Picking the best survival backpack is often more challenging than picking most of the stuff that goes inside the bag.

Even when you set aside personal preferences like fit and color, there are tons of considerations that matter in an emergency context: what kind of organizational layout is best for common gear, how well does a bag balance blending in vs. tactical features, weight vs. durability, and so on.

More: Bug out bag checklist and first aid kit checklist

To make matters worse, the market is flooded with options. It’s so easy for companies to make small changes that they can crank out a ton of different models, see what works, and iterate. And since everyone has their own personal quirks when it comes to backpacks, companies rise to meet the demand for so many fragmented choices.

Even in the course of writing the original draft of this guide, between the time we started collecting bags and publication, manufacturers would change things up too quickly for us to keep track.

So this is more of a purchasing guide to help you zero in on the right companies and products, rather than a contest where we pick the single best bug out bag backpack.

There’s a lot of theory down the page — so you can learn and be a better shopper at any time — plus recommendations for popular brands and specific bags we think fit the criteria.

In addition to hands-on reviewing, every bag tested was packed according to our recommended loadout so we could see how well it held common gear. The gear in this kit is pretty close to what we used.

The most important tips, whether you’re considering repurposing a bag you already own or shopping for a new one:

- Two-strap backpacks are the only acceptable type of bag in this role.

- There are no bags we recommend with new MSRP prices under $70 — the quality just isn’t good enough.

- The sweet spot for most people tends to be in the $125-$300 range.

- If you’re on a tight budget, it’s better to buy a better but gently-used bag than a cheaper new one. Check your local craigslist.

- Most people end up with a bag in the 40-55 liter range (2,450-3,350 cubic inches). For the vast majority, over 65L is unnecessary and under 35L is too limiting.

- If you don’t know the size of a bag you already own, try to stuff it with blankets/pillows and measure the outside dimensions. Then multiply for a rough idea of cubic inches, eg. 9” x 14” x 22” = 2,772.

- Backpack fit matters a lot — stop by a local sporting goods store if you want help figuring out your size.

- Have a rough understanding of what you plan to put inside and outside the bag. eg. Are you building a small evacuation bag or a full SHTF bag?

- The best type of bags tend to be mild versions of technical or tactical bags, ie. not too extreme in either direction.

- People who favor comfort and blending in tend to favor more technical bags, while people who value durability and customization tend to lean more tactical.

- You want your bag to blend in regardless of type, so avoid camo, bright colors, too much MOLLE/PALS webbing, etc. and consider the norms around you.

- You want a balanced mix of large main compartments, smaller interior pockets, and external pockets. Only 1-2 large compartments (and nothing else) or lots of smaller specialized compartments are bad.

- Front-loading bags (ie. “panel loaders”) and hybrid types with multiple access points are much better than top-only loaders that require you to dig everything out to get to what you’re looking for.

