of a knife blade (closest to the handle) is used for big cutting strokes, and the top half (the belly) is used for all the other things you use a knife for, like carving and slicing. The further away that blade belly is from your hand, the less control you’ll have over the part of the blade that you’re working with the most. Bringing the tip closer by shortening the blade gives you more leverage and control over this critical part of the knife, greatly reducing frustration and fatigue.

Although some survivalists love blades over six inches, we recommend avoiding it because it’s too big to be good at normal field knife stuff but too small to be good at tasks better handled by axes, hatchets, and jungle blades like machetes and kukris.

If you’re experienced enough in the bush to accommodate these tradeoffs, or just really want a big blade, check out our review of the best Bowie knives.

Picking the right blade type and shape

Knife blades come in many shapes, but we recommend sticking with these classics:

- Drop point

- Clip point

- Spear point

- Harpoon point

- Modern tanto

- Straight back

- Nessmuk

- Sheepsfoot / Wharncliffe

If it looks magical, it probably isn’t; and if it looks like something you’ve seen a million times before, it’s probably magical.

In other words: avoid the exotic and stick with the conventional. Knives have been around for thousands of years and every possible shape has been tried. It’s unlikely something new will beat the conventional until there’s a big leap forward in metallurgy.

There are commonly-used labels for different blade shapes, but they’re fluid, and often stretched and mangled on retail sites and in various buyer’s guides. You’ll see clip points categorized as spear points in some cases and as Bowies in others, and spear points categorized as drop points, and so on and so forth. Confusion abounds, so we do the best we can and try not to get too worked up over these divisions.

Drop point: We consider the drop point to be the default field knife blade shape, and the baseline against which others are judged. A drop point gives up a bit of belly vs. a straight-back design, but it still has plenty of belly to cut with. It also has a strong tip, but its tip isn’t as sharp as some of the other designs listed here, so it has less of the stabby.

Clip point: Close to and sometimes confused with a drop point because the shape is similar, but with a false edge (often called a “swedge”) on the downward-sloping part of the spine towards the tip. The swedge, which is typically not sharpened but can be if needed, trades away a bit of the regular drop point’s tip strength (i.e. the tip has less metal behind it) for increased stabbing effectiveness.

This added stabbing ability makes the clip point popular on fighting and “tactical” knives. It’s also popular on survival knives that are intended to do double duty as field and fighting knives.

The Bowie knife is a variant on the clip point, and in fact the two are often used interchangeably. The famous Bowie knife maker Bill Bagwell used to insist that a real Bowie knife had to have enough of a curve in the clipped part of the blade that it made a slight hook.

Spear point: A somewhat popular tactical knife shape, where the tip of the blade falls lower than the drop point/clip point. This shape is a little better at stabbing than a drop point blade but doesn’t have the tip-strength issues of a real clip point because there’s typically more metal behind the tip.

How far above the centerline a blade has to be before it goes from being a spear point to a drop point is a bit subjective, but the main thing is that the point is close to the center line and has substantial metal behind it all the way out to the edge. The famous Randall Model 18 is a classic spear point survival knife.

Harpoon point: Growing in popularity in the tactical knife world, the harpoon is essentially a clip point with more metal behind the tip, and thus more strength for stabbing and weight for chopping. These blades are good for both tactical applications and hunting.

Tanto: Refers to either the traditional Japanese-style tanto point, or the so-called “modern” tanto (or “American” tanto or “Western” tanto). Both are popular in tactical circles for their unmatched combination of tip strength and stabbing efficiency.

The traditional tanto is a particularly excellent design, with plenty of belly for slicing and a fast, strong tip for stabbing. The design makes for a great tactical knife that can do many field knife duties with the important exception of chopping; a classic tanto design is balanced toward the handle and is a terrible chopper. Most tantos fall into the medium and large categories, and most folks, if they’re going to carry a knife that long, want to be able to chop wood with it, hence the relative rarity of the classic tanto as a field knife.

Most tanto-style field knives sold in America will have the “modern” tanto blade shape, with its dual bevels and greater tip weight. This design is not as embarrassing to chop with, but sacrifices belly thanks to an odd point. These knives have incredible tip strength, but they’re not as good to work in wood and flesh with because that all-important belly has been compromised.

