Editor’s note: In yet another example of Covid disruptions, many people are struggling to find the seeds they want for the 2021 season. Check out the tips below if you just can’t find store-bought options.

Seeds are an obvious part of your personal survival garden, which might be part of your food prepping alongside normal stuff from the supermarket and freeze-dried food kits or staple ingredients.

Early spring is the rush season. Seed companies tend to send out their catalogs over the winter, while their customers are stuck inside dreaming about planting as soon as the weather breaks.

Since almost all seeds last for at least a few months — the average shelf life is a few years with reasonable storage — you can avoid the rush by buying either before or after everyone else does. The safest window to buy is early winter to avoid the rush while minimizing how many months you’re holding onto the seeds before planting.

Another good time to buy seeds is the summer. By then, most gardeners have the seeds they need, or are busy tending their gardens, and aren’t racing to buy seed. If you store your seeds properly, they should be good to go for the next season.

Summary:

- Seeds don’t last forever. If you want them to be viable after a year or so, be sure to store them in a cold, dry, and dark place, ideally air tight.

- “Heirloom” seeds are usually preferred over “hybrid” seeds because they do a better job of predictably creating new generations of seeds for you to plant. That self-sustainability can be really useful in a long-term emergency where you can’t depend on other vendors.

- GMO seeds aren’t really a thing in personal gardens, moreso just commercial farms.

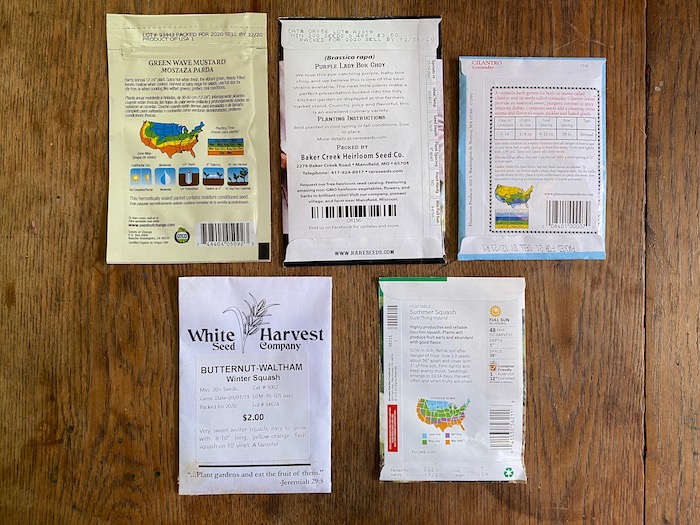

- Seed packets usually have all the core info you need, such as recommended sunlight levels and how far apart to plant the seeds.

- Many types of food you’ll grow, such as potatoes and sweet potatoes, don’t come from seeds. They come from roots/tubules that branch out from the parent plant.

- It’s worth buying seeds from reputable vendors so you know you’re actually planting what you wanted to and it’s a quality product. There’s a lot of junk out there.

- Local gardeners are a great source of quality seeds. Make friends!

- You can improvise by using seeds/starters you already have around your home or can find in a pinch, such as tomatoes, peppers, potatoes, and even sunflower seeds.

- Seeds are cheap! Don’t be afraid to buy whatever looks interesting or fun to plant. That’s part of the fun of gardening.

Be prepared. Don’t be a victim.

Want more great content and giveaways? Sign up for The Prepared’s free newsletter and get the best prepping content straight to your inbox. 1-2 emails a month, 0% spam.

Where to buy seeds online

The internet is usually the best place to buy open-pollinated seeds. But it’s important to buy from a reputable source so that you know what you’re putting in the ground is actually what you ordered, it’s not a lousy seed, it’s not a mislabeled invasive plant that becomes a nightmare to remove, etc.

These are well-reviewed online sources for heirloom seeds:

- Annie’s Heirloom Seeds

- Azure Standard

- Baker Creek

- Clear Creek Seeds

- Fedco Seeds

- Hoss Tools

- Johnny’s Selected Seeds

- Peaceful Valley

- Renee’s Garden

- Seed Savers Exchange

- Southern Exposure Seed Exchange

- Tator Man

- Territorial Seed Company

- White Harvest Seed Company

Baker Creek is probably the most popular, though it’s also the first to be sold out when panic buying takes hold.

Sometimes these companies offer seed collections where you can buy a wide variety of seeds, usually at a discount. When these are offered by reputable companies, they’re usually a good buy if you want a jump start on your seed collection. They often include extra goodies like handbooks or planting calendars. Just closely read the contents list to make sure you would want to plant most of the seeds. Also note that this can be a way for seed companies to get rid of older seed packets, so you’ll want to put them near the front of your planting queue.

