Book Review: “The Black Swan”, by Nassim Taleb

(image credit: “Black swan” by Emiliana Borruto is licensed under Creative Commons – CC BY 2.0 )

In “The Black Swan”, Nassim Taleb discusses probability and the impact of unlikely but extreme events. He argues that we have a hard time understanding impacts and probabilities that are very large or very small. That what we do not know can be much more meaningful than anything we do know. Taleb argues that most of the course of human history has been dominated by extreme, unexpected, improbable events. And that human society will become more so in the future.

Taleb argues that we would benefit from improving how we think about unlikely, impactful events, and offers several tips for doing this. In this review I will outline the book itself, and then collect and present a summary of tips.

### What is a Black Swan?

A Black Swan event has three properties:

- Unexpected. Nobody saw it coming.

- Impactful. Causes a big change.

- Explained after the fact. We look back and invent an explanation for it, even though we didn’t know it would happen.

Taleb lists the Internet, the laser, and the start of World War One as examples of Black Swan events. Black Swans can be either negative (like a sudden war) or positive (like discovering a new drug or invention – like penicillin).

Throughout his book, Taleb argues that history moves in large leaps and bounds, not small steps. Most of the big changes in human history come from Black Swans.

Taleb believes we should work to make our lives and society more robust to Black Swans. Understand them better. Become less surprised by them. And be more ready, so we aren’t as impacted. “The surprising part is not our bad errors, or even how bad they are, but that we are not aware of them”.

### Mediocristan and Extremistan

Taleb distinguishes between two types of random probability and events – “mild” randomness with slight variations vs “wild” randomness with extremely impactful events. He calls these “Mediocristan” and “Extremistan”.

In Mediocristan – all of the events and data are about average. No single event or person greatly changes the total.

- Imagine gathering 1,000 people into a stadium, and comparing their weight. Even if you have one person with a very small weight (perhaps a baby) or a very large weight (the heaviest possible human) – they will not make up much of the total weight in the entire stadium.

- Examples of data or events in Mediocristan: height, weight, calorie consumption, income for a baker; gambling profits in a casino; car accidents, mortality rates.

In Extremistan you have a collection of “dwarfs” and “giants”. Some data points or events can be very small, and others hugely, massively out of scale, taking up most of the data.

- Imagine gathering 1,000 people into a stadium, and comparing their net worth. The numbers could vary much more than weight. If you happen to get Bill Gates in the stadium, he becomes worth 99.99% of the total data. None of the rest really matters.

- You would never see a human who weighed several thousand tons.

- Examples of data or events in Extremistan: wealth; income; book sales per author; name recognition as a “celebrity”; number of hits in Google; populations of cities; numbers of speakers per language; damage caused by earthquakes; deaths in a war; sizes of planets; sizes of companies; stock ownership; commodity prices; inflation rates; economic data.

One of Taleb’s central points is: mathematical models based on the Bell Curve can help a lot when explaining events or data in Mediocristan. But they do not work at all when dealing with complicated events or data in Extremistan.

- Mediocristan usually involves ‘biological’ data – physical measurements, or things present in the real world, where physical limits prevent them from getting out of hand.

- In Extremistan, we can never be sure of the data. Because one single person, point, or observation could suddenly dwarf the rest (imagine: measuring the net worth of everyone else, and then suddenly discovering Bill Gates).

- One measurement could suddenly invalidate all of our previous conclusions. So we need to proceed much more cautiously.

When measuring events or taking action in Extremistan, it is often the cumulative impact that is important. It doesn’t only matter if you were right or wrong; it matters *how* correct or incorrect you are. Being “right” about a danger causing one death, vs being “wrong” about a danger that causes 10 million deaths are quite different. We tend to “focus on the grass and miss the trees”.

The goal is to “be less surprised”, or “avoid being a sucker” about crazy, wild events that impact us.

### Part 1: Where and Why Brains Fail

Human brains are just not great at understanding some parts of the world. Especially risk and probability with very large or very small numbers.

Internal brain problems:

- 1) Narrative bias: Human brains love to invent and create stories, even and especially when no story or pattern exists.

- We do this unconsciously all of the time

- It takes mental effort to *not* create a story, or to *not* form an opinion

- Thus, humans can look at any set of totally unrelated data and *invent* a story about them.

- We think this helps us to understand the world better, but we are often wrong.