Straight back: A very traditional design that’s most often associated with kitchen cutlery, but it makes for a very good all-purpose blade shape, especially for game processing and general cutting chores.

This blade shape used to be much more popular with outdoorsmen than it is in the modern era — some traditional fixed-blades carried by early North American trappers have this shape. When the Bowie-style clip point and drop point began to take over in the age of industrial manufacturing, the straight back ended up relegated to the kitchen table.

There are some outstanding modern field knife examples of it out there, though, like the Case/Winkler collaboration and the ever-popular Mora.

Nessmuk: A bit of an odd-looking shape that originated with the 19th-century naturalist and outdoors writer George Washington Sears, who wrote under the pen name “Nessmuk.” This blade is designed primarily for slicing and skinning, i.e. game processing; it’s intended to be one part of the “Nessmuk trio” of blades, with the other two blades being a small, double-bit hatchet for wood processing and a folding knife for generalized cutting chores.

The classic design, per Sears’ specs, is supposed to be quite thin, making it unsuitable in the field knife role, but many of these blades from modern makers are as thick as any other field knife. You can find many variants on this blade shape, and over 100 years later it remains popular with outdoors types.

Sheepsfoot / Wharncliffe: There is a family of blade shapes where the spine curves sharply down to meet a relatively flat edge, and variants on these designs are starting to make a comeback in outdoors and tactical circles. You can read more about them in this excellent blog post, but basically these blades excel at two things: wood carving and killing.

This is our least-recommended blade shape for now, but that may change as these designs see more widespread use and become more popular with the outdoors set. One of our favorite field knives of recent years is the Southern Grind Jackal, which doesn’t really belong to this family but clearly takes some inspiration from it.

Avoid recurves and these shapes:

Trailing point: Very good for game and food preparation, since you get a ton of belly to slice with, but it falls down in the tip strength and stabbing departments.

Gut hook: The gut hook design is fantastic for game processing, but it’s just too specialized for a field knife.

Dagger: The dagger is purely a weapon and its totally unsuited for the field knife role. These blades do one thing really well: stabbing. As for slicing and chopping, they do the former poorly (they’re harder to control) and the latter not at all.

Recurve: A recurve blade has a slight “s” shape curve in its edge, and it’s more of a design feature than a blade shape because it can be combined with some of the other shapes above.

The curve gives more edge in the same tip-to-pommel length, which helps with longer cuts and gives added leverage when using the belly. These advantages make recurves popular in fighting knives, like the Walter Brend, and in some field knives, like the Case Winkler Recurve Utility that rides on one of The Prepared’s expert’s belt when in the woods.

But recurves have a major disadvantage in that they’re tricky to sharpen. Sharpening a knife is a skill that takes a bit of practice, and the recurve just compounds the difficulty. Nonetheless, if a user is dedicated enough to learn how to maintain its edge, a recurve can be a useful addition to a knife design.

Avoid serrations

We are not fans of serrations on field knife blades — either on the spine or on the cutting edge.

When serrations are placed on the spine, they create stress risers and weaken the blade; when they’re on the edge, they’re difficult to sharpen, especially in the field without specialized tools.

Note that serrated blades do have their place in disaster preparedness because they’re designed for quickly cutting fibrous material: rope, seat belts, straps, and wood and plant matter. This is why it’s a good idea to carry a saw or a multi-tool as part of your kit, so that you get the benefit of this type of blade without adding a specialized, performance-reducing feature to your field knife.

Heat treatment trumps blade material

A perfect example of why you shouldn’t get too worried about internet debates: Serious steel junkies know that heat treatment is more important than steel type, every time, even though it’s discussed far less often.

Heat treatment is the process of heating up a metal and then cooling it in a controlled manner in order to change its structure and harden it in just the right way.

Most custom knifemakers closely guard their heat treatment protocols, since that’s often what sets their blades apart from all the other makers using the same steel from the same manufacturer.

That’s why buying a knife from a proven maker is so important; don’t buy a blade from a maker you don’t trust, regardless of the steel that’s advertised.

