Discussions and debates about the COVID-19 pandemic almost always hinge on the flood of numbers about tests, cases, recoveries and deaths in locations around the world over time: what they are, what they mean, and how reliable they are. We’ve covered a lot of different aspects of these questions, but one that arises constantly is whether Chinese COVID-19 statistics can be trusted.

“You can’t trust the Chinese statistics” is the center square on coronavirus discussion bingo. But the answer to “can we trust Chinese COVID-19 statistics?” depends on what is meant by the question.

It’s true that the Chinese government has a deserved reputation for dishonesty and is known to have lied about COVID-19 in the past, and therefore, specific individual numbers from China cannot be relied on to be numerically correct. However, the basic picture painted by Chinese COVID-19 data as a whole is directionally and qualitatively correct, and is constantly being confirmed independently.

In addition, the question is not as consequential as many people think. Every major piece of information we know about COVID-19 can now be supported without using any statistics from China.

You can’t trust Chinese government’s specific numbers

The Chinese government has lied about COVID-19 a lot, especially in the early days. We reported on these lies.

This attempts at a coverup appear to have mostly stopped in February, when WHO teams were finally allowed into Hubei province and information sharing ticked up dramatically. And certain streams of information like the peer reviewed scientific literature appear to have largely maintained their integrity throughout. However, there’s no doubt that Beijing has lied about COVID-19 in the past and could be doing so again.

So, if the question is whether we can actually be sure that Shanghai currently has 141 active cases and has had 6 deaths, the answer is no. It could be 300 cases, or 500, and it could have been 20 deaths, not 6. And certain claims, like the notion that China attained a near-zero rate of hospital-transmitted infections at the tail end of the Hubei outbreak despite allowing over three thousand doctors and nurses to become infected in February, are probably wrong.

You can trust the big picture: China contained its outbreak

But when people say “we can’t trust Chinese numbers,” what they very often mean is that the inflection in growth of the epidemic in China over six weeks ago was a lie and that it has continued to grow unchecked since then. We have other ways of evaluating that claim, and they show that this claim is wrong.

China isn’t a complete black box. The Prepared corresponds with primary sources in Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen, and Wuhan who tell us what’s happening there. There are also lots of foreign reporters who, while they face some censorship, would still get word out of an uncontrolled outbreak.

What happened in Wuhan while the epidemic was overwhelming hospitals is something no one could miss: people were banned from traveling or leaving their homes, the military was delivering food to houses, bodies were lying in the streets for hours before being collected, sick people were jumping off bridges to avoid going home and infecting their families, and every medical clinic was jammed while emergency clinics were set up in tents in parks. At night the empty city was suffused with a mixture of ambulance sirens and howls of distress from trapped residents on their balconies. The dead weren’t getting funerals, just cremation notices, and the crematoria were running around the clock.

It’s the same grisly scene now unfolding in Italy, Spain, Iran, and New York, and even many of the details are the same.

And during all this time, sources from China, including western media there, independent Chinese media, Chinese doctors and scientists, and our primary sources in China were telling us about it.

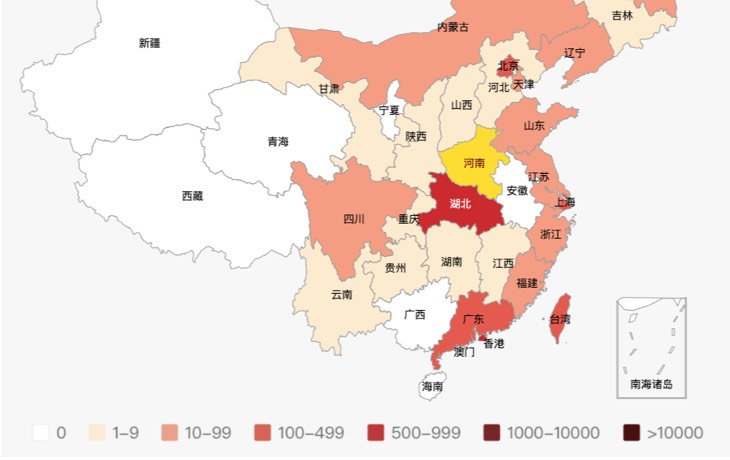

Based on the numbers from other Chinese cities that already had hundreds to thousands of officially acknowledged confirmed cases in the middle of February when the reversal happened, if there hadn’t been a reversal, every city in China would be in the same boat as Wuhan at its peak by now. But they aren’t. We can’t tell whether the statistics are correct at a granular level, but we can tell that.

Instead what we see is directionally and qualitatively what the statistics show: China is opening back up, and so far case numbers are not exploding. The fact that the USA is right now embroiled in a controversy over whether to allow importation and use of (relatively) abundant Chinese face masks tells the story by itself.

Chinese government statistics don’t matter that much right now

The Prepared made an editorial decision in February to stop reporting any important factual analyses about COVID-19 that could only be supported with granular statistics from China, because of ongoing accuracy concerns. That decision has wound up not mattering much, because as the epidemic has grown outside of China, every important property of the virus and society’s reaction to it has become verifiable without Chinese data.

From CFRs, R0, the effect of different social measures on R, clinical trials on major possible drugs and vaccines, what a city looks like at different levels of local COVID-19 spread, to what it feels like to be stuck at home for long periods, every piece of the picture has become visible outside China.

And the answers we’ve been getting have mostly matched what we got from China. Amazed that China managed to contain SARS-CoV-2? Korea did the same. Amazed that they built hospitals so quickly? It’s happening in the USA too. Don’t believe their CFR numbers? They match the ones from other countries.

Fundamentally, there hasn’t been much directional or qualitative information out of China that was hugely implausible since the early days of the Wuhan outbreak.

So, when you’re thinking about whether to trust numbers or reports from China, ask yourself:

- Is this a granular piece of specific information or a directional/qualitative piece?

- Does it come from the Chinese government, or an independent source, or a primary source, or academics?

- If it were wrong, would sources in China be able to expose that?

- Does it fit with what we’re seeing in other countries?

The world is full of information, much of it bad. But basic information literacy practices don’t stop working at the water’s edge, and unlike in logic puzzles, there is no country whose leaders only tell lies.