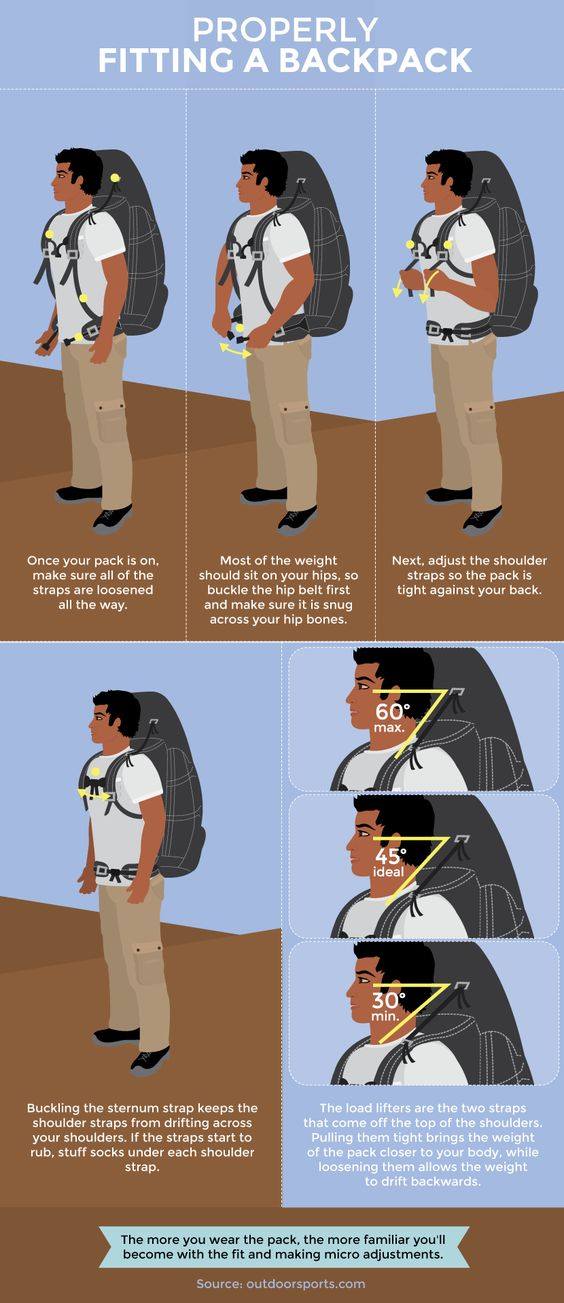

- Any bag over 30-35L should have a hip belt because you shouldn’t carry heavy loads just on your shoulders.

Contribute! Comment with bags you’ve tried and what you thought. We’ll update this list over time.

Best budget backpacks (< $125)

< 35L:

- Blackhawk 3-Day Assault Pack (32L) (Amazon)

- 5.11 Tactical Backpack – Rush 12 2.0 (24L)

35-45L:

45-55L:

- LA Police Gear Atlas 24 Hour Tactical (52L)

- Teton Scout (55L) (Amazon)

> 55L:

- Teton Scout (65L) (Amazon)

- LA Police Gear Atlas 72 Hour Tactical (70L)

Best mid-tier backpacks ($125-$300)

< 35L:

- 5.11 All Hazards Prime (29L) (Amazon)

- Deuter Trail Pro 33

- Eberlestock F5 Switchblade (28L) (Amazon)

- Mystery Ranch Scree (33L)

35-45L:

- 5.11 AMP72 (40L) (Discontinued – Can Be Found Used)

- Maxpedition Gyrfalcon (36L)

- Tasmanian Tiger Mission Pack Mk II (37L) (Amazon)

45-55L:

- 5.11 RUSH72 2.0 (55L) (Amazon)

- Deuter Women’s Futura Air Trek 45 + 10 SL (55L) (Amazon)

- Kelty Redwing 50 (Amazon)

- Osprey Farpoint Travel Pack 55

- Tactical Tailor Three Day Assault Pack – Gen 2 (51L)

> 55L:

- Gregory Baltoro 65 (REI)

- Deuter Aircontact Core 60 + 10 SL Women’s & 65 + 10 Men’s (REI)

- REI Traverse 60L Women’s

Best premium backpacks (> $300)

< 35L:

- Eberlestock F3M Halftrack (35L)

- Mystery Ranch 3 Day Assault (30L)

35-45L:

- Goruck GR2 (40L)

- Mystery Ranch Komodo Dragon (38L)

45-55L:

- Goruck GR3 (45L)

- Hill People Gear Aston 3 (40L)

- Kifaru 357 Mag (55L)

- Mystery Ranch Terraframe 3-Zip 50

- Tasmanian Tiger Modular Pack 45 Plus (Amazon)

> 55L:

- Tactical Tailor MALICE 2 or MALICE 3 (100L)

- Osprey Ariel 65 (Women’s) & Aether 65 (Men’s)

Why you can trust this review

Besides decades of combined experience as preparedness teachers and outdoor product reviewers, we have 10+ years of experience living out of backpacks for long stretches of time in the military and while traveling, including in places like North Korea and Iraq.

We’ve interviewed various backpack experts, including designers and product managers at top manufacturers, bag repair shops, outfitters, and SERE instructors.

With over 150 hours of total work: We researched and built a spreadsheet of over 500 bags to narrow down the top ~100 for deeper evaluation.

Be prepared. Don’t be a victim.

Want more great content and giveaways? Sign up for The Prepared’s free newsletter and get the best prepping content straight to your inbox. 1-2 emails a month, 0% spam.

Backpacks are best for survival

The whole point of a primary bug out bag is to be able to survive on foot. Which means you’ll have at least 20-40 pounds of gear that you need to be able to carry over unpredictable terrain and distances — possibly more if you pick up stuff along the way (eg. water or food).

The best way to do that is the humble backpack.