See “Thinking Fast and Slow”, by Daniel Kahneman.We have a “System 1” part of our brain – fast, intuitive, emotional, “gut feeling”.We have a “System 2” part of our brain – slower, more logical, critical thinking.It takes active effort and energy to do System 2 thinking. So it is harder.

- 2) Confirmation bias: We cherry-pick examples and data that support our story, and ignore evidence that goes against it.

- We also do this when predicting the future – we ignore times when we were wrong and only count the times we were right.

- It may only take one counter-example to prove an assumption is incorrect, so it may be faster and easier to disprove an idea.

Other thinking problems:

- 3) Silent evidence, a.k.a. Survivorship bias. It’s hard to keep in mind all of the data that we *don’t* see. For any problem or group of people, there may be a much larger group that we don’t know about, and don’t have evidence for.

- For example: There was an ancient civilization called the Phoenecians. They wrote on papyrus, which does not last long. Their papyrus writings rotted and decayed. So we didn’t have a record of much of their writing. It was easy to assume they did not write at all. Until we discovered their writing on other materials.

- For every person that “prayed to be saved” and survived, there are many that prayed but died. Only the people who made it are able to tell their stories.

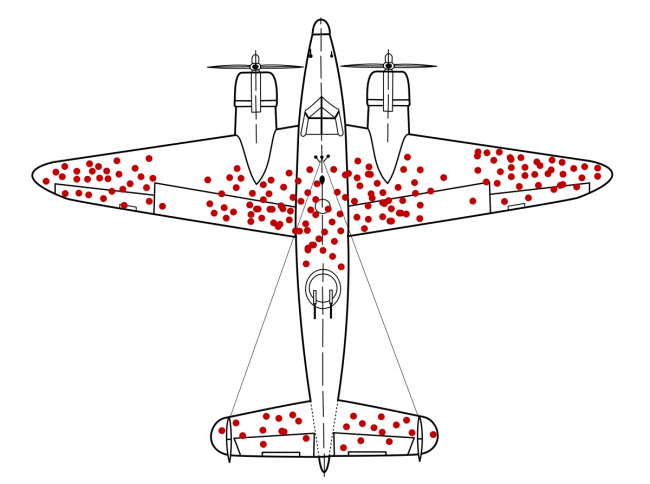

- In World War II, the US military was trying to figure out how to protect more planes from getting shot down. They initially wanted to add armor to the locations with the most bullet holes. But Abraham Wald figured out: every place with a bullet hole was a location where the plane could sustain a hit, *and still survive*. He advocated the opposite – adding armor to the locations with *no* bullet holes. Because no planes that were shot in those locations made it back.

[ Image: Bullet hole damage in WWII airplanes. Add armor to where there are *no* bullet holes, to increase survivability. Image By Martin Grandjean (vector), McGeddon (picture), Cameron Moll (concept) – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0 ]

Ignoring “silent evidence” causes us to massively underestimate or mis-understand the real situation and real risk or probability, because we don’t know the whole story.We have to continually be careful to not assume we really understand how the world works, and make dangerous assumptions.

- 4) The Ludic Fallacy: We may think we understand the world, but often we don’t. Real life is messier, stranger, and more complicated than we learn in the classroom or in constrained environments.

- You have to be open to crazy wild events that are “against the rules”. e.g. someone pulling a gun in a martial arts tournament.

- This is high-level “thinking outside the box”

- Taleb calls it “a-Platonic” thinking – not trying to stuff reality into tidy-but-incorrect categories

- Thinking we understand reality when we do not is what causes many Black Swan events, and is dangerous.

An example of the world being more complex than we think: A casino has a reputation for being a place of gambling and chance. But casinos actually have very strict controls on the size of bets you can place, the possible payouts, watching for people cheating, etc. It is a controlled environment. The casino will never pay out 100 billion times your bet, or change the rules of the game mid-game. But real life might do something similar.

By contrast – One casino’s biggest risks and losses came from sources entirely outside of the expected:

- A tiger attacked their star performer (Roy Horn of Seigfried & Roy). They were not insured for such an event, as they did not consider it a possibility. This ended their profitable best act.

- A disgruntled worker tried to dynamite the building.

- An employee had not been submitting the correct IRS tax forms, for multiple years. They simply put them into a drawer under their desk. The casino had to pay large amounts of penalties and back fees for not filing its taxes. It risked losing its license entirely and going out of business.

- A kidnapping attempt against the business owner’s daughter.

None of these risks or events were inside the casino’s business model or model of risk. They were entirely “outside the box”, and unexpected. Their cost was far greater than any on-model or expected risks or costs.