However, some preparedness companies also sell seed collections. These seeds are often old when you get them and haven’t been stored as carefully as a dedicated seed company would store them. It’s best to stick with the experts.

Finding offline / local seeds

Finding seeds isn’t hard. They’re sold pretty much everywhere: drug stores, gardening centers, hardware stores, Walmart, Tractor Supply, ad infinitum. However, you won’t find the variety and quality that the premium online retailers offer. But they’re usually fine.

And if you want to buy pre-sprouted annual plants to transplant into your garden, buying local is pretty much your only option.

Another avenue for buying seed is from other gardeners. Finding them will take some legwork since it’s a local and personal connection. If you don’t know where to start, your local farmer’s market is a good place to ask around. For example, Amish and Mennonite communities often sell tomato and pepper plants alongside fresh produce.

Many public libraries have a seed exchange program, like the Nashville Public Library. You check out seeds just like books, and when the season is over, you save seeds from your crops and “return” them to your library.

Basic seed terms

Germination simply means a plant successfully emerging from a seed. Not every seed you plant will grow, so the germination rate is the percentage of seeds in a batch that germinate successfully.

Variety and cultivar refer to how the plant came to be. In the simplest terms, a variety is a type of plant that occurs naturally while a cultivar is a plant specifically bred by humans. There is some disagreement over the exact definitions, and many people use the two interchangeably — but ultimately, it doesn’t matter to you. If someone says variety or cultivar, they mean a type of plant, like Purple Lady bok choy or Cherry Belle radish.

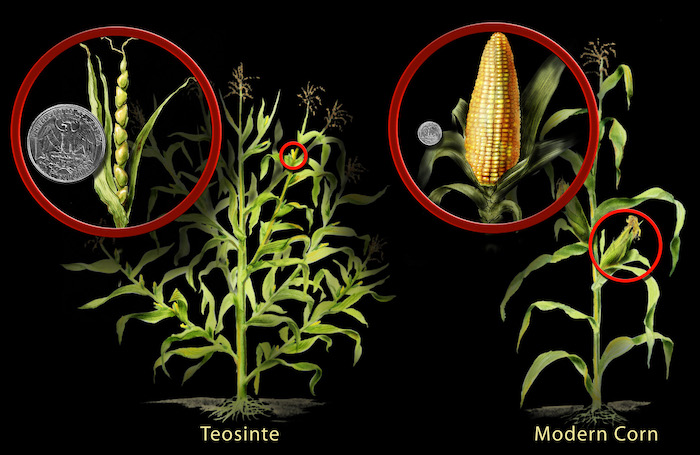

However, some try to equate cultivars with hybrid plants and insist that heirloom cultivars are entirely natural. But that just isn’t true. Many common fruits and vegetables have been bred by humans over thousands of years to maximize desirable traits. Wild carrots, bananas, and corn are very different from what you grow in a garden. Likewise, wild garlic bears little resemblance to the garlic you’re used to.

There are three types of seeds (broadly speaking). An heirloom seed just means that it’s an old variety, at least 50 to 100 years old, though the definition is fuzzy. Most heirloom seeds are open-pollinated, which means that the seeds the plants produce will reliably produce more plants of the same characteristics. Heirlooms come in a dizzying array of varieties, some of them quite funky.

Hybrid seeds create the food you usually find in big box stores because they’ve been bred for specific characteristics like size, color, or disease resistance. It’s similar to how dog breeders might mix different breeds to accomplish a certain personality trait. They are often confused with GMOs, but hybrids are not GMOs because they’re not modified in a lab — just intentionally bred. Hybrid plants may grow more reliably for you, but the subsequent seeds may not produce food at all, or they may produce something quite different than the first generation you planted.

GMO seeds are modified in a lab to offer specific characteristics. GMOs are controversial because many believe them to be unhealthful and unnatural — although scientific evidence so far has shown that GMOs are safe to consume. Safe or not, GMO seeds are often made and sold at high profit by companies like Monsanto, who then abuse the legal system to protect their ‘proprietary’ seed. Many GMO seeds are also designed to tolerate herbicides well, leading to their increased use, which is linked to all sorts of bad things like bee die-offs and fertility problems. But in reality, you as a gardener probably don’t have to worry about GMOs since they are largely sold to commercial farmers.