One of the main reasons this method has stood the test of time is that your hips are the best part of your body to hold weight without constant muscle activation. And the best way to hold weight on your hips is a fanny pack backpack.

Price tiers and brands

Within the realm of backpacks that are relevant to prepping (ie. excluding things like a basic school backpack), the new market generally breaks down this way:

- Under $75: Not good enough to depend on

- $75-$125: There are winners, but they’re hard to find

- $125-$300: Middle of the bell curve, most common

- $300-$500: Premium, worthwhile step up in quality

- Over $500: A few winners, but mostly starting to pay for the brand name

Although some brands will have products across a wide price range, you can generally sort common companies by tier.

Budget brands:

- 3V Gear

- Condor

- Explorer

- Fox Outdoor

- Jansport

- LA Police Gear

- Leapers UTG

- Rothco

- Sandpiper of California

- Voodoo Tactical

- “mystery meat” brands you find at stores like Walmart

Mid-tier brands:

- 5.11

- Deuter

- Gregory

- Keltyz

- LL Bean

- London Bridge Trading

- Maxpedition

- North Face

- Osprey

- Patagonia

- REI

- SOG

- Spec-Ops

- Triple Aught Design

- Vertx

Premium brands:

What you get when you spend more

Backpacks are definitely one of those “you get what you pay for” categories — although you start seeing diminishing returns for each extra dollar once you go over $400 or so, depending on the brand name.

The biggest areas where you’ll see differences based on what you spend:

- General build quality, durability, and lifespan

- Warranties and customer service

- Stitching

- Zippers and buckles

- Materials

- Water and tear resistance

- Ergonomics

- More personalized fit adjustment

- Adaptability and custom configurations

- Made in the US/EU vs. made in China/Mexico

Cheaper bags mean companies have less margin to invest in other things like proper customer service, warranty, and build quality. Osprey, for example, is famous for their comprehensive any-reason lifetime warranty. Random Chinese knockoff brands who only sell on Amazon/eBay might not be around in three years, and even if they are, they won’t care about you. Be skeptical if a brand doesn’t have their own dedicated website and support contact.

Cheaper bags will either skip hip belts entirely or include a bare-minimum strip of thin fabric. Similarly, cheaper bags will cut corners on the padding in shoulder straps, again sometimes having nothing more than a thin strip and/or using low-quality cushions that deflate quickly. Premium brands invest in higher-quality cushion materials that will still be springy years from now.

One of the most common problems with cheap bags is poor stitching that falls apart from stress. When evaluating a bag, look at how serious the stitching is around those critical seams and joints. Premium bags will also vary the angle of the doubled and tripled stitching to better hold against forces coming from different angles.

Another common way companies save money is by chain stitching the zippers. Which becomes a problem is one part of that chain breaks, which can pull apart the entire length of the zipper.

Budget brands cut costs through cheaper zippers and buckles. You may not notice the difference at first, but since these are the biggest wear parts, you will as you use the bag more. The zipper should feel substantial, smooth, and solid with no hiccups or snags, no matter what speed you use.

According to expert Luke Fowler, who repairs bags and helps companies like Triple Aught Design create better ones, one of the easiest ways to tell a cheap bag from a quality one is if they have branded zippers (usually “YKK”, the most famous zipper maker).

Premium bags will be more thoughtful with zipper design and placement, too. We love bags with four zippers on the main compartment because you can open little access holes wherever you need them, such as slinging a bag around on one shoulder and accessing from the side while on the move.

Intelligent designers will put zippers in areas less likely to be directly hit with rain — such as not having any zippers that face straight upward — since the zipper and seams around it are the most common entry point for water.

Besides using better materials that won’t fall apart, more expensive buckles are also easier to use. We particularly like the “Osprey-style” adjustment buckles where you pull the tail end of the strap forward / away from your body to tighten the hip belt, which is a much easier motion than trying to pull the tail end backward past your hips.

The higher price tier you buy, the more likely the bag has been intelligently designed for customization. Many brands will also offer in-house pouches and other adaptable gear as part of an overall system.

More expensive packs have attachment points so you can add/remove complimentary packs, which can serve as extra storage when attached or as smaller day packs when you want to leave the big bag behind on a scout. Higher-tier brands often make compatible accessories for their bags so you can kit it out Gucci-like.

If you’re on a tight budget

The backpack might seem like a good place to save a few bucks — especially since the stuff that goes inside the bag will cost at least a few hundred dollars.