### Part 2: We Can’t Predict

Taleb spends several chapters showing how humans are bad at predicting. We can’t know the future and everybody gets it wrong.

- We fall victim to tunnel vision – ignoring possibilities outside of what we think will happen.

- We overestimate what we know, and underestimate uncertainty.

- The more information you give someone, the more they try to interpret, and the more hypotheses they will form along the way. We see random noise and mistake it for information.

- Our ideas are “sticky” – once we form a theory, we are not likely to change our minds.

- So delaying developing your theories makes you better off

- Developing an opinion based on weak evidence makes it more difficult to change

- “Reading a summary magazine once a week is better for you than listening to the news every hour”. The longer interval lets you filter the info a bit.

- Small errors in measurement or a model can lead to drastically different outcomes

- It doesn’t matter how often you are right; what’s important is your cumulative error number

- E.g. one big event can throw you way off

- Or missing one prediction

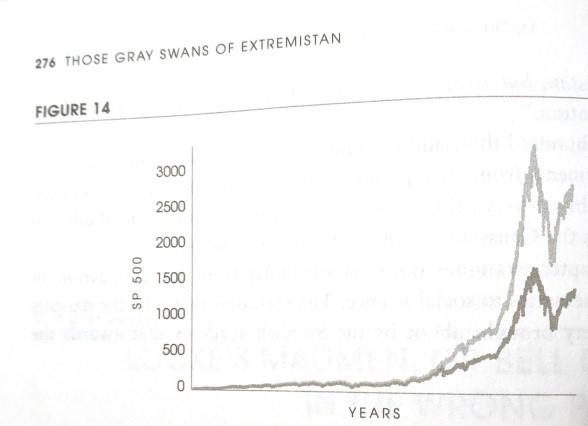

One example – for the entire stock market, over a period of 50 years – fully half of the total value of all stocks was created during only ten days. Out of a period of 50 years. Using current economics models and claims, these types of events should be nearly impossible. Yet here they are. Taleb uses this as an example disproving the claim of Bell Curve economic models and disproving economists’ ability to predict.

Taleb discusses “Retrospective Distortion”: History seems more clear and organized when we look back than it actually was for people going through it at the time.

### Part 3 and 4 – Technical Details

Parts 3 and 4 delve into technical details on how exactly many so-called “experts” are wrong, and advice on how to minimize damage from Black Swans.

- Taleb argues that the world is moving more into Extremistan over time. As technology and society become more complex, it is even more difficult to predict.

- The world is more complicated than many so-called “experts” and economists believe or tell you.

- The Bell Curve doesn’t actually work for most models; it can only be used to predict normal, boring events and data in Mediocristan. For any events in Extremistan – that includes most societal, cultural, and world events or data – the Bell Curve is a lie and *does not work at all*. This is a central point that Taleb emphasizes repeatedly.

By assuming the world is more complex than we realize by default, we can improve some events – “Turn Black Swans into Grey”. We are less surprised if we remain open to wild, impactful, unexpected events.

### What To Do About It

There are many interesting perspectives and advice that can be taken from the book. The most relevant areas are Chapter 13, “What to do if you cannot predict”; and Appendix 6 and 7 on The Fourth Quadrant – how to think about different types of risk, and mitigate them.

1. Look for counter-examples to check if you’re wrong

Because of confirmation bias, and because events in Extremistan can appear to be stable and normal for long periods, it is easy to find examples that reinforce any claim. That doesn’t mean we are right. If you have lunch with someone for an hour, and they don’t murder anyone for the entire hour, that doesn’t guarantee they are not a murderer.

It is faster and more effective to look for counter-examples that prove we are *wrong*. Ask “if this were not true, what would that look like?”.

2. Ask “Where did I get lucky?”

Examine past events. When you prepare a retrospective or After Action Report, ask “where did I get lucky?”. What events just happened to go well? From that list, what could you improve for next time, to improve your odds?

You see this in post mortems from organizations like the Google Site Reliability Engineering (SRE) team. They ask: “What went well? What needs to be improved? And where did we get lucky?”.

By considering events where we got lucky but it could have been worse, we can improve our robustness and preparations for next time.

3. Consider the consequences, or outcomes, and prepare for those

> “I don’t know the odds of an earthquake, but I can imagine how San Francisco (or any other place) might be affected by one”

The odds of some event may be unknowable, and no amount of modeling could figure it out. But I can guess pretty well how an earthquake or other event might *affect* me and my surroundings. And I can take steps to prepare for *that*.