Some seeds are marketed as “organic,” and can even be certified as such by the USDA. All this means is that the plants that the seeds came from were grown on a certified organic farm. Ultimately, whether a seed is “organic” or not is utterly meaningless. What makes produce organic is the lack of use of chemical pesticides, herbicides, and fertilizers.

Choosing between heirloom vs. hybrid seeds

Humans have been cross-breeding plants for thousands of years, so the line between heirlooms and hybrids gets kind of fuzzy.

The general recommendation is that heirloom seeds are better for preppers because they make predictable offspring over generations, creating a sustainable supply. You buy seeds, plant, harvest the new seeds created by what you’ve grown, replant those new seeds, and the cycle repeats itself. Hybrid seeds are more likely to fizzle out over the generations, to the point food won’t grow at all, or if it does, it doesn’t have the characteristics you first chose.

Simple analogy: When dog breeders want to make a puggle (a “designer hybrid”) they tend to mix a pug and a beagle. But there are plenty of puggles around these days, so why don’t they just mate puggles to get more puggles? In practice, things turn out better when you recreate the “hybrid” crossbreed from scratch instead of letting the hybrids self-replicate over the generations.

You would choose to buy hybrids when you need certain characteristics to overcome a problem. For example, County Fair hybrid cucumbers are highly resistant to disease and many people report being able to grow those after failing with other types of cucumbers.

That said, if you already have — or can only get — hybrid seeds, don’t worry too much about it.

Seeds vs. seedlings

If you visit nurseries or garden centers during gardening season, you’ll see a large variety of seedlings for sale — seeds that have germinated and just started poking through the surface.

Seedlings are much more expensive than seeds, but there are times when it makes sense to buy seedlings instead.

Tomatoes, peppers, and brassicas like broccoli and cabbage are typically transplanted into a garden instead of being sown directly. In the case of tomatoes and peppers, the growing season usually isn’t long enough in the United States to get a good harvest unless you start them indoors while the weather is still cold.

Likewise with brassicas, they enjoy cool spring and fall weather but dislike hot summers and cold winters, so starting them indoors helps you get a productive crop. Also, the seeds of many cool-weather crops won’t germinate well in cool weather. For instance, lettuce germinates best at 70 to 75°F but grows best at 60 to 65°F.

You can start these plants indoors yourself, but it’s a skill that can take time to learn. Young seedlings need a sterile environment, a lot of light, and just enough water. They’re also prone to disease. It’s a skill very much worth learning, because it’ll make you more self-sufficient and save you a lot of money, but buying seedlings to transplant is a good idea for beginners because it reduces guesswork and builds confidence.

Seedlings are good for beginners because seeds can sometimes be tricky to germinate outdoors. Maybe the weather is a bit too cool, you planted too deep, or a pest ate the seeds. If you have trouble even getting started because your seeds don’t sprout, try buying some seedlings to get a jump start.

Another reason to buy seedlings is if you’re in a rush. You forgot to start seeds on time or maybe your seedlings died. In those instances, a trip to the nursery can save your gardening season.

When purchasing seedlings, opt for nurseries over big box stores because the employees are more knowledgeable (they might have even grown the seedlings themselves).

When choosing seedlings, choose healthy-looking plants without wilting or blemishes.

However, if you can start a plant from seed, it’s usually the best way to go. It’s less expensive and seeds store well, unlike seedlings that need to be planted as soon as possible. However, some plants are difficult to grow from seed even for experienced gardeners.

Potatoes can grow from seed, called “true seed,” but gardeners almost always grow them from other potatoes. You can grow potatoes from store-bought potatoes, but to prevent disease it’s recommended to buy special “seed potatoes.”

Sweet potatoes can grow from true seed, but are usually grown from slips, or little vines that grow from other sweet potatoes. You can buy the slips by themselves, or you can grow your own.

Onions and garlic can be grown from seed, but it takes a long time and those seeds have low germination rates. Most gardeners buy small bulbs of tiny onions to plant instead, called “onion sets.” Garlic cloves can be planted directly and are sold as “garlic sets.”

Trees and berry bushes are usually started from cuttings instead of seed, but again, that’s a skill you can develop with time. The next time you eat a peach, save the pit, and follow David the Good’s advice on sprouting it. You might end up with a free peach tree!

Seed packets should tell you most of what you need to know

It’s helpful to read seed packets before you buy, and especially before you plant. Designs vary by vendors, but look for these important parts:

Dates: The packet should have some indicator of when it was packed. It might say “packed for year” or give a sell-by date. Seeds don’t last forever, so you want ones packed in the current year for maximum freshness. Some packets will have a germination date, when is the last time the company tested that cultivar seed to ensure good germination rates.