But if you are depending on a backpack to survive, that means things are bad and you don’t want the single container that carries all of your critical stuff to fall apart when you need it most — and cheap backpacks will fall apart.

We wish there were no-brainer options under $75, but there just aren’t.

Tips on saving money:

- You can find high-end packs that are used and significantly discounted, but because they’re a premium product, they’re often still more than fine for a bug out bag. Many enthusiasts will upgrade their bags every few years then sell their still-great outgoing model on Craigslist, Facebook Market, local swap meets, etc.

- Buy after the end of a season, whether it’s back to school season, hunting season, etc.

- If you live in an area where outdoor recreation is popular, there may even be physical stores for second-hand gear or repair shops with leads.

- Check your local Play It Again Sports and Goodwill.

Size and shape

To keep things easy and consistent, we think about bag sizes in tandem with our bug out bag checklist, which is broken down into three prioritized levels depending on how big/advanced you want to get with your kit.

Using the gear in that list, we’ve packed the various levels into dozens of bags to figure out what sizes fit what levels. Roughly speaking — design can make a big difference here — minimum bag sizes for able-bodied adults are:

- Level 1 > 25 liters

- Level 2 > 45 liters

- Level 3 > 50 liters

Most of you should end up with a bag in the 45-55 liter range — the size of common airplane carry-ons — which is enough to carry the most popular and critical supplies without overloading, assuming one or two of the bigger items like a sleeping pad are strapped to the outside.

Size considerations:

- One of the most common mistakes we see is going too big. Do not buy a bag over 65 liters unless you already have backpacking experience with those loads.

- You can get a basic kit into small 25-35 liter bags, but frankly we’d never personally use a bag smaller than ~35L. Although smaller bags are obviously easier to carry and blend in better, you probably want some extra volume in your bag so you can add supplies that you find during an emergency.

- If you do go under 35L, then it should be a very “gray man” bag because that’s one of the main reasons to sacrifice and go small.

- If you live in colder climates, you need a little more room for bulky insulated clothing.

- Most people fill the space they have, which can lead to overpacking. Be disciplined.

- Even though our gear list adds 10 pounds of bulky gear from Level 2 to 3, the bag size doesn’t need to get proportionally bigger because some of that advanced gear gets strapped to the outside of a pack (eg. a tent or sleeping pad).

- How a bag is designed makes a big difference in these rules of thumb. For example, some 60 liter bags couldn’t hold the exact same gear we got into other 50 liter packs simply due to organizational layout.

You’ll often see bags labeled as 24 hour, 72 hour, 3-day assault, etc. This is branding shorthand for roughly how large they are for a common three day loadout in a military context. Similarly, labels like “assault pack” generally mean the one backpack a soldier would take with them on a three-day mission, which is a decent proxy for the kind of loadout you’ll have in your BOB.

But those labels don’t mean much in the end, are not standardized, and can trick you. For example, even though both bags have the “24” branding in the name, LA Police Gear’s 24 hour pack is 52L while the 5.11 Rush24 is 37L.

Shape considerations:

- Stick with basic box or tube shapes. Pyramids, ovals, and other designs sacrifice too much storage space.

- You generally want the fully-loaded pack to fit within the area between your shoulders, neck, and hips. It shouldn’t stick way out in any direction.

- Go too tall and you won’t be able to tilt your head back, or it’ll snag on stuff along the way.

- Go too wide and you’ll snag, have trouble getting in vehicles, through crowds, etc.

- Bags that are too deep — where they stick out far away from your back — don’t carry loads as well because the center of gravity is pulled away from your body.

- We love bags that can stand upright on their own on a flat floor. Avoid curvy bottoms.

Importance of fit for your bug out backpack

A backpack works best when it can direct the force of weight to the right spots and in the right proportions (eg. at least 60% on your hips).

But since your body is different than mine — even if we’re both generally a Medium — how a bag sits on the top of my hip bone or curves with my shoulders could be very different than yours.

The better the bag fits on your body, the more weight you can carry for longer and further. That might really matter in an emergency.

Which means pack fit is just as important of a criteria as any other. If you’re deciding between bag A and B, and A is overall slightly more awesome or cheaper but doesn’t fit as well as B, go with B.