There are a number of makers who have become famous for their ability to heat treat certain steels to the point that they have unrivaled combinations of toughness, edge retention, and hardness. For example, Bob Dozier’s D2 steel is famous, as is Barry Dawson’s 420C. Buck’s new 420HC is getting rave reviews, and it compares favorably to some far more expensive steels. Some famous “proprietary” steels, like Busse Combat’s INFI and Swamp Rat Knife Works’ SR101, are really production steels with a complex, secret heat treatment protocol.

Heat treatment has a bigger impact on the relative performance of older steels than on newer ones. The older steels have been around long enough for some makers to discover the secret to making them really shine, whereas with newer steels everyone is on a more equal footing. So if you’re picking a knife with an older steel, the maker matters a lot more than if you get one of the new super steels.

Also, beware of brands that have been credibly accused of advertising one steel but selling another. Most users have no way of really knowing if they got the steel they paid for, so we rely on reports via knife enthusiast sites like BladeForums.

Don’t worry too much about picking the right blade steel

The most exciting thing about modern knives is how far we’ve come with metallurgy. New metals seem to come to market every year, creating a paradise of options for knife nerds.

Which inevitably leads to endless internet debates about this metal versus that metal. Learn these basics and why experts recommend what they do, but ignore the rest of the noise.

Note that many of the knife models recommended in this guide are offered in a variety of steels, so if you find a knife you like then you can often get it in a steel that’s tailored to your particular needs.

Steel qualities

Hardness: Measured on the Rockwell scale, where higher numbers denote harder steels. In general, harder is better, because a harder blade will hold its edge longer. The downside of hardness, though, is that harder blades are also more brittle, which brings us to our next quality…

Toughness: The ability of a knife to withstand stress without breaking. The tougher the knife, the less likely it is to fail under lateral stress (e.g. prying) or get pieces chipped out of its edge when chopping. Ideally, you want an edge that folds over under stress instead of chipping, because you can always straighten a folded edge back out but you can’t restore metal to a chipped edge.

Corrosion resistance: This is the knife’s ability to withstand the elements without rusting and pitting. For knife buyers who care about aesthetics and maintaining a factory-fresh look even after use (i.e. not folks in the market for a survival knife), whether a knife forms a patina when exposed to acidic substances found in foods also falls under this heading.

Wear resistance: The more cuts you can make with a knife without the edge going dull due to friction-induced loss of metal, the more wear resistant the blade is said to be. Note that this property is sometimes overrated, because most dulling is due not to wear but to microscopic bending and chipping. Depending on the hardness of the steel, wear resistance can mean more difficulty in sharpening, because it’s harder to remove metal and reshape the edge.

Edge retention: How long the knife holds an edge when doing what it’s meant to do. For a cutting knife, edge retention is measured by how many cuts it can make before dulling, and for a chopper, it’s how much chopping it can do. Because different edge profiles dull in different ways under different circumstances, this quality isn’t always as directly correlated to wear resistance and ease of sharpening as many assume.

Ease of sharpening: Because blades can be dulled by chipping, folding, or wear, ease of sharpening is a catch-all concept that refers not so much to the steel but to how easy it is to restore the edge on a finished blade. If a blade’s edge is worn down or chipped, then you’ll need to remove some metal in order to sharpen it; in such cases, steels with less wear resistance are much easier to work with. If an edge folds to the side then you’ll need to straighten it back out, in which case wear resistance actually helps with ease of sharpening because it allows you to restore the edge via friction without removing metal.

Carbon vs. stainless in survival scenarios

Carbon steels are the traditional choice with a number of benefits:

- Harder

- Tougher

- Better edge retention

- Better wear resistance

- Easier to sharpen

So why not just go with carbon steel every time?

Carbons have poor corrosion resistance, which is a really big deal in a field knife that will be exposed to the elements. In fact, as a general and frustrating rule, the more of the aforementioned beneficial qualities a steel has, the faster it corrodes.

Why, Knife Gods, why?!?

If you’re carrying a knife in the wild, under all sorts of adverse conditions, you won’t always be able to keep it clean, dry, and oiled. Rust can show up in just a few hours under the right conditions, and even a little bit of rust can pit the edge of a knife and require some metal removal to restore sharpness.

