We can thank the factory farming system for the plethora of food available on grocery store shelves, but its downsides are now well documented: animal cruelty, carbon emissions, contaminated food, and topsoil erosion, among others.

Unfortunately, there’s a number of anti-farming proposals that are well-intended — who doesn’t want to reduce animal abuse or cut down on gross animal factories? — but go about solving the problems in the wrong way. They’re similar to anti-2A laws that try to solve gun violence by focusing on the tools instead of the criminals who use them and the societal problems that drive them. Good intentions, wrong strategies.

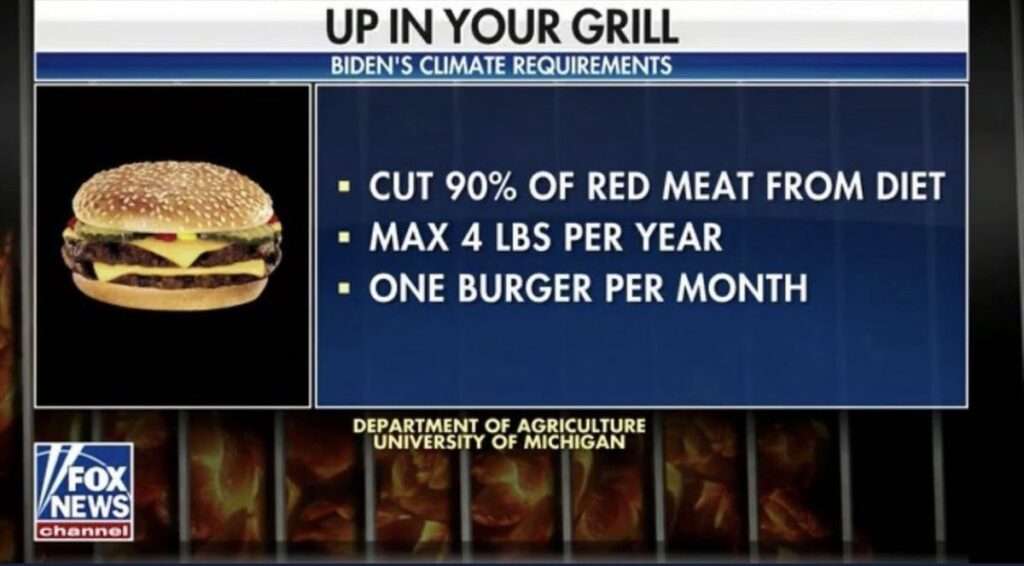

If you remember the recent drama where conservative media stuck its foot in its mouth by falsely claiming President Biden wanted to outlaw hamburgers… this is related. The reality is that the specifics of Biden’s plan are rather vague, simply saying “invest in sustainable agriculture and conservation.” His rural plan mentions helping farmers achieve net-zero emissions, which is again vague.

Some of these laws are still in the proposal stage, and it’s likely that this kind of pushback from the community will help soften some of the worst parts.

But we still thought it was worth sharing so you have a general idea of the kinds of ideas floating around government circles, especially since they seem to be picking up steam and could have huge impacts on your ability to grow or raise your own food — let alone how these changes would impact the overall food supply.

Oregon ballot initiative IP13

Activists in Oregon are gathering signatures to put initiative IP13 on the ballot, also known as the Abuse, Neglect, and Assault Exemption Modification and Improvement Act. The bill itself is short and rather confusing, because it deletes more law than it inserts. In effective, it removes “animal cruelty” exemptions for farmers and for animal husbandry with the intention of preventing “abuse, neglect, or sexual assault.”

The group behind IP13, End Animal Cruelty, explains its rationale:

No. This initiative would not ban the sale of meat, leather, or fur. It would, however, radically change how everyone treats animals, including those who work in animal agriculture. It would create a system in Oregon where farmers were no longer exempt from animal cruelty laws. It would require that animals be allowed to truly live a good life free from abuse, neglect, and sexual assault. After an animal lives a full life, and exits the world naturally and humanely, this initiative does not prohibit a farmer from processing and distributing their body for consumption.

In effect, the bill would make it so:

- Animals could not be slaughtered for meat. Rather, farmers would have to wait until the animal died of natural causes — at which point the meat is inedible anyway.

- Artificial insemination and castration of animals would be classified as sexual assault. Curiously, pets could still be spayed or neutered.

- Hunting and fishing would be effectively banned.

It would also likely have unexpected, but far-reaching consequences for transportation and other common animal husbandry practices.

Colorado PAUSE

Colorado’s Protect Animals from Unnecessary Suffering and Exploitation (PAUSE) initiative is very similar.

