Book Review: “Walkable City Rules”, by Jeff Speck

[The walkable city of Söderköping, Sweden. By WrathOfGnon]

If you’re a prepper in a city, can you make your city itself more resilient and prepared?

The classic prepper goal is to become an independent homesteader – find your own piece of land, and raise your own food and resources.

But what about those who can’t, or won’t?

Can you live in a city and still be an effective long-term prepper? Can you improve the preparedness and resilience of the neighborhood and community around you?

I wanted to research the opposite end of the spectrum and analyze city living from the perspective of emergency preparedness. What useful actions could you take as an individual or a community?

Jeff Speck delivers some answers in his book “Walkable City Rules”. Speck outlines one hundred and one steps cities can make to become more “walkable”, which he equates with being more habitable, resilient, vibrant, and well off. Not everything in Speck’s book is directly applicable to prepping. But I wanted to see how many useful actions I could find.

What is a Walkable City?

Walkability is “an indicator of urban vitality”. Speck argues that the more walkable (and rollable) cities are, the more people they attract, the more jobs they create, and the better livelihoods they can support. Walkability makes cities more livable and successful.

To succeed, walking around a city must be:

- Useful. Most aspects of daily life are nearby, and organized enough to get to.

- Safe. Not just being safe, but feeling safe for pedestrians, which can be harder.

- Comfortable. Buildings and landscapes shape the streets into “outdoor living rooms” – cozy places that are welcoming. Not just a wide open space.

- Interesting. Lined with unique buildings, friendly faces, and the signs of human life.

Speck has details on the best neighbourhood structure – compact, diverse building types, with well-defined and engaging “edges” between private and public spaces. They contain a wide variety of activities in close proximity. “Good cities are designed and organized in compact neighbourhoods linked together.”

Walkable also means “Rollable”

Speck’s definition of “walkable” also means “rollable” – a city that is good for bicycles, wheelchairs, roller blades, strollers, or whatever wheeled method you use to get around. People who are rolling will be able to access and enjoy the same areas as people who chose to walk – and gain all the same benefits of an improved, interesting space.

Two Books: Read the Second One

Spec has written two books: “Walkable Cities” (in 2012) and “Walkable City Rules” (in 2018). Read the second one – “Walkable City Rules”. It’s updated, clear, and more actionable. It has impactful before/after pictures and diagrams, and includes more detail on fundamental concepts – such as the idea that good urban design focuses on dispersion: where trips are distributed among a large number of parallel streets, so that no street becomes overwhelmed. This means every street receives benefits from people passing through – improved safety from many eyes on the street, more traffic for merchants, etc. As well as discussion on how improving car traffic flow directly hurts all other aspects of a city you might want to improve: density, diversity, walkability, property value, resource consumption, life expectancy, educational attainment, patent creation, GDP, carbon footprint.

Benefits of a walkable city

Speck outlines five areas of benefit: Wealth, Health, Climate, Equity, Community.

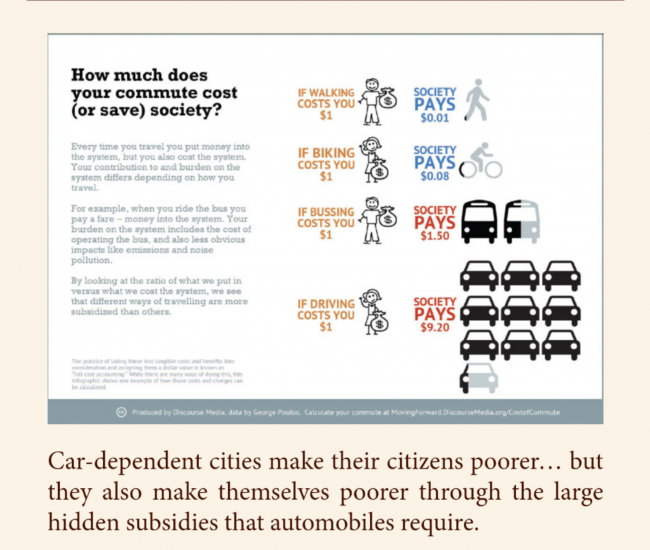

1. Wealth. Walkable cities have higher property values, attract talented people to live there, and create more jobs. One estimate translated each Walk Score point (on a scale of 100) adding $2,000 to a home’s value. Since the average American spends 20% of their income on transportation, more walkable spaces can save you money, which is then often spent locally. Speck also discusses the (apparently large) hidden costs of subsidizing roads and cars: “The cost of all parking spaces in the US exceeds the cost of all cars, and may even exceed the cost of all roads”. “America sends $600,000 overseas every minute in support of our current automotive lifestyle”.

2. Health. The more that people walk or provide their own transportation, the more physical exercise they get. This directly translates to healthier communities and citizens. It also lowers healthcare costs for cities – one Iowa study estimated that investing in biking infrastructure could save the state $87 million in health care costs. Walkable cities have fewer car crashes and cleaner, less polluted air.