Stainless steels were originally developed for applications like food preparation and medicine, where near-constant exposure to moisture, salt, and acids are unavoidable in the normal course of use. Such stainless steels require very little maintenance to prevent rust.

Stainless steels are far more brittle than carbon steels, and if hardened too much they’ll easily chip when used for chopping or crack when used for prying.

Over the past few decades, as metallurgy has advanced, carbon and stainless have traded places a few times as the most commonly recommended steel families for survival knives.

When stainless was first introduced, it was just too brittle at the hardness levels needed for cutlery applications to be worth consideration in a field knife, so carbon steel continued to rule the day. Much tougher stainless steels were eventually introduced that were a better fit for outdoors knives, and some were even wrapped around carbon steel cores to make stainless knives that could stand up to heavy impact and lateral stresses.

Recently, carbon has come back in a big way on the knife scene. A number of high-carbon super steels have emerged in the market at the same time as innovative anti-corrosion coatings. High-carbon knives now come coated with ceramic-based coatings like Cerakote, high-tech diamond-like carbon (DLC) coatings, or controlled oxidation layers.

Such blades promise the best of both worlds: The toughness and edge retention of carbon with the corrosion resistance of stainless.

These coatings are an important innovation, but they are not without drawbacks. First, the coating doesn’t extend to the edge of the blade, so you can still lose part of an edge to corrosion fairly quickly. Second, coatings can and will come off, either through field use or by accident in the course of sharpening. Finally, most coatings will keep the spine of a blade from throwing a spark on a ferro rod, which limits the knife’s use in fieldcraft.

We recommend stainless steel (if you can afford it)

We generally recommend using high-quality stainless blades because emergencies are unpredictable and you’ll likely be abusing your knife. It’s easy to imagine using your knife, it gets damp, you throw it back in the sheath/bag, and you forget about it while dealing with more pressing matters. Who wants to carry oil in their emergency kits?

With proper heat treatment, modern stainless blades are ridiculously tough and corrosion resistant. We’ve done knife reviews in the past that surprised us at just how tough these modern stainless products can be.

Of course, there’s a caveat: A high-end stainless steel blade tends to be more expensive than carbon steel blades of comparable quality.

The high cost of good stainless is the reason why, despite our preference for stainless in a field knife, many of our general knife recommendations here are carbon steel. Carbon steel is a lot cheaper to work with, and it’s far more forgiving than the super stainlesses when it comes to heat treating, so for lower-cost production knives, carbon is where it’s at.

Selected steel profiles

Specific steel types are yet another example of qualities that knife nerds will argue over. We’ve done the hard work for you in our recommendations, but in case you want to get a sense of what’s out there…

Carbon

1095: This is a tried-and-true carbon steel that has stood the test of time. It can’t stand up to some of the super steels out there, but it’s hard to beat for the price. Note that not all 1095s are equal (e.g. 1095 Cro-Van is better), but going deeper is too much for this review.

W2: Another standby, like 1095 but with even more carbon, which means more toughness and less rust resistance.

5160: A popular high-carbon steel that’s extremely tough, and finds some use in saw blades and production knives. A very good steel, but it’s not at all corrosion resistant so you’ll typically see it coated.

D2: One of the nicer tool steels to come along, with high corrosion resistance for a carbon steel. It’s also quite tough, and when combined with the right heat treatment it’s hard to beat.

O1: Another tool steel that’s popular on high-end production and custom knives. It’s known for good edge retention and poor corrosion resistance.

A2: A favorite for large knives, especially heavy choppers, due to its extreme toughness and impact resistance. It’s typically coated because it rusts quickly.

80CrV2: One of the hot new kids on the block, this is a high-carbon steel that’s relatively inexpensive and extremely tough, with good edge retention and ease of sharpening. Currently Daniel Winkler and Barry Dawson, two of our favorite hard-use field knife makers, are using this in their mid-tech knives. Winkler coats his blades with a cold Caswell finish that provides rust protection but leaves the ability to throw a good spark on a ferro rod, and Dawson is using Cerakote.

M4: This extremely tough, wear-resistant steel holds a wicked edge. It’s also fairly corrosion resistance for a non-stainless, so you’ll sometimes see it uncoated. M4 is a beast to sharpen, though, so it’s best left to big choppers.