The chief difference in the PAUSE bill is that animals could be slaughtered, but only after reaching 25 percent of their natural lifespan. The initiative defines those lifespans as the following:

- Cattle: 20 years

- Chickens: 8 years

- Turkeys: 10 years

- Ducks: 6 years

- Pigs: 15 years

- Sheep: 15 years

- Rabbits: 6 years

How the Oregon and Colorado initiatives would hurt meat production and self sufficiency

If these initiatives get on their respective 2022 ballots, I think they both have a good chance of passing. After all, no one likes animal abuse, and to the uninitiated, many standard animal husbandry practices, like castration, seem horrifying. Let’s look at some of the possible ramifications of these initiatives.

Drastically reduced meat supply: Why are animals slaughtered at fairly young ages? Because that’s when the meat is the most tender. Meat chickens are usually slaughtered anywhere from 6 weeks to 5 months. Older chickens, usually laying hens, are best used for soup or chicken and dumplings, because the meat is too tough to roast or fry.

The same applies to pretty much any animal. USDA standards for grocery store beef grades (Prime, Choice, Select, and Standard) don’t allow for cattle over 42 months of age. Under PAUSE, cattle could not be slaughtered before the age of 5, which would push them into the lesser grades, only useful for ground meat or dog food. Forget juicy steaks raised in Colorado. Maybe you could marinate and pound the meat into edibility.

Also, the longer you keep an animal, the more likely it dies suddenly from natural causes or predator attack. It’s not hard to keep a flock of chickens alive for a couple of months, but keeping them going for two years is much tougher. Even the best farmers lose a few animals in that timeframe.

As for IP13 in Oregon, forget meat production, despite what the proponents say. No one harvests meat from a dead animal — unless they’re starving — because it spoils quickly. That’s why it’s essential to remove the guts from an animal quickly after slaughter, to drop the temperature of the meat and prevent growth of pathogens.

Dramatically higher meat costs: Lower supply of meat will naturally drive up costs, but the longer you keep an animal alive, the more you have to feed it, and feed isn’t free. Everyone who sells animals or meat for profit has to factor feed costs into their prices.

If I spend $20 a month to feed a flock of ten birds, that’s $2 per month per bird. If I buy chicks at $4 each, I’d have to charge $6 just to break even on eight-week-old meat birds. If, instead, I had to keep those birds for two years, I’d have to charge at least $52 per bird. And again, you won’t be making fried chicken with these birds, and I’ll have a lot less to sell due to flock losses.

Injuries to animals and people: There are three reasons farmers castrate male animals:

- Uncastrated males are aggressive and often attack each other, the females, and people

- The meat from uncastrated males is full of hormones that can taint the meat

- To prevent unplanned pregnancies

But for the small farmer in particular, injuries are perhaps the greatest concern. Imagine a small homestead having to manage a charging bull. And they would have to if artificial insemination was illegal because there would be no other way to produce calves or get milk. Artificial insemination is safer for the farmers, safer for the cows and heifers, and allows ranchers to select the best genetics.

More: Homesteading misconceptions: Why having goats is harder than you may have heard

I don’t raise cattle, only chickens, but roosters are bad enough. I’ve received some vicious pecks from roosters and they can do a great deal of damage to hens during mounting. I’ve had to cull a few for my safety and the safety of my flock. I can’t imagine the nightmare of an entire herd of raging bulls I couldn’t cull for five years.

Animal deaths during childbirth: Something that stood out to me in the PAUSE legislation:

SEXUAL ACT WITH AN ANIMAL ALSO INCLUDES ANY INTRUSION OR PENETRATION, HOWEVER SLIGHT, WITH AN OBJECT OR PART OF A PERSON’S BODY INTO AN ANIMAL’S ANUS OR GENITALS.

Anyone who knows anything about cattle, or has even seen a movie about cattle ranching, knows that many cows need assistance when birthing. Iowa State University says “While 70 percent of cows will deliver without assistance, only about 50 percent of heifers [first-time mothers] will deliver without assistance.” By assistance, that usually means putting on gloves, reaching into the cow or heifer, and pulling out the calf.

If PAUSE went into effect, ranchers would often be faced with an excruciating decision: risk being charged with a felony and being put on a sexual offender list, or letting mother and baby die a horrible death.

FDA, cattle, and leafy greens

It’s probably not news to you that our food chain is tainted. It seems like every other week we’re hearing about a salmonella, E. coli, or listeria outbreak in the food chain. The FDA recently released a report on a fall 2020 E. coli outbreak, pinpointing cattle runoff as the cause that is raising eyebrows in insider circles.

