A 2003 European heatwave killed around 50,000 people and caused €13B in damage. And those parts of the world that historically didn’t install air conditioning, such as Northern Europe and the US Pacific Northwest, are getting warmer — the number of severe heat waves in those areas is expected to double in the next few decades due to the climate crisis.

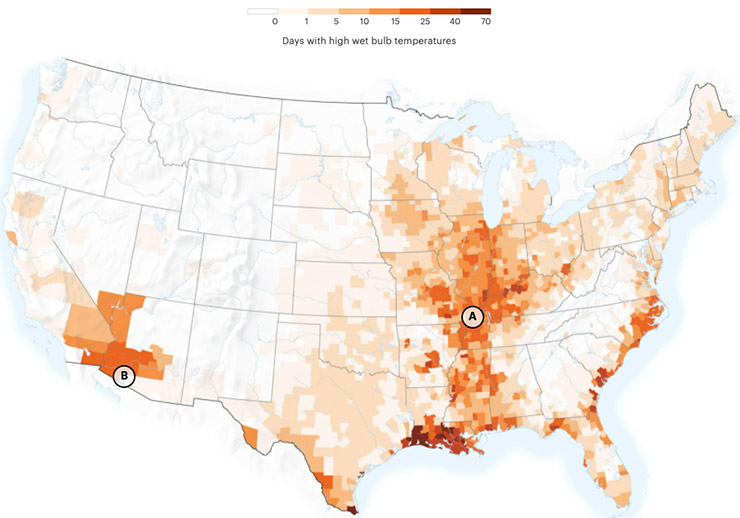

Official projections show that many populated areas of the world will become “uninhabitable for humans” for at least part of the year. As global temperatures rise, so does the “wet bulb” temperature, which is a function of both heat and humidity. As the humidity rises, your body is less effective at cooling itself off through sweat.

At 95°F (35°C), the human body can no longer cool itself and people die. Consider Phoenix, Arizona, for example, where it’s projected that more than half of the year will be over 95°F and changing weather will turn their traditionally dry heat into a more humid environment at risk of dangerous wet-bulb temps.

Even if you do have AC, many modern buildings are constructed in a way to trap all of that mechanically-cooled air inside. That’s great for efficiency in daily life, but it hurts you in a heat emergency. Hopefully society starts to improve building designs by incorporating “passive” cooling as a backup without hurting active cooling’s efficiency.

Want to survive like a pro? Learn how to find and treat water, even in the desert, with The Prepared’s online water course. Also includes lessons on recognizing and treating dehydration.

Hydrating solves so many problems

Urine isn’t clear? Hydrate. Feel bad or injured? Hydrate. Not thirsty? Hydrate anyway.

It’s amazing how drinking water both prevents and solves many survival problems. But the majority of people don’t drink enough in their daily life — and during an emergency, people tend to drink less because of stress, limited resources, or just being distracted by what else is happening.

There are specific symptoms for dehydration, such as fatigue, dizziness, and confusion — but it essentially boils down to “you feel bad and the brain don’t work good.”

You may hear that caffeinated drinks dehydrate you, but that isn’t backed up by science.

Switchel or haymaker’s punch is a traditional electrolyte drink enjoyed by farmers scything hay in the summer heat. Here is a recipe from David Tresemer and Peter Vido’s The Scythe Book:

- 1 cup maple syrup, honey, or brown sugar

- 1 cup apple cider vinegar

- ½ cup light molasses

- 1 tablespoon ground sugar

- 1 quart cold water

- Combine and stir well

It’s technically possible to overdo hydration, leading to a condition called hyponatremia. The water itself doesn’t hurt you. But as you lose salts/electrolytes through sweating, combined with drinking a lot, the ratio of salts to water inside your body gets out of whack, starving cells of their needed nutrients. This is why sports drinks are more than just water.

The fix is simple: If you feel bad, but you know you’ve been drinking enough water (eg. your urine is clear), then simply eat something to rebalance the nutrients. Salty or sugary is preferred.

Infants, elderly, and the sick or disabled are at higher risk

It’s hard to know when someone is dehydrated (or worse) if they can’t communicate. An infant or catatonic grandparent can’t tell you they’re feeling bad, for example.