3. Climate. Speck believes we should measure carbon emissions per person, not per area or square mile. “Places should be judged not by how much carbon they emit, but by how much carbon they *cause us* to emit”. The more walkable we make cities, the less driving is required and the less we pollute. “How we move determines how we live”.

4. Equity. Speck reviews studies that show how cities with more transit choice demonstrate less income inequality and less overspending on rent. They help to give children more independence and extend mobility for the elderly.

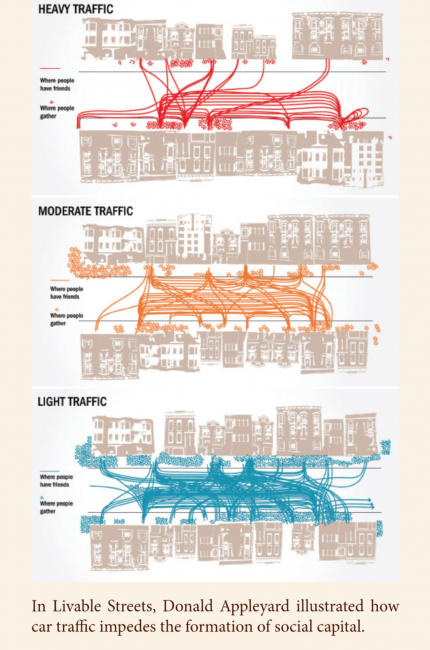

5. Community. In walkable spaces it is difficult to spend much time sneaking around without being approached by an inquisitive resident. Where people walk, communities are more self-supervised and have lower crime – two studies calculated that walkable areas are 19% safer for both car crashes and crime. People have more interactions with their neighbours, more opportunities to get to know each other, and more chances to form positive bonds. Walkable communities can build more social capital and gain more civic involvement. People have more time for clubs, volunteering, and community projects when they are not stuck commuting in a car.

In Summary: A city with more cash to build infrastructure, a healthier population (so less drain on the healthcare system), and more connected neighbours that know each other and are more likely to help each other? Sounds like a more prepared city to me.

Where Can You Not Do It?

Speck agrees that this won’t be feasible everywhere: “Most Americans live not in big cities with big public transit systems, but in smaller places that face a dramatically different landscape [around] public transportation”. He focuses on “What changes can be made, in the least time, and for the least cost, that will have the largest measurable impact on the amount of walking and biking?”.

Transit needs to be a convenience, not a rescue vehicle. Focus on opportunities where it can offer a better experience than driving.

Core Concept: Induced Demand

Induced Demand means: Adding more roads makes people drive more. This is a core concept of the book. Speck argues: do not try to “fix” traffic congestion by adding more roads – this only creates more congestion (and pollution). Instead: provide better options.

So what can you do about it?

The book has so much information, but how much of it is useful to prepping? I estimate – perhaps 30%. The book is extremely useful if you are a city mayor, or a town planner with an approved budget for construction. It may also be useful as a *defense* against making your city worse – once you know the concepts in Speck’s book, you can argue against harmful changes with evidence. If you are civically minded or want to engage with your city officials, the book could also be very helpful.

Below I attempt to collect and synthesize several ‘tiers’ of actions and improvements that regular people could make to improve resilience and preparedness for themselves and their community.

Most Impactful Action: Plant More Trees“There is no better use of public funds.”

Speck argues the biggest thing any city can do to improve resilience, walkability, and community is to plant more street trees. Usually: plant these in all medians and boulevards – the space between the sidewalk and the curb.

Trees help in many ways to:

- Provide shade

- Reduce ambient temperatures – sometimes by 10 degrees or more. The US federal

- government reports that a single mature tree has the same cooling impact as “ten room-size air conditioners operating 24 hours per day”.

- Absorb excess rainwater, reducing or preventing flooding

- Absorb car exhaust emissions. Because street trees are so close to the source of cars and tailpipes, they can absorb 10x the amount of carbon dioxide as trees farther away or outside of a city.

- Provide UV protection

- Limit the effects of wind

- Slow down cars, which protects neighbourhoods and people walking and playing

- Reduce crashes

- Shape the space and improve the sense of enclosure (makes people more comfortable)

- Improve health. Several studies have shown that regular exposure to trees prolongs life, aids mental health, reduces asthma, obesity, stress, and heart disease, and makes people happier. Humans enjoy and benefit from being around trees

- Improve property values. One study showed that street trees in a neighbourhood improved property values by 9%. Cities that invest in street trees may gain back $12 in tax revenue for each $1 spent.

- Improve retail viability. Shoppes on streets with good tree cover may earn up to 12% more revenue.

Spec has details on selecting the correct types of trees (hardy local species; same type through a whole neighbourhood), how to space them, and how to build the correct soil mixture below the sidewalk.

Speck’s second most effective improvement is to correctly add street parking. He argues that it creates a “barrier of steel” between people driving and people walking, which makes pedestrians safer and encourages business at shoppes and restaurants. However, implementing parking may be more in the realm of city planners and officials.