Tip: Like buying shoes, sometimes you just won’t know until you try it on. Almost all ecommerce vendors will let you return a bag you bought online, but if you want to save yourself that step, pop into a local outdoor store and try some on. Employees in bag departments at stores like REI and Cabellas are trained to help you find the right fit (just like good shoe salespeople). Be sure there’s some weight in the bag when you do — they often have sandbags near by just for that.

Cheaper or smaller backpacks tend to have more universal sizing (and a lack of fine-tuning customization features) since the designers assume the bag will have lighter loads and only be used for short bursts.

Larger or higher-quality bags tend to include more of those fine-tuning features, such as adjustable spine heights or sternum straps with vertical adjustments.

Women’s survival backpacks

Unless a bag is specifically labeled with a gender, you should assume it’s unisex or cut for men.

Some women don’t care. Others do. Roughly speaking, the curvier and/or bustier you are, the less comfortable a non-female bag will be.

One of the most common areas where companies tweak designs for women is in the shoulder and sternum strap. Designers assume women have narrower shoulders and wider hips than men of the same general size, for example. The straps themselves will also have different curves or positions to accommodate bras and breasts.

A growing number of companies are adding dedicated Women’s versions to their product lines. Sometimes they’ll keep the same model name and add “- Women” to the end, such as the Kelty Coyote. Sometimes they make slightly different model names, such as Osprey’s similar Ather for men and Ariel for women.

The most popular brands for women’s backpacks:

Internal vs. external frame

Backpacks need a rigid frame in order to properly direct weight to the right spots. Without a frame, a backpack has no built-in form and hangs like an empty sack.

Most people end up with an internal frame, which means the structure is either sewn into the fabric and/or has removable inserts (ie. “stays”) stored in the interior (usually a fabric compartment along the spine). Just look around your local store and you’ll likely find 10-20 internal frame models for every external frame.

Stick with internal unless you know you have a specific reason to use externals and/or are already comfortable with them through time in the military.

Pros and cons:

- External frames are often a separate piece you need to buy and combine. Besides extra cost, this adds the complexity of matching bags and frames — and manufacturers don’t always make it easy to figure that out.

- External frames are generally more rigid than internals, which means they can carry weight more comfortably (especially heavy loads). The famous ALICE pack used in the military is a great example.

- Internal packs tend to move better with your body when you’re moving in ways other than just normal standing/walking.

- Internal packs are typically lighter.

- Some external frames act as a customization platform, giving you more room to tweak things your way. For example, some have “shelf space” between the frame and fabric bag where you can carry an ammo can, water jug, or game carcass.

- External packs have more airflow around your back because the frame holds the pack an inch or so out.

- Some external frames even have a flip-down seat built in — picture the seats people bring and lay on top of benches at sports games or concerts — so you can have a place to rest against the weight of your pack while waiting in hours-long refugee lines and so on.

Types: tactical vs. technical vs. travel/EDC

Very few manufacturers make bags specifically marketed for emergency preparedness. Which means you’re usually shopping among these categories:

- Technical bags are what you’d find at a sporting goods store or on a hiking trail

- Tactical bags are built for military and law enforcement scenarios

- Travel bags cover a range from everyday carry to “backpacking through Europe”

Technical and tactical bags are usually better than travel bags because the latter, while great for blending in and EDC/travel, often don’t add any other value as a bug out backpack over the former. The travel bag category is evolving more quickly than the other two, though, so perhaps that will change in a few years.

Storage compartments can sometimes be too big on technical packs and too small on tactical packs.

Technical bags are often just a few large compartments, sometimes even just one large “bucket” compartment with no other pockets or features. They’re designed this way because the company assumes you won’t be going in and out of your bag quickly and frequently to pick and use one piece of gear — rather, they assume you’re carrying recreational gear on a trail and you’ll dump everything out all at once.

On the other hand, some EDC-oriented or tactical bags can get too crazy with micro pockets and overly-optimized organization. You might enjoy specialized individual pockets on your daily work commute for your sunglasses, pencil, pen, business cards, wallet, phone, and bicycle helmet, but that can be too limiting in a BOB.

We tend to dislike compartments that are too big because there’s no inherent organization, especially when you’ve been on foot and things jumble around or get squished.

Some packs have added a feature to minimize this problem: a removable, horizontal divider that creates a “shelf” somewhere in the main compartment, splitting the big compartment into two more manageable areas.

Technical packs often lack external pouches.

In addition to the same reasoning as the big main compartment, designers also try to keep the exterior smooth so there are fewer snag points in the wilderness. That might add a small stretch pocket for a water bottle, but even those aren’t good enough to hold a proper bottle in many cases.