If you lose power or water to your home, you don’t care as much about what caused it. You care more about how you can deal with it, and prevent it or make it easier.

Taleb’s advice is to focus on the *consequences* of some outcomes, and take steps to be ready for them. If we prepare for e.g. an earthquake, epidemic, financial crash, or other event, then it doesn’t matter so much about the odds of it happening; we can be ready regardless. “Rank beliefs by the harm they might cause”. “Invest in preparedness, not prediction”.

This matches advice from security expert Bruce Schneier, who advocates investing in intelligence gathering and emergency response:

> “Large-scale terrorist attacks and natural disasters differ in cause, but they’re very similar in aftermath.”

> The problem is that we can’t guess correctly. “Fund security that doesn’t rely on guessing”.

This leads to advice like:

- Keep an emergency fund, to help you deal with outcomes, whatever they are.

- Buy insurance to cover and mitigate your losses for bad outcomes.

4. Cover your basics; keep an open mind

We can’t know what the future holds. But if you allow for the possibility of unexpected, impactful events, you won’t be as surprised if or when they happen. By keeping an open mind about the possibility, you’re already better prepared. By covering our basics; accepting that we might be wrong; and having flexible preparations; we can adapt to events as needed.

5. Beware people selling you a solution

>“Avoid taking advice from someone unless they have a penalty for bad advice”.

Human brains have a harder time with ‘negative’ advice about what *not* to do. It is easier for us to look for or invent a solution. This is exploited by many frauds and scams – trying to sell you a solution that won’t actually work. Choosing to do nothing is itself a valid action and choice. “Don’t just do something – sit there!”.

Other Tips

- Consume less media and news.

- Lowers anxiety

- Avoids anchoring our thoughts to random data, which may cause worse decisions

- Do not listen to economic forecasters or predictors in social science.

- Don’t go deeply into debt.

- Don’t overspecialize. Learn some skills and/or have a job that can be transferrable or used for more than one type of work.

- Avoid optimization. Learn to love redundancy.

- The knowledge we get from tinkering and experimenting is better than just thinking and reasoning.

The Barbell Strategy: Be both hyper-conservative and hyper-aggressive, with different things, at the same time.

Taleb discusses his days as a financial stock trader. Since we can’t know whether anything is “risky” or not, it is impossible to build a portfolio that is “medium risk”. He suggests: Put 80-90% of your investments into ‘likely safe’ vehicles, such as bonds or Treasury Bills; put the rest into extremely speculative bets – such as Venture Capital investments in research & development, or startups. This limits your maximum losses while gaining you exposure to potentially lucky, positive outcomes.

Note: This is *not* financial advice. Please don’t make large adjustments to your personal finances based on a book summary you read on the internet.

### Positive Black Swans

Black Swan events are unexpected, and impactful. But they can be both positive and negative. Positive Black Swan events include discovering a new, beneficial medicine, or inventions such as the laser and the Internet.

Taleb’s Tips For Finding + Benefiting From Positive Black Swans

- Live in a city or hub of activity with an intermingling of people and ideas

- Go to parties

- Strike up random conversations with people at parties

- Invest in as many things as you can

- Keep an open mind. Good fortune could come from anywhere.

- Seize any opportunity, or anything that looks like an opportunity.

- Maximize your exposure to as many potential opportunities as you can. Put yourself into situations where favourable consequences are much larger than unfavourable ones.

You can decide how many of those you want to apply in your own life.

### Tips for a More Black Swan-Robust Community

- Avoid externalities. People who make decisions should have some stake in the outcome, or some consequences from the results of those decisions. No gambling with other people’s money.

- Build in some slack and redundancy. This is how complex systems survive.

- Start with small experiments. Test out small ideas first to see if they work or fail. Build and improve on the ones that work. If something will fail, finding out sooner is better than finding out later.

- Don’t take on large amounts of debt.

I have heavily adapted and synthesized this list from Taleb’s essay Ten Principles for a Black Swan-Robust Society. This essay is included at the end of the book.

In his essay, Taleb uses the term “society”. I am reframing a few of his ideas as: how could they apply to your local group or community?

Not many of us are world leaders. But some of us may have positions of leadership in our own community, or could step up to lead.

I believe the world is better if everyone is more prepared. If people all over the planet take one step or keep this in mind to work toward a more resilient planet, we all benefit.

-

Comments (3)

-