Level One: Actions By Yourself

Prepping actions you can take by yourself, in the city, include the standard set of prepper activities: plant trees for food, shelter, and shade; grow a garden; collect and use rain water; and improve your home to be more passive and resilient.

Beyond that: go for walks around your community and learn your local area. What green areas, playgrounds, and parks do you have? What types of useful or edible plants grow nearby? Do you have sources of water? Perhaps you can mark all of these on a map.

As you travel you could find and rate the useful and interesting locations and streets in your community. Perhaps you can identify green/yellow/red zones that are the most walkable, or could be easily improved to attract more use and more people. Walking around may help you meet your neighbours.

Speck suggests: Houses with front porches, stoops, bay windows, or front-facing hangout spaces create a more friendly community zone and help neighbours interact. Perhaps you can buy or build a house with a porch, or put a bench, bird feeder, or interesting plants and features in your front yard.

Speck suggests using ‘friendly’ lighting – a warm continuous spectrum light, like an incandescent. “Safety comes not from brightness, but from population”, when more people decide to walk in an inviting area.

Level Two: Actions In Your Community

Perhaps you could agree on a tree to plant in a shared area with your neighbour. Walk around your neighbourhood and talk to your neighbours as you meet them. Join or start a community gardening club. Or host a block party. This may be a good way to meet your neighbours and do good in your community. Participate and help to plan local features – parks, playgrounds, etc.

Work to get lowered speed signs in your neighbourhood, to encourage more walking and make it safer. Speeding risks, damage, and deaths rise exponentially, so you want cars driving around 20 mph / 30 kph in neighbourhoods. By his own admission – half of the points in Speck’s book (!!) focus on actions that work to reduce driving speeds and create safe areas for walkers. You can also survey which streets have four lanes and advocate for them to become three-laners with a turning lane and a treed median or parking. These are safer, more useful and walkable, and still serve the same number of cars. Turning multi-lane one way streets into two-way streets offers the same improvement.

Speck encourages the building of “granny flats” – a small, livable space in the same lot, often as a building in the backyard above the garage or as part of the garage. These can be rented out to members of the family to provide income – e.g. to grandparents, or to a child going to college or university. Or they can be moved into while the main house is rented. This “introduces affordable spaces in a dispersed way throughout the city”. It increases neighbourhood density, putting more feet on sidewalks and making transit service and local shopping more viable. The spaces are usually closely monitored to prevent abuse, as the landlord literally lives right close by. You could get involved with your community or city to make sure this type of housing is supported.

Level Three: Actions In Your City

Plant more trees. See if your city has a volunteer tree planting program. If you are more civically minded: get involved in some community planning. Check if your city has ever performed a walkability study, or start one to show how it is done. Encourage the creation of public art that helps to liven up shared spaces. Check if your city has grants or a Mural Arts Program to support this. In the three+ decades that Speck has been learning about walkability, he has honed in many of the phrases and wording that are most successful for change – e.g. “reducing illegal speeding” and “creating a barrier of steel”.

What Is It Lacking

I wish the book had a clear, direct guide on how to perform a Walkability Assessment, including all of the steps, how to score streets and buildings, and how to assess the anchors and “walkability network” of your neighbourhood. This would go a long way toward figuring out which actions could or should be taken, and which items you might be able to do yourself.

As is, Speck provides four sample assessments he did in actual cities in the United States. The links have all died, but I found and collected three of them using archive.org – links at the bottom.

Many of the improvements also feel like they require a high level of civic engagement and interaction, which may be lower on most prepper’s activity lists than the standard, individual steps you can take.

Summary

“Walkable City Rules” is light, easy read. It has many great suggestions for improving a city. All mayors and city planners should read it. From a prepping perspective, it has several good suggestions you can take on your own, and many resources if you want to become more civically engaged. If you do not want to be civically engaged, it may not be that useful.

I learned a lot. I do not feel it answered all of my questions about the potential success of prepping inside of a city. I will keep looking. Perhaps as the idea of “walkability” becomes more popular, cities around the world will just happen to become more prepared and resilient.

Inspiration

For a great mix of beautiful, inspiring images and discussion on how to make cities better – I recommend the twitter feed WrathofGnon . He discusses what makes “good urbanism”. I originally found this book from his recommended reading list. He also has a substack blog with more detailed writing.

Further Resources

- WalkScore.com – check your city

- Sample Walkability studies (PDF) – Tulsa Oklahoma, Lancaster Pennsylvania, Albuquerque New Mexico (web page). To see how the process is done.

- Wikipedia – Mural Arts Program

- “Tactical Urbanists’ Guide to Getting It Done” (has link to downloadable PDF). For those interested in improving their city or learning about other options.

- Tactical Urbanism v2 (not downloadable)

(edit: note that Söderköping is in Sweden, add link to homestead review)

-

Comments (12)

-