S7: A very high impact resistance steel popular for axes and search-and-rescue (SAR) knives because of its ability to take a literal beating. Winkler Knives is using it on some of their specialty axes and knives intended for demolition and forced entry. It doesn’t get as hard as some of the other steels, though, so you don’t quite get the edge retention of some other options.

CPM 3V: One of our current favorite super steels. Insanely tough, can be hardened to high levels, and is relatively corrosion resistant. Holds an edge for forever with the right heat treatment. It’s also expensive and very difficult to sharpen, so it’s iffy as a survival knife steel because we’d never want to have to redo a 3V edge in the field.

INFI: A proprietary steel used by Busse Combat, INFI combines good edge retention and superior toughness with ease of resharpening and excellent corrosion resistance. In terms of its composition, it’s close to D2, but Busse uses a proprietary heat treatment protocol to get the most out of it.

Stainless

420C (and HC): An old-school stainless that doesn’t get much love in the era of super steels, but its relatively high carbon content (for a stainless) adds toughness and edge retention. In its high-carbon flavor (420HC) those properties are improved further, at the expense of some corrosion resistance.

154CM: A high-quality stainless that was very popular in the 80’s for its combination of toughness and corrosion resistance. Knifemakers are still making great knives with it, and it’s relatively common, but it has since been improved upon by many of the newer steels.

ATS-34: The Japanese version of 154CM; the degree of difference between the two is debated.

ZDP-189: Japanese super steel that’s extremely hard and popular mainly for folding knives. It’s not as tough as some of the other stainlesses listed here — especially in terms of impact resistance — so you have to be careful about picking this for a field knife choice.

VG10: One of the earliest stainless super steels to become popular for larger field knives, VG10 is still a top performer — especially when it’s used as the stainless component in a laminate blade (see below). It’s very corrosion resistant and easy to resharpen, and it holds an edge forever.

S30V: Designed with input from Chris Reeve, S30V is one of the most important and well-loved stainless super steels of the past decade. This is a premium, fully modern stainless with very good toughness, edge retention, and corrosion resistance. Like the other stainlesses listed here, except for 420 and 154CM, it’s expensive.

Elmax: Stainless super steel that’s considered an improvement on S30V in the areas of toughness and edge retention. This is one of the best, most popular “big knife” stainlesses on the market right now.

S35VN: Another steel designed as an upgrade to S30V, this steel adds quite a bit of toughness and corrosion resistance vs. some of the other steels listed, here. If you can afford to go with either this or Elmax, then that may be the best possible choice right now for a stainless field knife blade.

Composite steels

Sometimes it’s not always possible to get all of the qualities you want in a single steel, so many makers offer blades in composite steels.

In most cases, like Fallkniven’s VG10 and Cold Steel’s San Mai, these are stainless steels wrapped around non-stainless cores, so that the resulting blade has the corrosion resistance of stainless and the stress resistance of the underlying carbon steel.

Composite steels are also used for visual effect, as with modern Damascus steels. In general, modern, pattern-welded Damascus gives up some performance characteristics in exchange for appearances. Because of this tradeoff, we do not recommend Damascus for a field knife.

Handle shape and materials

Handle shape can make a big difference in how well you use a knife, especially on long days. While it’s a personal “fit” opinion, we generally prefer shaped handles (like a Coke bottle curve) over the straight-as-an-arrow types.

There are a near infinite variety of handle materials to choose from. We recommend:

Canvas micarta: Our favorite handle material for a field knife. It’s nigh indestructible, not too heavy, and provides plenty of solid grip if it’s textured properly. Micarta famously keeps much of its grip even when it’s wet or bloody.

G10: Our other favorite handle material, G10 is a synthetic that has similar properties to canvas micarta, but some think it looks nicer.

Thermoplastics: Many makers have their own house names for the injection molded thermoplastics used in their handles, but despite the different names these often have similar characteristics. These materials are typically low-cost, lightweight, strong, temperature- and chemical-resistant, and all-around satisfactory for field knife use.