We strongly prefer having at least a few external pockets for things you might frequently want to use without digging into the main pack, such as a canteen, compass, map, knife, multitool, flashlight, etc.

Technical packs are usually more comfortable and ergonomic.

Military grunts are told to “embrace the suck” while consumers looking at a weekend-warrior pack are more picky about comfort. Technical pack designers tend to be more thoughtful about comfort to meet that demand.

Higher-end technical packs will often have preformed hip belts, adjustable lumbars, adjustable spine heights, more cushion on the surface that rests on your back, extreme curves, and mesh webbing to create airflow gaps.

Tactical packs generally have better external attachment points.

You want the ability to attach gear to the outside of your pack. Yet bags intended for everyday carry and activities like day-trip hiking tend to have smooth exteriors. Sometimes it’s just for the sleek look, and sometimes it serves a purpose to reduce snag points when on a trail.

Even when a technical bag does have attachment points, because there’s such a wide range of recreational activities and specialized gear, you may end up with features that looked “attachey” at first glance in the store but were only meant for hanging an ice pick or something else not relevant to prepping.

On the other hand, tactical designers assume tactical people want to add stuff and you essentially only ever see two options: MOLLE or velcro.

Review: US Marine’s ILBE pack

“Gray man” and blending in with your environment

The punchline is easy: You want the ability to blend in with your surroundings when you’re in a situation that requires a go-bag. You don’t want a target on your back when people around you are panicking, nor do you want to draw suspicion from someone like a National Guardsman loading you onto an evac bus that you’re someone who’d have weapons in their bag.

What that means in practice is not so simple.

Consider that even just having a pack at all will in some cases be enough to make you stick out! It could even be the case that what makes you stick out like a sore thumb in one area is what helps you blend into another.

But, like all things, there’s a balance — and we think some people have taken the gray-man goal too far. We’ve seen people use a children’s school backpack (Hello Kitty!) or work briefcase, for example, which sacrifices too much functionality for the sake of blending in.

Think about what “average” means for the people around you.

If you live in lower Manhattan, the chances are higher that the people around you when SHTF will be carrying smaller day packs, professional work gear made of black/brown leather, and so on. A black bag with a sleek exterior will blend in better.

If you live in Bozeman, Montana, the people around you are more likely to be carrying an outdoor technical pack than a leather messenger bag. A green hunting pack may blend in better than a sleek black bag.

It’s easy to see that what even counts as “blending in” greatly depends on the people and norms around you — there is no universal answer.

Avoid camo and bright colors. Stick with solid, neutral earth tones.

Camo is a perfect example where there’s more risk than benefit. Even if you need to hide your bag, you can use materials found around the area, the tarp you’ll have in your bag anyway, etc.

Technical packs often come in bright colors. You may be in a situation where you want to be seen, but the backpack is not the right way to accomplish that.

You want external attachment points without glaring MOLLE/PALS fields.

MOLLE is an attachment system originally used in the military that has since spread into tactical consumer gear. PALS, sometimes used interchangeably with MOLLE, is the webbing weave that MOLLE gear attaches to.

Which is why most people will assume a bag with lots of conspicuous PALS webbing is more of a target than a plain bag. That’s caused some preppers to avoid any and all MOLLE.

We strongly recommend having the ability to attach stuff to the outside of your bag. You’ll likely want to carry your sleeping pad, bag, and/or tent on the outside of your pack. And you may want to add additional pouches, water holsters, and other modular accessories.

The problem is that some manufacturers — especially cheaper brands trying to make their junk seem cooler than it is — will slap as much MOLLE webbing around a pack as they have space for.

So when you’re shopping, be thoughtful about the amount and placement of the PALS fields. How many things do you expect to attach, and where? Is it overkill?

Prime spots for webbing are the bottom (to attach sleeping gear) and sides (for extra side pouches). It’s rare you’ll add something big to the main outward face of the pack, so only a few rows towards the top of that face will be fine for most people.

Some companies have started to include MOLLE attachment points that blend in better with the bag. The most popular version is “laser cut”, where the webbing is cut out of the core pack fabric rather than sewing extra material on top. Look for laser cut MOLLE that has some kind of reinforcement around the cuts so the attached gear doesn’t pull it apart over time.

Morale patches are another “tactical” signal.