The report states:

Considering this, we recommend that all growers be aware of and consider adjacent land use practices, especially as it relates to the presence of livestock, and the interface between farmland, rangeland and other agricultural areas, and conduct appropriate risk assessments and implement risk mitigation strategies, where appropriate. Increasing awareness around adjacent land use is one of the specific goals of the Leafy Greens Action Plan we released last March, which we’re also announcing is being updated today to include new activities for 2021.

In short: E. coli has been linked to cow manure and leafy green producers should foresee possible contamination from nearby cattle, even if the cattle isn’t on their land, and those producers are expected to mitigate such contamination. While the FDA does not oversee the cattle industry — that’s the realm of the USDA — this could lay the groundwork for ranchers to be held liable for E. coli outbreaks as well.

Michael Taylor, a lawyer who served as Deputy Commissioner for Foods and Veterinary Medicine at the FDA from 2010 to 2016, said:

This finding seems obvious and shouldn’t be surprising. The surprise, however, is that FDA used regulatory language to express its finding and spelled out the implications: farms covered by the FSMA produce safety rule “are required to implement science and risk-based preventive measures” to minimize the risk of serious illness or death from the E. coli hazard.

Marion Nestle, the retired Paulette Goddard professor of nutrition, food studies, and public health at New York University, asked, “But leafy green safety is overseen by FDA whereas everything having to do with food animals is overseen by USDA…The Big Question: Will—can—the FDA force cattle ranchers and leafy green growers to adhere to food safety precautionary measures?”

Bill Marler, an attorney who specializes in foodborne illness litigation, gave this advice to restaurants:

Relying on a contact between the restaurant and its leafy green supplier is now not enough. Given the FDA pronouncement, restaurants need to affirm that the product be grown in an area where the “adjacent land” is not a “reasonably foreseeable hazard.”

It’s uncertain where this FDA stance could lead. Taylor doesn’t think the FDA will try to enforce it except under extreme circumstances, but I could envision a time in which leafy green producers sue neighboring cattle ranches for economic damages, either from FDA action or restaurants refusing to buy from producers that exist near cattle ranches, which is more common than you think.

Not to mention that many organic growers use good old cow manure to fertilize crops.

Instead of threatening leafy green producers, it would make more sense to fight E. coli at the source, and there are many options that the industry has so far resisted:

- A 1998 Cornell study found that finishing cattle with hay instead of grain dramatically reduced E. coli levels. Undigested grain ferments in bovine stomachs, which fosters E. coli growth.

- Yet another Cornell study, from 2018, found that keeping water troughs topped off reduced E. coli levels for unknown reasons.

- The Government Accountability Office has identified several methods of reducing E. coli in cattle, including bacteriophages, vaccines, and sodium chlorate, but again, the industry has been resistant.

Cattle ranchers don’t worry about E. coli, because it doesn’t affect the cows much at all, just the people who eat undercooked meat or those afflicted by tainted manure. Hopefully, this nudge by the FDA encourages more ranches to mitigate E. coli rather than form government cattle execution squads.

Manure: industrial waste or soil saver?

On the other side of the planet, farmers are fighting a draft rule by Environmental Protection Agency Victoria that would classify manure as industrial waste.

Australian farmers were baffled by the rule, as manure has been a key fertilizer for the entire history of agriculture. Allan Bullen, a chicken farmer and representative of the Victorian Farmers Federation said: “Farmers have been utilising animal manure as a sustainable by-product of agriculture for decades. To lump them with increased green-tape is baffling.”

Indeed, as a (mostly) organic gardener, the fight against cow poop is baffling. One of the great overlooked collapse-level happenings is the widespread loss of topsoil. A recent Yale report stated that the United States Corn Belt has lost ⅓ of its topsoil: nearly 100 million acres of it, thanks to industrial farming practices. The Union of Concerned Scientists said:

If soil continues to erode at current rates, U.S. farmers could lose a half-inch of topsoil by 2035—more than eight times the amount of topsoil lost during the Dust Bowl. They could lose nearly three inches by 2100. Given that it takes a century or more for an inch of soil to form naturally, the United States will lose the equivalent of at least 300 years’ worth of soil by 2100 if today’s trends prevail.

Unless something is done, the world could be facing a famine the makes the Dust Bowl look like nothing. We need to not only stop the loss of topsoil, but replace what’s been lost, and the single best way to build up soil is the addition of organic matter like manure. We need to use all the poop we can get. And there’s evidence that animal-based regenerative farming practices can actually reduce carbon emissions.

You are reporting the comment """ by on