For children, pay attention to changes in their potty patterns. The lack of wet diapers is a clear sign. Another sign is when the child cries (or would normally cry in that situation) but there are no tears. You might also notice darker “sunken” eyes.

Elderly bodies aren’t as efficient at regulating temperature and require extra precaution. When a massive heat dome strikes, most of the fatalities are in the elderly population.

Another example is that people with spinal cord injuries (such as someone in a wheelchair) can have a hard time regulating their internal body temperature. In extreme cases, the damage to their body meant they can’t sweat anymore.

Heatstroke

If you see these signs, you need to take it seriously and immediately try to cool down:

- Throbbing headache

- Dizziness and light-headedness

- Lack of sweating despite the heat

- Red, hot, and dry skin

- Muscle weakness or cramps

- Nausea and vomiting

- Rapid heartbeat, which may be either strong or weak

- Rapid, shallow breathing

- Behavioral changes such as confusion, disorientation, or staggering

- Seizures

- Unconsciousness

Someone who experiences heatstroke will be more vulnerable in the near term after recovery. So be more cautious even when the person seems to have recovered.

How to dress for hot weather

You have three main goals:

- Block UV rays from the sun

- Wick sweat away from your body

- Maximize airflow

Stripping off clothing, such as going shirtless, is a great way to get a tan but a bad way to cool down when you’re still exposed to the heat. When you’re shirtless, for example, the sweat just stays on your skin.

You’ll get some cooling as the sweat evaporates — which is the whole purpose of sweating) — but if you can wick that sweat into clothing layers, it creates more surface area for evaporative cooling. And that now-colder air can be trapped in the protected gap between the fabric and skin, rather than that cooler air immediately leaving your personal bubble when shirtless.

General tips:

- Loose, light, breathable, airy clothing.

- Lighter colors reflect more light/heat than darker colors.

- Create your own shade and block the top of your head with hats, visors, etc. A typical hat that covers your head should have vents to let hot air move away from your scalp.

- Cotton is normally a fabric preppers avoid (“cotton kills”), but hot weather is one of the few places it can perform well.

- Layers can help. It seems counterintuitive, but why do you think Middle Easterners wear layers? The outer layers can help trap cooling wind, for example.

- Airy shoes like Crocs or sandals.

- If you’re not moving much, skip the socks. (If you are moving, use socks but rotate often to keep them and your precious feet dry.)

Survive heat waves at community cooling centers

A growing number of governments and charities provide “cooling centers” open to the public during heat waves. It might be a conference hall where they bring in industrial-strength AC units, free water, fans, and so on.

These centers often make the difference between life and death for disadvantaged and at-risk people, or simply those who have no AC at home.

Check Google, Twitter, and/or Facebook for your area to find open centers.

Shut up and breathe through your nose

As we’ve all learned from the COVID-19 pandemic, you spew moisture out of your mouth when you talk or sing. Pretty much any time you open your mouth, you are losing precious moisture. Mouth breathers lose 42 percent more moisture than nose breathers.

This concept was illustrated in Frank Herbert’s God Emperor of Dune, in which the half-man half-worm who rules the universe (long story) tricks a character into severe dehydration by luring her into talking while they stroll through the desert:

“Guard every breath for it carries the warmth and moisture of your life,” he said.

He had known they would be three more days on the erg and three more nights beyond that before they reached water. Now, it was the fifth morning from the Little Citadel’s tower. They had entered shallow drifts of sand during the night-not dunes, but dunes could be glimpsed ahead of them and even the remnants of Habbanya Ridge were a thin, broken line in the distance if you knew where to look. Now, Siona took down the mouth flap of her stillsuit only to speak clearly. And she spoke through black and bleeding lips.

Take a cue from Siona Atreides and keep your mouth flap shut.

If you do need to talk or breathe through your mouth, use a bandana or similar covering over your mouth to trap the outgoing moisture.

Place cool objects around the neck, armpits, and groin

Imagine you find someone passed out from a heat stroke. You happen to have ice packs available (or anything similar, such as a cold rock or drink bottle).

It matters where you put those ice packs. When someone is overheated, you are worried about their core temperature, not their skin temperature. It does them no good to get cooler skin while their insides are cooking — and the internal heat will undo any temporary positive changes you made at the surface.