Lot number: Many seed packets have a lot number. If you complain about a seed to the company (eg. it has a poor germination rate) they will likely want this number so they know which batch to keep an eye on.

Days to germinate: How many days does it take between planting a seed and a seedling emerging? The packet should say. When you plant a seed, it’s worth doing a little date math and marking the expected germination dates on your calendar so you know whether to replant or not.

Depth: This says how deep to plant the seed. A good rule of thumb is to plant no deeper than the diameter of the seed.

Plant spacing: This tells you how far apart to plant the seeds, and may also recommend how far apart to place your rows. For example, squash seeds will recommend 3-4 feet between plants. Many seed packets also recommend over planting and then thinning to the final desired spacing.

If you do biointensive gardening or Square Foot gardening, those systems usually offer their own suggestions and skip the thinning step, so you just plant at the final spacing. If in doubt, go with what the packet says.

Climate: This can be presented in various ways, sometimes as a map of climate zones or it may just list ideal germination temperatures. This helps you know if the seed is practical to grow in your area. Learn more about climate zones.

Sun: Most seed packets also list how many hours of sunlight plants need a day, so you know whether to plant them in a sunny or shady area.

Pelleted seeds

Many seeds are tiny, such as lettuce and carrot. It’s difficult picking out individual seeds to plant, and especially hard for machines to do so, so many seed vendors encase individual seeds in clay pellets. These are called pelleted seeds.

Pelleted seeds might help if you have trouble planting these types of crops. But there’s a big downside: Pelleted seeds are usually presoaked in water to help their germination rate, which results in a much shorter shelf-life than regular seeds. So they’re good for immediate use, not for storage.

Johnny’s Selected Seeds sells pelleted heirloom seed, and they offer this warning: “Pelleting offers many advantages, but the pelleting process also shortens the shelf life of the seed. We recommend using pelleted seed within one year of purchase.”

Finding free seeds

Can’t buy seeds from a store or find a local friend? You probably already have some seeds around your house! Some ideas:

- Birdseed can contain numerous useful things to plant, like corn, sunflower seeds, and sorghum.

- Dry beans like pintos, lentils, and chickpeas can be directly planted.

- Garlic cloves can be broken off and planted.

- Peppers and tomatoes: You can cut these down to just the area where the seeds are naturally attached, then plant the remaining shell with the seeds attached. The remains of the food decompose and fertilize the seeds.

- Whole uncooked popcorn kernels can be planted to grow seed corn that can be ground into flour.

- Potatoes can be replanted. Planting store-bought potatoes isn’t ideal, but they’ll grow just fine. Leave the potatoes exposed to the sun until they begin growing “eyes,” a process called chitting, and then plant them. You can expand your supply of potato “seeds” by slicing budded seed potatoes so that each piece has 2-3 eyes, and then letting the cut ends harden into a leathery skin before planting.

- Spices can be planted if you have a whole / uncut form of the spice. For example, coriander grows into cilantro. Whole cumin is another spice you can plant.

- Sweet potatoes can be grown in two ways. Either bury sweet potatoes in a shallow pan of soil and leave it in the sun, or put toothpicks in a small sweet potato, suspend half of the sweet potato in water, and put the seed potato in a warm and well-lit place. You later cut off the slips and insert them directly into well-drained soil (if your soil isn’t well drained, you can hill it up and plant in the hills).

How to store seeds

Seeds do not last forever. Some are only viable for a few months, while others can be planted for years. There are a few things you can do to extend their lifespan:

- Keep them cool. Don’t store seeds in an outdoor shed. The best place for seeds is a refrigerator, freezer, or a root cellar if you have one.

- Keep them dry. Wet seeds will mold or rot.

- Seal them in airtight containers. Ideally glass mason jars, but Ziploc bags work too.

Just as you do with food, practice the first in first out method. Buy fresh seeds every year and plant your oldest ones first.

Unsure if your old seeds are still good? Plant a few in a pot or a seed tray and see if they germinate. If you have some fresh seeds of the same type of plant around, plant those in parallel so you can compare the results.

Beyond lifespan, once you build up a large enough collection of seeds you’ll want some way to organize them. Cardboard beverage or jar boxes with dividers are useful and inexpensive. Many gardeners have started using plastic photo cases, which have a briefcase-style case fitted with 16 smaller cases sized just right for seed packets. You can use each photo case for a different type of seed: greens, tomatoes, squashes, brassicas, etc.