Wood: Many types of wood, both stabilized and untreated, make for wonderful, durable field knife handles. In most cases, you sacrifice a bit of durability when you go with wood over a synthetic, but not always (ironwood is almost as tough as any synthetic) and often not much, and not in a way that matters if you aren’t totally abusing the knife by throwing it or trying to break the handle. Many folks love the feel and grip of wood, so if you’re partial to this time-tested material then know that it can absolutely hang with the latest and greatest synthetics for general purpose field knife use.

Leather: We don’t recommend stacked leather for a field knife handle, but we don’t insist you avoid it, either. A good stacked-leather handle is a joy to use, relatively lightweight, and when dry the grip and feel are amazing. But as with all things leather, moisture is the enemy, so you’ll need to take care to keep the rings treated (we recommend Obenauf’s LP) and dry. Also know that leather can be stained by blood or chemicals, and it gets slippery when wet.

Blade grinds

A blade’s “grind” refers to its cross-sectional shape; i.e. how the metal comes together to form the sharp cutting edge:

Nearly all blades in modern production knives have what’s often called a “compound grind” or “double bevel,” meaning the bulk of the blade is ground a certain way, and then the very edge itself has its own grind (either a V grind or a convex grind).

There are a few popular blade styles that are not double bevel. You’ll typically see the “full” prefix on those grinds, such as the full-convex Fallkniven F1. Or, we could also say that on a full-convex blade, both the blade and edge grinds are convex.

Full convex grind (i.e. convex blade grind with a seamless convex edge): Our top recommendation for a field knife because it chops really well, and also slices and stabs well enough that you won’t miss a thinner grind. Convex blades are also extremely durable, because there’s so much metal behind the edge.

Unfortunately, convex grinds and edges have a totally undeserved reputation as difficult to sharpen. You can easily sharpen a convex grind with a leather or cloth strop (especially one loaded with sharpening compound), or with a mouse pad and some wet/dry sandpaper.

Because the edge is curved, this grind is very forgiving if you accidentally make a few strokes while holding the knife at too low or too high an angle.

A highly polished convex edge will be stronger, longer lasting, and easier to maintain in the field than the kind of ragged V-grind edge you’ll get from a sharpening stone.

Flat grind: If you don’t pick a knife with a full convex grind, the next best thing is to pick a flat grind — especially a sturdy “high flat” grind (also called a “saber grind”) — and convex the edge on a strop. This will get you pretty close to a full convex blade, but with better slicing abilities (thanks to the thinner edge) and slightly worse chopping abilities.

Scandi grind: If you go with a V-grind, you might as well make it one that’s easy to sharpen. The Scandi grind is popular with bushcrafters because the “V” is very large and you can just press that flat against the stone and refine the edge.

The Scandi is stronger than the full-flat grind because there’s more metal in the main body of the blade. This combination of strength and ease of sharpening has made it a very popular field knife grind.

Hollow grind: Of all the grinds on this list, the hollow grind is the best at slicing. This blade grind has very little metal behind the edge, so it’s structurally weak and a terrible chopper, but it can push through flesh better than any of the grinds listed. This makes it a good fit for tactical and kitchen applications, but not as good for the full range of field knife uses.

You can make a high-quality hollow-ground blade work as a field knife — we’ve done it — but you have to be careful with it and understand its limitations.

Sheath considerations

A good sheath is an important yet often overlooked part of a knife purchase. But first-time knife buyers should be prepared for the sad reality that knife nuts know all too well: factory sheaths are usually not very good.

Knife sheaths come in three main materials: plastic (including Kydex and similar), leather, and nylon.

For cost and durability, you can’t beat plastic. So if you don’t want to spring for an aftermarket sheath, look for a knife that comes with a plastic sheath.

Factory leather sheaths are almost always terrible, even on relatively high end knives. In fact, it’s often the case that high-end knifemakers assume you’ll be buying an aftermarket sheath, so if they even include a sheath at all it’s often worse than what you’d get with a much cheaper blade. So if you have an option, pick plastic over leather for a production knife, and if you don’t, be prepared to invest in an aftermarket sheath.

Nylon is the worse of these three options by far. It’s noisy, unsafe, scratches your knife blade, and will fail when you need it most. If you end up with a nylon sheath, your first order of business is finding a Kydex or leather replacement for it.