The most effective way to use cold objects to lower body temperature is by placing them as close to the core organs as possible. The groin, armpits, and neck are better than just laying the ice packs on the chest, tummy, back, or shoulders because those areas tend to have a lot more insulating meat and bone between the skin and organs.

And those areas have major veins running near the skin, so you can cool the blood that then runs into the core. Some people will hold cold objects over the main veins on the ‘underside’ of their wrist, where a nurse might take your pulse. That can help, but it’s not as effective as the spots closer to the core.

You might think “I’ve heard people lose most of their body heat through their head, so in reverse, it would make sense to put ice around their head!” But that’s based on a common survival myth. There’s nothing special about the head that makes it a better heat conductor — it’s that people don’t cover their head as much as they do their body during the winter, so it’s where heat naturally escapes. So the head is not a biological shortcut to cool down the core organs.

Turn up the thermostat to acclimate for warmer temperatures

It’s obviously tempting to make the AC as cold as possible. Yet it’s overall a better strategy to get your body used to higher temperatures in situations where you might lose that AC, such as a rolling brownout/blackout due to the grid being overloaded or needing to evacuate from home.

Maybe you’ve experienced this when going on a tropical vacation. You’re sweating bullets the first few days. But then your body acclimates, becoming more used to the environment.

So try to keep your thermostat around 74-76°F (23-24°C) during the day / peak electrical grid hours. If things get worse, it will be much less of an uncomfortable shock to your body.

You’ll also do your part to “flatten the curve” and prevent the grid from failing — after all, you’d rather have some AC at 75°F than no AC at all. You’ll also save money on your electrical bill, since it takes a lot more juice to cool even just a few degrees more to 68-72°F, and per-hour electricity prices surge during those peak overload times.

If you don’t have AC, focus on letting air in while blocking the sun

Solar radiation through your windows can produce as much heat as several hundred kilowatts of electricity. So keep your windows covered with curtains or drapes.

If you have horizontal slat blinds that can close in two directions, close them in such a way that the sunlight doesn’t sneak through. The interior edge of the slat should be facing towards your ceiling.

Thermal blackout curtains are excellent for this and aren’t very expensive. A growing trend is to add a blackout layer in combo with the normal daily-life curtains/drapes on windows that get strong sunlight. That way you have adjustable ‘levels’ of protection.

People who live in consistently hot climates can add special UV film to their house windows. You can see outward just fine, but less of the heat makes its way indoors. This can be counterproductive during cold winters, though.

If you have an oddly shaped window or need to improvise something in the moment, get crafty with sheets, mylar emergency blankets, cardboard, and so on. One reader used a roll of kitchen aluminum foil as a reflective block in their windows during the 2021 Pacific Northwest heat dome, for example.

Even during peak heat, if there’s some natural breeze around, it’s usually worth opening up windows to allow that airflow — especially at night. You can block windows facing east in the morning, with west-facing windows open, and then swap as the sun moves towards the west.

Stay in the shade (or create some of your own)

The space under simple shade can be 10-15°F (5-8°C) cooler.

Even just standing in the sun for a few minutes can meaningfully raise your heart rate and core temperature. Pay attention to how quickly your heart rate increases the next time you stand out under a hot sun.

One of the reasons cities are hotter than the country is the lack of trees. Besides the shade they provide, trees will also ‘sweat’ and create evaporative cooling.

It’s worth creating your own shade if need be. That’s one of the many uses of a tarp, a core item in your go-bag. You can use a mylar emergency blanket as a tarp substitute, or better yet, use the reflective side of the mylar to bounce heat away. If you’re in a tent, try to optimize for airflow by removing the rain fly and placing it (or a tarp substitute) higher above the tent’s vented ceiling.

Leave the city and go toward altitude or ocean breezes

As the climate crisis gets worse, more citizens and local politicians are waking up to the fact that cities are heat ovens — especially cities with lots of stone/brick, dense buildings, or little greenery.

Even if it’s just for a day trip to get a break, it can be worth leaving the city if you have other areas nearby that will be cooler. Any rural area will be cooler than a city (assuming they’re being hit with the same weather), but the real cooling comes from gaining altitude or getting near open-water winds.

For example, someone in Salt Lake City can cool off by as much as 20 degrees when driving an hour up into the nearby mountains.