Morale patches and other external decorations are common in the military and have spread into prepping circles. They’re fun, and we have plenty ourselves — my favorite is a Pickle Rick patch — but on a bug out backpack they’ll do more harm than good. Leave the “Death From Above” decal on your range bag.

Materials

Besides cost and how you generally get better materials the more you pay, the main spectrum in bag materials is between low weight and high durability. Go too light and your bag can tear from something like a passing tree branch. Go too durable and you’re carrying unnecessary weight.

Denier is a common fabric measurement. The higher the number, the thicker (and presumably more durable) the fabric strands. Silk is 1D while a human hair is 20D, for example.

Tactical packs tend to be in the 500-1000D range, reflecting thicker fibers that take more abuse, while technical packs are usually 210D, 420D, or a patchwork mix (eg. tougher strands on bottom, lighter strands on top) to cut down on weight. Technical designers assume it’s no big deal if you tear a bag on a camping trip, while tactical designers know a bag falling apart on a mission is a quick way to lose contracts.

Although you’ll be okay with anything in the 400-1000D range, current research suggests the sweet spot is around 500-600D. The market seems to be settling in this direction, to the point 1000D bags can come across as trying too hard.

More: Contributing expert Luke Fowler shares a deep Denier test he did on various bag fabrics.

Nylon is the best common material, and Cordura is a special form of nylon with high abrasion resistance.

Avoid polyester in bags over $100 (it’s unavoidable in many cheaper bags) — even if it’s labeled “tactical” or “ballistic” polyester, which is usually a nonsensical marketing label used by cheap brands.

Just like the tarp you’ll carry in your go-bag, a transparent polyurethane (PU) coating is applied at the factory. But the coating is more for seam integrity than for waterproofing — any coating will wear down from water exposure over time.

Cheap coatings will get cloudy, crack, or peel. Pay extra attention to this when buying used.

Other bag features

Common features you should avoid:

- Laptop sleeves are generally a waste of space because you won’t have a laptop or anything of similar size/shape that justifies its own compartment.

- Hydration reservoirs are a similar story — you shouldn’t use a bladder in your go-bag anyway, and there’s nothing else worth having that dedicated pocket for (although it’s usually less wasteful than a laptop sleeve).

- Built-in raincovers aren’t horrible, and it’s fine if you find a great bag with one that isn’t too intrusive. But they’re often too bulky and waste space. You will have a tarp and other rain cover gear if needed.

Buy front-loading bags (or hybrids), not just top-loaders.

One of the most common problems with technical backpacks is the top-loading design, which means the only access hole to the main compartment is at the top of the bag (often hidden under the lid, as in the following picture), looking down to the floor.

Do not buy a technical-style pack without knowing how you get into the compartments. As of this writing, for example, REI’s website has only two out of 72 total bags that can load from the front, and only one out of 72 is even close enough to be a candidate.

That’s fine for hiking and does reduce water penetration (since the entry points are usually hidden), but it sucks in an emergency — you want to be able to access the specific gear you need without having to dig through or dump out everything.

Thoughtful attachment points for shelter/sleeping gear.

Unless you’re carrying a minimalist bag, you’ll probably want to carry a few items on the outside, namely some or all of your sleeping pad, sleeping bag, and tent. They take up too much room on the inside of the pack and there’s no harm in carrying them outside.

We strongly favor packs where the designer considered this and built thoughtful attachments, straps, or other ways to carry that gear in proper spots.

For example, we like when there are built in straps near the bottom but not on the bottom. When the only place you can strap a tent or sleeping bag is underneath the pack, you can’t easily set the pack down on the ground. Straps that hold the gear just off ground level make this easy, and the extra gear even helps stabilize the bag while standing upright on its own.

Removable sub-packs that can also serve double duty.

Technical packs sometimes feature a removable top “lid”, the compartment that sits over top of the bag’s main compartment access. Some models even include an extra strap or two so you can turn the separate lid into a smaller day pack or shoulder sling.

These types of areas are also nice because it’s another space where you can lay bulky external items like rope, sleeping pads, sleeping bags, or rain jackets and then cinch them down between the top lid and main body, holding them flat on top of the bag instead of strapped to a side.

High-visibility interior colors help you find what you’re looking for.

Unlike the exterior, we like bright colors on the inside of pockets because it helps create contrast against your gear. Imagine digging through a solid black bag’s main compartment, at night, looking for your all-black flashlight.