Hug the ground

People use a sleeping pad when camping in part because conduction sucks body heat away from you and into the ground, and the pad provides some insulation.

You can use the vice versa to your advantage — just like dogs, rabbits, and other animals will do when they overheat. Put as much of your body in contact with the ground as possible. This works particularly well in grassy or natural areas. Concrete, stone, or sand baking in the sun obviously won’t help you (but they can work at night!)

Get underground, or at least in your basement

If you’ve ever visited a cave or traditional wine cellar, you know things are naturally cooler underground. It can be 100°F outside but a cool 55°F just 10-20 feet inside a cave or underneath the surface.

If you’re at home and have a basement, that is usually the most naturally cool place you can shelter. During a heatwave, many families will ‘camp’ in their basement to stay away from the hotter upper floors.

Slow down and work or travel at night

It’s not a coincidence that parts of the world known to be constantly hot and humid, such as Southeast Asia and Latin America, have cultures where activity takes place at night while people stay inside during the day. Night markets, afternoon siestas, and even the general stereotypes that “southerners are lazier than northerners” come from these histories.

Be smart about when you expose yourself to heat and spend energy/water. If you don’t have to do something during peak heat, why would you?

If you have to be active during heat, slow down. Survival expert Cody Lundin says in 98.6 Degrees: The Art of Keeping Your Ass Alive that you should work at 60% capacity, which helps your body burn fat reserves instead of glucose and glycogen.

Use fans to get more air moving across skin

In the age of mechanical cooling, people have forgotten the art of fanning yourself, whether it’s with a magazine or a big banana leaf. Southern church ladies of old survived many long, fiery sermons in cramped, hot country churches by fanning themselves with (ideally large) hand fans often provided by the church itself. And on top of that, they were usually in their Sunday best, complete with a hat. Definitely not shorts.

Whether by hand or electrical, fanning helps because moving more air volume over your skin makes evaporative cooling work faster. Each “unit” of air can pick up and carry some heat away from you, so the more air units that touch your skin, the better.

Note that official recommendations from groups like OSHA are to avoid using fans when the ambient air temperature is over 95-100°F (35-38°C). That’s because the air moving across your skin is likely hotter than the skin itself, so the heat exchange doesn’t work in the direction you’d want it to.

Don’t cook indoors

In the opposite situation, such as your home losing heat during a winter storm, one of the tips is to cook indoors. Heating an oven while leaving the door cracked can really warm up a room.

So the vice versa is true, too. Stoves, cooktops, and other heat sources will pump hot air into your environment. Avoid it!

If you do need to cook, use an outdoor grill or take your portable camping stove (which many people have in their go-bag) to a shaded place outside. If you need to cook inside, do it outside of peak afternoon temperatures and try to use a fan to push hot air out the nearest window.

Take a dip (or a warm shower)

If you have access to water that’s cooler than the ambient air or your body temperature, swimming or soaking in that water can help lower your core body temp and provide much-needed mental relief.

UNBEARABLE HEAT: With temperatures soaring in the Pacific Northwest and British Columbia, this mama bear and her two cubs decided to cool off with a dip in someone’s backyard pool. https://t.co/dVXmhDesIO pic.twitter.com/xlN4GC3eGF

— ABC News (@ABC) June 30, 2021

A cold shower would help, right? Maybe not. When you take a cold shower, your body reacts in a way that reduces blood flow to the skin. That means the heat that would normally be carried to your skin and transferred away is now being kept inside the core. This is actually a good thing in cold emergencies, because your body is trying to protect its heat by shifting it internally where it’s protected from the cold air.

So, counterintuitively, a warmer-but-not-steaming shower can actually help you more in the long run (although it won’t feel great in the moment.)

Stay dry and clean

When you’re not specifically getting into water for direct cooling, you want to keep yourself dry. Hot, humid environments are a breeding ground for fungal infections like ringworm. This is why soldiers in hot environments constantly worry about their socks — wet socks equal trouble at a time you may need to rely on your feet to survive.

Try to maintain hygiene, even if it’s just with wet wipes.

We’re reluctant to recommend talcum powders due to their suspected links to certain types of cancer, but we’ve found that Gold Bond powder is pretty effective at wicking the sweat away from bodily crevices. Gold Bond also makes a cornstarch-based powder, but we learned the hard way that cornstarch can feed fungal infections.